Can Tech Companies Convince Cities to Standardize Building Permits?

By Brady Dale July 15, 2015 5:30 pm

reprints

The first version of a new standard for data about building permits has been released today. “This data standard, called the Building and Land Development Specification, is now ready for broader adoption,” Mark Headd, a developer evangelist for Accela, told Commercial Observer during a recent phone call. Accela is a technology company focused on moving government processes, especially permitting, into the cloud, for greater efficiency and transparency. It is part of a consortium of tech companies including BuildFax, Buildingeye, Civic Insight, DR-i-VE Decisions, SiteCompli, Socrata and Zillow which introduced the new standard.

“This is an effort to make a standard way of representing this data, so that if you compare data across cities you can get insights that are meaningful,” Mr. Headd explained.

There is already a trend underway for cities to share data more openly. This is the next step, Mr. Headd contended. He knows something about city data. He was the first chief data officer for the City of Philadelphia, under Mayor Michael Nutter.

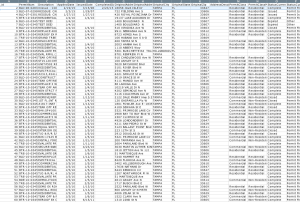

As the consortium of companies discovered, cities use slightly different terms or terms mean slightly different things within a given permitting process. This makes it harder than it should be to compare building activity across regions. Does a permit whose status is indicated as “under review” mean it’s under review by technical staff or by the relevant city board, or both?

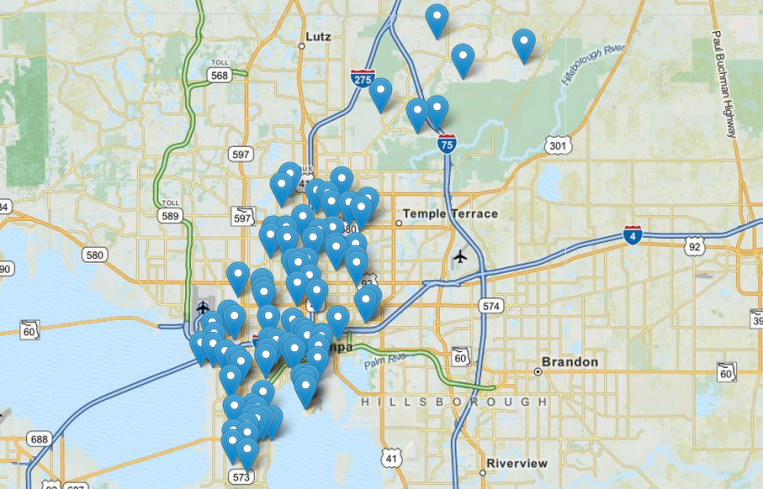

Is location data logged with postal addresses, some bespoke block-and-lot system or with longitude and latitude?

Is the life cycle of a permit attached to time? So, for example, is it possible to look back and see when a permit was submitted and when it was approved?

By standardizing practices and terms, the BLDS framework doesn’t change the rules, but it standardizes how information about projects governed by a given set of rules is expressed.

This should open up opportunities for real estate related startups to more easily scale across cities. If, for example, a company started to help developers pick spots for development, the rate of permits and the kind of permits in a given neighborhood could be valuable information to put in the mix. If such a company were to develop a secret sauce for New York City that incorporated such data, it would have to rewrite their code to incorporate a differently formatted data set if it wanted to expand to Chicago.

With standards, moving into a new city, at least in terms of incorporating permit data, would be vastly easier.

This reduction of data friction across municipalities is not unprecedented. When Google Maps began incorporating transit data, the demand from citizens to get their data into the system was too strong for communities to resist. Google, however, did not have the time or inclination to reverse engineer its maps to fit every community’s weird way of expressing information about its system, so it created the General Transit Feed Specification, a standardized way of expressing data about mass transit.

Just the opportunity to make transit times accessible in Google Maps has been enough to convince communities to reformat their data and publish it as live feeds. This has had the added benefit of adding a slew of new startups built on this data.

If the BDFS becomes widely adopted, we can likely look forward to the same effect on real estate data.

“When cities format their data and make it more accessible to the public, everybody wins. Data formats streamline the process of finding and using valuable raw data,” Ashkán Zandieh, the founder of RE:Tech, a real estate and technology consultancy, told CO via email. “That means that civic apps can come from technologists with talent and drive, not just enterprise companies.”

Early adopter communities already publishing data using the format include San Diego County, California; the City of Alameda, Calif.; Deschutes County, Ore. and Bernalillo County, N. Mex., according to a release from Accela.

The consortium has launched a public Slack group for city and technology professionals that want to take part going forward. (A Slack group a big way for folks to talk as a group in tech land.)

The consortium has not yet tried to reach out to New York City about the standard, Mr. Headd said, adding, “A reasonable question from a city like New York is, ‘Is this ready?’ It is now. This is a mature standard.” A spokesman for the city’s Department of Buildings, which provides the public with real-time access to department data and information, said he wasn’t familiar with the standard.