After Years of Ultra-Luxury Condo Development, Lenders Are Tightening the Purse Strings

By Adam Bonislawski April 6, 2016 12:00 pm

reprints

Last month, Gary Barnett, Extell Development Company’s president and founder, made headlines when he revealed he would be playing host to a group of Israeli bond investors concerned about the slowdown in New York City’s ultra-luxury condominium market.

Speaking to Bloomberg News, Mr. Barnett (who declined to comment for this story) professed himself unconcerned, noting the broad range of properties backing the bonds in question and the solid fundamentals underpinning Extell’s high-end projects. Nonetheless, the episode served to crystallize the growing caution with which investors and lenders are viewing New York’s super high-end condo market.

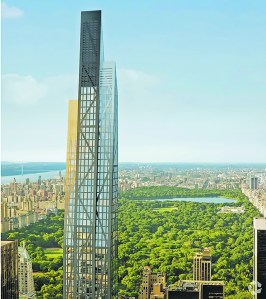

Mr. Barnett and Extell more or less kicked off the recent ultra-luxury trend with the construction of One57, the developer’s 1,005-foot, 92-unit super high-rise at 157 West 57th Street. The building was an early hit, selling half its units (totaling around $1 billion in sales) in its first six months on the market. By mid-2013, it had sold 70 percent of its inventory.

Three years later, however, the building has yet to sell out and now faces competition from additional ultra-luxury product like Harry Macklowe and CIM Group’s 432 Park Avenue, Zeckendorf Development’s 520 Park Avenue and Vornado Realty Trust’s 220 Central Park South. Meanwhile, buyer interest has also slackened with financial turmoil in markets like China and Russia potentially dampening foreign demand for super high-end Manhattan condos.

This, in turn, has led to a tightened financing environment for such developments, a number of industry experts told the Commercial Observer. While money is still available for the right projects, lenders and investors have become more circumspect with regard to ultra-luxury deals.

“Some large U.S. banks that are big commercial real estate lenders have become cautious to outright moratoriums in terms of construction lending for super high-end residential real estate in New York City,” said Brian Lancaster, an adjunct professor of finance at Columbia Business School and president of real estate consulting firm The Minot Group. “A combination of lower oil prices, which has diminished the ardor of Middle Eastern and Russian buyers, the slowdown in the Chinese economy, which has had negative effects in commodity countries such as Brazil, and stock market volatility, combined with a large amount of new construction, is causing prices to fall, making lenders more cautious.”

Indeed, according to an analysis published in May of last year by The Real Deal, a significant portion of the city’s current ultra-luxury projects, including the aforementioned 432 Park Avenue and 220 Central Park South as well as Hines’ 53W53 tower and Silverstein Properties’ 30 Park Place, had at that time not received any senior construction loans from a domestic bank.

This marks a shift from One57, which in 2011 received a $700 million construction loan from a syndicate led by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Foreign banks have in some cases stepped in to fill the gaps. For instance, in February 2014 Vornado secured a $600 million loan from Bank of China for construction of 220 Central Park South, which it recently expanded to $950 million. (Somewhat countering this overseas trend, Vornado also in November secured a $750 million loan facility for the development from lenders, including U.S. Bank and Wells Fargo.) That same year, Singapore’s United Overseas Bank originated an $860 million construction loan on Hines’ 53W53. The deal was later syndicated to a number of Asian banks, including Maybank, OCBC Bank and DBS Bank.

This move from a reliance on domestic to foreign banks is “a sure sign of a top” in the market, said Mr. Lancaster.

The next two years will be “interesting” ones for this market, said Marcus & Millichap’s Peter Von Der Ahe. “It is going to be difficult if you are trying to sell a $10 million, $15 million, or $20 million apartment right now.

“We have already seen that affect the type of financing people can get,” he said. “Banks have become more conservative with new development. They are looking at track record, experience, balance sheet, and they are looking at all these things more closely than they were 24 to 36 months ago.”

Lenders’ skittishness is “a function of the perceived risk of there being too much inventory and very high historical price points per foot, where you can’t really look backwards and substantiate the pace of absorption needed at the current price points,” said Peter D’Arcy, the New York City regional president of M&T Bank.

Ultra-luxury sales, in other words, can’t necessarily be projected using conventional models of condo sales.

“There seems to be a very large number of ultra-expensive units playing on a trend in globalization and money that is moving around the world trying to find a home,” Mr. D’Arcy said. “They are not necessarily relying on what you would think of as sustainable absorption trends that we can identify and know are longer lasting and count on. They are playing on different variables, and I think those are a lot riskier.

“There has definitely been a tightening in the traditional bank lending markets for condo finance.”

At the same time, “there is capital available,” noted Dustin Stolly, a managing director in the capital markets platform at JLL. “There is not nearly as much liquidity as there was a year or two ago, but there are projects that will and are continuing to get financed.”

In addition to foreign banks, non-bank lenders are an option for developers looking to finance super high-end product.

This latter market, Mr. Stolly said, has played a larger than usual role in the recent spate of ultra-luxury development. Institutions like Children’s Investment Fund have been among the major investors in high-end Manhattan development. Since 2011, the U.K.-based hedge fund has provided more than $2 billion in loans to New York City developers, including $400 million on 432 Park Avenue, $450 million on 520 Park Avenue and $660 million on 30 Park Place. The fund also provided $850 million to Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group for the construction of 15 Hudson Yards, which will house 285 condos and 106 rentals. (CIF declined to comment for this story.)

“The non-bank lending universe has played a far more prominent role in this development cycle than they have in any past cycles, and I think they will continue to do so,” Mr. Stolly said.

One significant advantage of going outside the traditional banking system for funds is that non-bank loans “typically carry no principle recourse,” he said. “Whereas traditional bank loans carry around 20 percent principle recourse.”

Equally important, he noted, is the convenience of dealing with non-bank lenders, particularly in the case of large deals like those required for ultra-luxury development.

“Nontraditional lenders have proven to be much easier to execute with and more nimble than your traditional bank financing,” Mr. Stolly said, noting that, for instance, a $500 million deal that could be financed by one or two non-bank lenders would likely require bringing a significantly larger number of banks to the table.

‘Nontraditional lenders have proven to be much easier to execute with and more nimble than your traditional bank financing.’—Dustin Stolly

“So that creates complexity in your negotiations,” he said. Developers pay a premium for this simplicity, he noted—typically around 200 to 400 basis points—but, Mr. Stolly said, “having [only] one or two lenders during the duration of a construction project is invaluable when you are going back to them monthly for construction draws.”

Going forward, new banking regulations that went into effect last year as part of the Basel III requirements could further limit the availability of traditional bank financing for ultra-luxury construction due to higher capital requirements from the lender.

While, as Mr. Stolly noted, there are reasons a developer might prefer a non-bank lender even in cases where traditional loans are available, Mr. D’Arcy suggested that the large role of non-bank financing in ultra-luxury development could also be a sign of weakness in the market.

“I don’t want to draw too strong a conclusion because there are numerous reasons why this is the case,” he said. “But when you see an asset class that is overwhelmingly getting its financing from non-banks, that could be a red flag.”

The takeaway, said Ayush Kapahi, partner at real estate capital advisory firm HKS Capital Partners, is that investment in ultra-luxury projects is “back where it should be, which is [looking] case by case at supply and demand of inventory in a specific area and an institution’s exposure in this market.”

While he said that investors had done “their due diligence” during the recent ultra-luxury run-up, a lack of visibility into the plans of other lenders and developers made it difficult to gauge the market.

“Obviously, as an institution you know what’s going on based on what you are working on and what you are financing, but you don’t necessarily know what the other institutions are doing and what the next developer is doing,” he said. “And all of a sudden if you are in position where you are entering 2016 and you find out that there are hundreds or thousands of units coming online because the 30 institutions that do construction loans out there have all given the green light, then that is something you don’t control. Nor do you have a real understanding of it until it is done, closed, financed, and the building is getting off the ground.”

The most straightforward way for ultra-luxury developers to secure financing in the current environment, Mr. Kapahi said, is upping the amount of money they have invested in the project.

“If there is a lot of capital at risk on the developer’s side, and the bank is comfortable at a certain basis that they believe they can exit and also that the developer can exit and make returns on, they will take the risk,” he said.

That said, Mr. Kapahi noted he was seeing little developer activity at this end of the market. “There haven’t been many new developers pursuing these types of projects in the last six months [with plans] to try to come online in the next two or three years.”