“I like what Michael Stern is doing and I want to figure out how to build more projects non-union.”

“I like what Michael Stern is doing and I want to figure out how to build more projects non-union.”

That’s what developer Bruce Eichner told the crowd at the Bisnow Multifamily Summit in March, with a smirking Mr. Stern, the young founder of JDS Development, sitting a few seats away.

As Mr. Eichner continued to gush over Mr. Stern’s well-publicized contempt for union labor, a heckler from the Building and Construction Council butted in.

“Boo…wrong!” the man yelled from the crowd before laying into the developers on the stage. “What about the people who build this city?” he asked. “What about the people that live in this city, that make up the city?”

Mr. Stern looked on disinterestedly—arrogantly—from the stage, seemingly unfazed by the exchange between the angry union worker and his well-dressed colleagues.

Maybe he didn’t care because he’d heard it before. Or maybe he did care. Maybe he was masking the fact that he was secretly thrilled that the message he’d been sending for the past year or so was being received loud and clear. His fellow developers, like Mr. Eichner, like what they’re hearing. They’re defending him. And they are already thinking of ways to go around the unions in the future.

‘JDS and Michael Stern [are] out in public … saying, “I’m gonna break the mold and build this super-tall building non-union.”‘

—Gary LaBarbera

Maybe organized labor should be scared of Michael Stern. This is war. The unions understand that Mr. Stern is their Waterloo.

It’s no secret that Mr. Stern, a 35-year-old newcomer to the New York City real estate business, puffs out his chest and thumbs his nose at the unions. He’s been portrayed in the press for the past year as an anti-union pioneer who is standing up to inefficient union bullies and who could potentially change the union culture of construction projects in New York City. Mr. Stern was recently named one of Crain’s New York Business “40 Under 40.” In its brief profile of the young developer, the publication lauded Mr. Stern for “turning the construction industry on its head.”

“The Long Island native’s 60-foot-wide, more than quarter-mile-high Steinway Tower on West 57th Street is just the latest of his projects that observers said couldn’t be done—in this case because he is planning to use non-union labor on the complex job,” Crain’s enthused.

Another Crain’s article about Mr. Stern said he and his partners, “believe they can build the 80-story tower without union construction labor, which for decades has held a lock on erecting the very tallest skyscrapers.”

This Crain’s piece is just one of dozens of media accounts claiming Mr. Stern is using non-union labor for his 57th Street project. The implication being only non-union. The reality, however, is that Mr. Stern—by his own admission—is planning on using some union labor on the Steinway Tower. In an interview with Commercial Observer last month, he claimed he never planned to do his high-profile projects non-union. In the case of the Steinway Tower, he says the divide will likely be a 60/40 split in favor of non-union shops.

If you ask Gary LaBarbera, who represents more than 100,000 union workers as head of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, the tenuous suggestion of using only non-union labor for his lofty projects tells you everything you need to know about Michael Stern.

“The character of JDS and Michael Stern—they’re out in public … saying, ‘I’m gonna break the mold and build this super-tall building non-union,’ when in fact that’s not factually correct? I think that’s a good starting point [in understanding Mr. Stern]. When you start off telling a half-truth, it speaks to the character of the person or the organization,” he continued.

Mr. Stern maintains that he has never said that he is planning to complete these projects without union workers, and insists that he is not anti-union. To that point, you will be hard-pressed to find a direct quote from Mr. Stern saying that he planned to complete this project with no union labor. However, he’s done little to dispel the myth.

Mr. LaBarbera has been at war with Mr. Stern for the better part of the last year. He’s made it clear in the press and at job sites that he sees the developer as a greedy, inexperienced construction neophyte who cares more about his bottom line than he does the safety of the workers he hires to construct his high-profile projects.

“Where did this guy even come from?” Mr. LaBarbera asked. “He thinks he can just roll into town and that he’s going to flip the entire real estate business on its head, when the reality is that’s not even what he’s doing?”

“The real motivator here is greed,” he continued, explaining that the non-union rhetoric is little more than a publicity stunt to bring attention to his projects.

These days, Mr. Stern will be the first to tell you that he is not a pioneer in the city’s shift toward using non-union labor. Nothing he is doing in terms of with whom he contracts is a game changer for the New York City real estate business.

“Almost every major developer now is doing the bulk of their residential work non-union,” he said, pointing to Related’s Hudson Yards project and two Extell Development structures, one on 14th Street and another on Charlton Street in Soho.

An expert in New York City real estate, who asked to not be identified, agreed, telling Commercial Observer that, “the city has been shifting towards non-union for 20 years.”

What makes Mr. Stern’s projects different—and what makes him so scary to the unions—is the size and complexity of the jobs he’s trying to do with limited union involvement. Steinway Tower’s thin foundation, for one, will be particularly tricky. CO’s expert said that Mr. Stern’s plan to construct what will be one of the tallest, and thinnest, buildings in New York City without the unions would be impressive—“if he can actually pull it off”—something Mr. LaBarbera said he doesn’t think he can.

“I am not convinced he has the capability to build this non-union given the need for skilled workers on such a complex and high-end project,” Mr. LaBarbera said.

Just as Mr. Stern’s use of non-union labor is not unprecedented—or factual, for that matter—neither is a labor union raising a huff each time they’re passed over for lucrative construction jobs, and Mr. LaBarbera has been on the frontlines of battles with several other developers who have tried to go the non-union route.

In 2013, Mr. LaBarbera went after The Moinian Group for its frequent use of non-union labor. Last year, Alma Realty and Acadia Realty, among others, found themselves in the labor boss’ sights. The list of developers who draw the ire of Mr. LaBarbera for using non-union labor is long and growing.

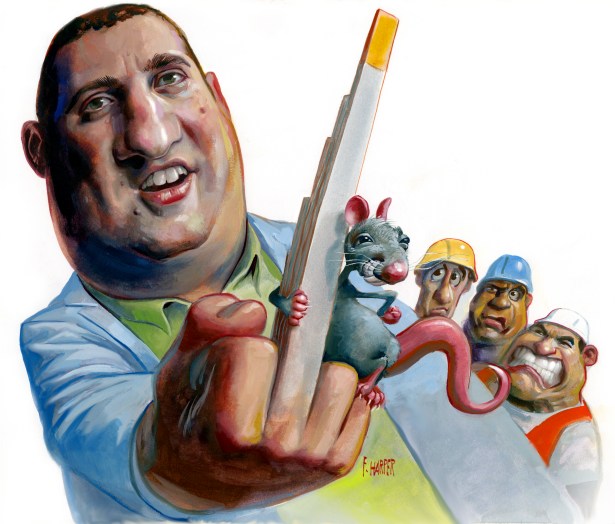

What makes Mr. Stern different? Every war needs a symbol. Think of the way the inflatable rat has emerged as a call to action for labor sympathizers. Michael Stern—an arriviste who splashed into Manhattan filled with bold pronouncements about disrupting the way buildings are erected (and the lives of those who erect them)—has emerged as a symbol of all that threatens the very existence of building trade unions.

Mr. Stern is not the only developer who uses mostly non-union labor. But it’s the crowing as much as the reality. As Mr. LaBarbera said, “Michael Stern has boasted of his use of non-union labor so [he] also has drawn more attention to the issue.”

If Mr. Stern is able to complete a large-scale, complex project like the Steinway Tower with limited union labor, it could send a message to other developers that they can, too.

Given the height of the structure, and the narrow foundation, construction is going to be complex, experts say. One noted, “every aspect of this job is going to be significantly more difficult because of how thin it’s going to be—if it’s ever actually built.”

“I think if they built it successfully, more developers doing projects of that size would have to take a look at going non-union,” Extell Development founder Gary Barnett recently told Crain’s.

Accordingly, to preserve the relevance of his union, Mr. LaBarbera is not making that easy.

|

‘The Department of Buildings is a self-funded agency through their violations—they are out there to improve safety but also to raise revenue.’ |

Like most large-scale development projects, Mr. Stern’s projects are not without safety incidents. What makes his projects different, according to Mr. LaBarbera, is the number of incidents—although, Mr. Stern’s projects often have fewer safety violations than union jobs of similar size.

Since Mr. Stern took ownership of the Steinway Tower property, there have been 34 complaints made to the New York City Department of Buildings about safety conditions at the worksite for a variety of concerns.

The violations at Steinway Tower have been for things like workers not latching their safety harnesses while working on scaffolding and failure to comply with fire codes. On another of Mr. Stern’s projects, at 626 First Avenue, a worker fell two floors when he stepped on a faulty floorboard. At the Steinway Tower site, three worker injuries were reported to the DOB in April alone—one worker cut his hand, another injured his ribs while using a drill and a third suffered an eye injury while installing circuit breakers.

Additionally, neighbors in an adjacent apartment building reported damage to their building caused by construction at the Steinway Tower. In March, those neighbors reported that Mr. Stern’s project had caused cracks in the walls of their building. Others reported construction debris coming into their apartment that got so bad, a special ventilation system had to be installed to keep the dust out. Another reported that she had to move her 4-month-old child out of their apartment because of the dust, the constant vibrations and other noises coming from the construction site.

Mr. Stern strenuously denies that JDS is particularly haphazard about safety and places the blame for the complaints on activist unions and a scheming Department of Buildings. For perspective, there were 143 complaints made about 157 West 57th Street, a largely union job, which included a crane dangling from its rooftop after Hurricane Sandy. Many of the complaints about the Steinway Tower, Mr. Stern said, are the result of union workers who “sit in front of the jobsite and call 311 [to report potential violations] 100 times a day.

“I’m very proud of my safety record,” he said. “We’ve had a spectacularly good safety record and the unions can’t point you to data about our historic jobs that say otherwise. Have we had violations on jobsites? Sure. All construction sites have violations. The Department of Buildings is a self-funded agency through their violations—they are out there to improve safety but also to raise revenue.” Mr. Stern said JDS goes to great lengths to ensure that his contractors follow best practices when it comes to safety training, but sometimes things happen because the construction industry is “an inherently dangerous industry.”

Despite the inherent dangers of the construction industry, Mr. LaBarbera counters that there are ways to reduce risk, and it starts with hiring responsible contractors—something Mr. Stern often fails to do.

One of the contractors working on the Steinway Tower project is Parkside Construction, which has a long history of safety violations, among other issues.

In September of last year, 27-year-old Rodalfo Vasquez-Galian was crushed to death when a concrete slab fell on him as he was pouring the foundation of a project at 326 West 37th Street. The contractor: Parkside Construction.

“If you look at the contractors in both union and non-union … most of the big-union concrete contractors are run by a bunch of guys who sat in jail for years. They’re mafia-affiliated. Long, lengthy criminal records, safety issues, etc.,” Mr. Stern said.

Speaking of mafia-affiliated concrete contractors, the sub-contractor who was doing the concrete work for Parkside Construction on the West 37th Street project was Carmine Della Cava, a former member of the Genovese crime family who was convicted of bid-rigging in the mid-1980s, according to published reports.

“I’m not saying every contractor we hired had a perfect record, but if everybody wanted to hire a choir boy to do construction in New York City, there would be no construction in New York City,” Mr. Stern said.

The union has pounced on many of these issues and has launched a PR campaign against Mr. Stern, highlighting some of the more serious offenses, and has garnered the support of local politicians in the attack. Worth noting, there is considerable value for a politician to be in the good graces of large labor unions, as they represent hundreds of thousands of organized voters. With that understanding, politicians like City Councilman Cory Johnson and Public Advocate Letitia James each have come out publicly against Mr. Stern, noting safety issues on his jobsites.

“My biggest issue with the union argument on the safety issues is that it’s totally disingenuous and opportunistic,” Mr. Stern told CO. “When the unions have a major crane accident, like the one on 50th Street and Second Avenue that killed seven people a number years ago, followed a month later by an accident on 91st Street that killed two people, you didn’t see the non-union developers or contractors gleefully run to the media to brag about how unsafe the unions are.

“Being safe is not only the right thing to do, it’s good business. It’s good for the bottom line,” he continued.

Mr. Stern maintains that he is not an anti-union guy, which is why he is using union shops to do some of the more complex jobs on Steinway Tower.

“There are certain aspects of certain jobs that the unions are still more advanced than the non-union world, and frankly that gap is closing rapidly, but it hasn’t closed all the way yet,” he said.

He declined to say which aspects of the project will be completed by union workers, but things like ironwork, elevators and HVAC systems generally require more skilled labor—labor Mr. Stern concedes is often done better by union workers.

In other areas, Mr. Stern said, it simply doesn’t make financial sense to use union labor, for a variety of reasons.

“We’ve done union work in the past, we will do it in the future,” he said. “We’re not opposed to doing jobs with unions if it makes economic sense, but we have issues with the way unions function that create massive inefficiencies that are just not sustainable in a business environment.”

Some of those inefficiencies were outlined to CO by a New York City architect who deals with both union and non-union workers on a daily basis. He also asked to not be identified, but said in an email, “You could argue, fairly objectively, that union labor is better.” However, there are problems.

“There are a lot of rules about what they can do, when they can do it, how many breaks they get, blah blah blah. One time, I was on a job site and saw a guy stop cutting a piece of plywood, literally halfway through the cut, because his shift was over. It would have taken him about five minutes to finish. And another guy from a different trade needed that piece of wood for something else, and that second guy was working overtime, but couldn’t do his work because the first guy screwed him by not finishing,” he said.

Mr. Stern said instances like the one described by the architect are not conducive to running an efficient business, and if he can avoid those types of issues, and still get the job done properly, that’s what he’s going to do, regardless of what Mr. LaBarbera has to say about it.

“Unions have been slow to adapt to the current modern needs of the construction industry, which is why they’re losing so much ground,” he said. “And I understand that that’s frustrating for them, but they need to look in the mirror and realize that the reason they’re losing isn’t because of what guys like me are doing. They need to look at themselves and say, ‘What kind of changes can we make to adapt to not lose market share?’”

To that point, Mr. LaBarbera said he is in the process of revamping project labor agreements to get rid of some of the rules that lead to the inefficiencies of which Mr. Stern speaks.

The war between JDS and the unions is not likely to come to an end any time soon. Mr. Stern said the plans to move forward with Steinway Tower have not changed, and that he expects a crane to be on-site by early June. His plans to forgo Mr. LaBarbera’s union have not changed.

“[This] has nothing to do with me. It has nothing to do with safety issues. It’s simply because the union’s work rules are antiquated and needlessly drive up cost—and the unions need to adapt and take away their entrenched entitlements that needlessly make the bottom line harder for a developer to get over. And then they will get their market share back,” he said.

For his part, Mr. LaBarbera shows no sign of standing down, either. He recently held a rally at one of Mr. Stern’s job sites and has protestors camped out in front of Mr. Stern’s office almost every day—and he is using the union’s PR machine to make sure news of Mr. Stern’s alleged dirty deeds make headlines.

Mr. Stern, however, feels like he is little more than a “symbolic target” of union bullying.

“It’s me this time. It’s my turn,” he said. “Last year it was a different guy, and next year it will be somebody else.”

Update: This article was edited after publication to reflect the fact that Crain’s “40 Under 40” profile of Michael Stern did not explicitly say that construction of 111 West 57th Street would rely solely on non-union workers.