The MTA’s Capital Plan Remains Held at the Station as Major Funding Gap Grows

Delays affect projects big and small throughout the New York region

By Mark Hallum January 15, 2025 6:00 am

reprints

It was Christmas Eve 2024, and the New York State Legislature wasn’t in the giving mood.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority was asking lawmakers to approve its 2025-2029 capital plan — a spending blueprint $10 billion larger than the last one that seemed so outlandishly expensive back in 2019.

The $68.4 billion capital improvement plan, even with congestion pricing starting up in the new year, was still short by about $33 billion. And, no, there were no proposals of how to fill the gap between income and expenses.

But the legislature’s end-of-year rejection of the five-year capital plan, which technically began Jan. 1, means the MTA starts 2025 without the approval it needs to get rolling on contracts it could hypothetically sign off on considering at least half the funding for them is in place, MTA Chairman Janno Lieber said in a letter to Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins.

“To veto the plan because funding issues remain to be resolved creates an almost insurmountable Catch-22 scenario,” Lieber wrote in the letter. “The MTA is required by law to submit an approved plan prior to the very legislative session where funding issues related to that plan will be addressed.”

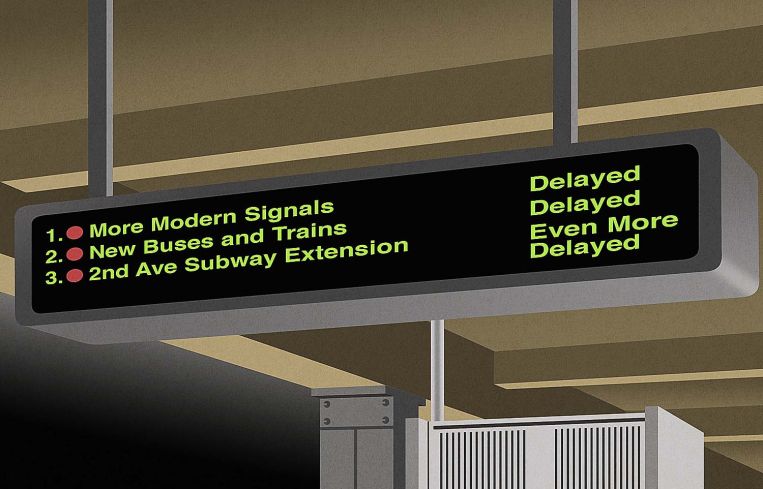

Lieber had hoped, as stated in the letter, that the legislature would reverse its course on the capital plan by Jan. 9. To drive home his point, Lieber rattled off a number of projects that will be delayed thanks to the legislature’s actions.

“Power upgrades at 47 substations and 16 circuit breaker houses, structural repairs on more than 10 lines, painting and repairing more than 20 miles of elevated structures, modernizing signals on the A line, replacing elevators or escalators at 13 stations, three station renewals, and ADA improvements at 17 stations,” Lieber catalogued in the letter, the last item a reference to the Americans with Disabilities Act.

During the MTA’s September board meeting, the capital plan was unanimously approved and included the assumption of $14 billion in grants from the federal government. Those grants likely will not get approved by federal officials in Washington without a capital plan in place from the state, according to the agency.

The plan will be re-evaluated during the next legislative session between now and June.

The $55 billion 2020-2024 capital plan was the largest of its kind, having been approved in late 2019 and including ambitious modernizations across the MTA systems. Much of that work is still underway after the COVID-19 pandemic stalled some projects, but the MTA’s list of fixes needed to keep the system in a state of good repair grew exponentially nonetheless.

“We’re moving 5 million people a day on subways and buses, and it’s a 100-year-old system,” Jamie Torres-Springer, president of MTA Construction and Development, told Commercial Observer. “What happens with infrastructure, real estate and physical facilities is that they tend to deteriorate, particularly if, historically, you haven’t invested in keeping them in a state of good repair. And, honestly, a lot of previous generations have not made some of those behind-the-curtain investments that don’t get a lot of public play, but are really important to keep running the service safely and reliably.”

Legislative approval would also allow the agency to raise about $10 billion through bonds. If unable to sell bonds, the MTA could now be forced to reallocate money that has already been earmarked to delayed items in the 2020-2024 capital plan, Lieber also stated in the letter.

“We are reviewing the letter,” Mike Murphy, spokesperson for the New York Senate’s Democratic majority, said in a statement. “But I think it is absurd to say this rejection will result in the delaying of projects when we all know there are projects from the last capital plan that haven’t even started yet. We look forward to continuing the conversation with all the stakeholders in order to advance a fully funded capital program that addresses the vital transportation needs of the MTA network, which are critical to the state’s and region’s economic well-being.”

While not ideal for the MTA, lawmakers aren’t totally out of line by vetoing the capital plan.

“It’s not surprising at all to see the legislature use their leverage here,” Rachael Fauss, senior policy advisor of watchdog group Reinvent Albany, said in an interview. “Technically speaking, when the [MTA’s] Capital Program Review Board looks at the MTA capital plan, having the funding identified is very important and part of their role – and it isn’t there. It’s not like the last capital plan, where the congestion pricing was teed up ahead of the capital plan being approved … This is a much bigger funding gap than we’ve seen before, because the plan is that much bigger.”

Generally speaking, a bigger, more ambitious plan is not always in the best interest of the public if improvements and expansions are prioritized above state of good repair investments, Fauss said. On the other hand, Fauss pointed to a September report from State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli’s office that the bare minimum needs of the MTA could range from $57.8 billion to $92.2 billion, with a midpoint of about $75 billion.

“We’ve always been, as a watchdog group, concerned that a capital plan weighs too heavily on expansion versus state of good repair,” Fauss continued. “No. 1 should always be to make sure things don’t fall apart and improve service reliability.”

This capital plan, giant as it is, is 90 percent focused on keeping the system in a state of good repair, according to Torres-Springer. He noted prices are higher these days for new rolling stock, such as the 270 new electric buses on the MTA’s shopping list, as well as the infrastructure upgrades and facility renovations meant to keep the system running to the expectations of New Yorkers. Those costs are equally as subject to the 30 percent inflation seen over the last five years as a bag of groceries.

The MTA, too, is eliminating some of its oldest train cars from its fleet, namely the 1980s-era cars with the orange and yellow toned seats, replacing them with 435 R211 cars that will have surveillance cameras and which cost about $1.27 billion. The plan is to deliver these by 2027.

Meanwhile, the MTA has already initiated procurement work for portions of the Second Avenue subway extension, a decades-old pipe dream for many, bringing improved subway service to East Harlem at 125th Street as well as diverting foot traffic from the 4, 5 and 6 trains.

The legislature’s rejection of the capital plan also puts into question the status of the Brooklyn-Queens light rail project known as the Interborough Express Connector, meant to channel commuters along north-south routes between the two boroughs where they can access 17 subway lines and 51 bus routes.

The MTA still needs to fund modern signals on the A and C lines in Brooklyn and Queens, which is also in the 2025-2029 capital plan.

Putting off approval of the capital plan until later comes with a number of other challenges, especially considering all the legislative matters that hit a peak in the first and second quarters of any given year, as well as Trump re-entering the Oval Office, said Tiffany-Ann Taylor, vice president of the Regional Plan Association.

“I think that we’re also going to see, or at least maybe we’re starting to see, the state legislature getting ready for more of a skirmish as we start to approach budget season in the spring because the capital plan already has a deficit,” Taylor said in a Dec. 31 interview. “I think that this decision [by the legislature] is now setting the stage for MTA spending to be even more of a front-line conversation come the springtime.”

Obtaining federal grants and allowing the MTA to issue bonds before the Trump administration takes office Jan. 20 was considered one of the most critical steps for Lieber given that the Biden administration has historically been more infrastructure-friendly than the administration that came before it. (Biden also earned the nickname “Amtrak Joe” because of his love of trains.)

The Trump administration, after all, had let congestion pricing languish in bureaucratic limbo for a number of years until Joe Biden took office in 2021, finally granting federal approval for the state program to proceed. Regardless of the momentum behind congestion pricing during the Biden years, the program is only now getting underway.

At the very least, the new congestion pricing tolls will provide some independence from Washington.

“Hopefully, fingers crossed, congestion pricing will be actively running and we’ll understand what revenue is really coming in now that it’s $9 versus the $15 [originally proposed],” Taylor said of the toll for most motorists entering Manhattan’s core. “I think the legislature will have more information at their fingertips to figure out where the money is really coming from.”

Without the $15 billion in revenue from the tolls, New Yorkers could have faced another era like 2017’s “summer of hell” (then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s words). In fact, it was the transit meltdowns of that year that made a congestion pricing toll into Manhattan below 60th Street suddenly more palatable for legislators, government officials and transit advocates.

Previous proposals for a similar toll had fallen flat.

The MTA also plans to pick up on tasks that have been deferred over the years, such as adding elevators to at least 60 more subway stations, still making only about half of the 472 stops in the system compliant with the 1989 Americans with Disabilities Act. The new capital plan will also replace the old trains, which cause a high number of delays due to unreliability. The agency also proposed replacing over 70 miles of signals, mostly in parts of Brooklyn.

Soon after approving the 2020-2024 capital plan, the agency found itself in the heat of a different kind of battle entirely as COVID-19 sickened and killed transit workers and drove ridership to historic lows. Unbeknownst to officials at the time, congestion pricing was still five years from becoming a reality.

Fast forward to June 2024, more wrenches were thrown into the gears as Gov. Kathy Hochul put a last-minute pause on the initiation of congestion pricing, just days before the tolling cameras were set to be activated.

Rumors swirled that Hochul paused congestion pricing’s launch purely to help Democrats hold onto power in Washington, D.C. Eventually, the governor set a Jan. 5 date for the start of tolls that would cost the average motorist $9, a 40 percent discount from what MTA officials and their advisers, including from commercial real estate, had recommended.

The MTA tried its luck at adding another 25 percent to the $9 toll on “gridlock alert” days, but Hochul wasn’t having any of it, saying tat the entire reason she had reduced the price of admission into central Manhattan was to keep costs low for lower-income motorists.

“The legislature not approving the MTA plan only means it should be realigned to identifiable revenues until we have a better understanding of the sources of funds for the unfunded portion of the plan,” Mike Whyland, a spokesperson for the Assembly speaker’s office, said in a statement. “Currently, more than $30 billion of the MTA’s plan is fully financed, and the MTA can reasonably resubmit a plan to utilize expected federal dollars and other specified revenues, which would allow projects to begin or continue while additional revenue sources are identified. It is also vitally important for the federal government to step up and support the lifeblood of one of the most important economic drivers in the country.”

Mark Hallum can be reached at mhallum@commercialobserver.com.