Trump’s Open War With Jerome Powell Risks Damaging Commercial Real Estate

And a lot more — but by how much? ‘I’ve been amazed at how benign the markets have been to all this chaos.’

By Brian Pascus January 16, 2026 12:08 pm

reprints

President Donald J. Trump’s war with the central bank of the United States, and Jerome Powell in particular, ratcheted up several DEFCONs this week.

On Sunday night, Jan. 11, the Federal Reserve chairman released an extraordinary video, in which he recounted how Trump’s Department of Justice served him grand jury subpoenas and threatened a “criminal indictment” over his handling of a multibillion-dollar renovation to the Fed’s Eccles Building headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Powell did not mince words or back down, and pointed the finger directly at Trump, implying the accusations surrounding the ongoing building renovations were a cover for the president’s frustrations that the Federal Reserve has not responded to Trump’s repeated desires that the benchmark Federal Funds Rate be lowered quicker from the 22-year high of the 5.25 to 5.5 percent target it reached in mid-2023.

“The threat of criminal charges is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the president,” said Powell.

Today, the benchmark short-term interest rate stands between 3.5 percent and 3.75 percent after Powell lowered it three times in 2025 — yet clearly not low enough for Trump’s liking.

And, while many voices within the world of finance have avoided wading into political flights, the action set off immediate alarm bells.

“I think this is all about Trump not wanting to lose the midterms,” said Chad Carpenter, founder and CEO of Reven Capital. “What does he have to do to not lose the midterms? He needs to keep GDP up, keep employment and the stock market up, and bring costs down, and, right now, short-term interest rates are still relatively high.”

But the perception that the independence of the Federal Reserve is being meddled with poses a much greater risk than an isolated political spat between a central banker and the executive branch.

“An independent Fed is operating off a dual mandate set forward by Congress of price stability and full employment, and on this front, the executive branch is trying to come in and exert more influence over monetary policy,” explained Brian Bailey, who spent 14 years at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and is now a senior researcher at commercial real estate loan servicer Trimont. “From that standpoint, you don’t want undue political interference creating additional factors that influence their decisions.”

The negative reactions against Trump’s interference in Fed operations have been swift.

Several top Republican senators and Trump allies have voiced their displeasure; numerous former Fed chairs and Treasury secretaries over the past 30 years signed a statement criticizing the move; and the right-leaning Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote, “In the annals of political lawfare there’s dumb, and then there’s the criminal subpoena federal prosecutors delivered to Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell.”

However, across the commercial real estate spectrum, Trump does have his defenders.

“Everyone knows what’s been going on: Trump has wanted an easing of monetary policy, and, frankly, that’s good for commercial real estate,” said Glen Kunofsky, founder and CEO of Surmount, an investment firm. “On the political and criminal indictment side, my view is that anything that puts pressure on the Fed to lower rates is a good thing.”

Others in the industry criticized Powell’s record as Fed chair, which ironically began in 2018, when he was nominated by Trump during his first term, and continued through the 2020s after President Joe Biden kept him on to oversee the central bank coming out of the COVID pandemic.

“Did Powell do such a good job? Eleven interest rate hikes in 12 months doesn’t sound rational to me,” said Adelaide Polsinelli, a vice chair at Compass. “Look at the repercussions of Federal Reserve policies: They’ve devastated the housing market and gutted real estate. How can you argue the actions of someone in his position were intelligent, or were consistent with historical analysis?”

Under Powell’s watch, the Fed initiated the swiftest interest rate climb in 40 years, administered the painful medicine of quantitative tightening (whereby it reduced its $9 trillion balance sheet to less than $7 trillion, by selling short- and long-term U.S. bonds), and stood idly by as the 30-year rate on home mortgages shot up to its highest levels in two decades, mainly because of QT.

Powell follows all his immediate predecessors who held the big chair in taking the blame for periodic nosedives in the economy: Janet Yellen kept interest rates too low for too long in the late 2010s; Ben Bernanke arguably responded too late to the housing bust in 2007-2008; and Alan Greenspan had the dot.com bubble explode on his watch in the early 2000s.

“The Fed has a checkered history, but through it all the 10-Year [Treasury] figures out how to price itself,” said Alexander Goldfarb, senior research analyst at investment bank Piper Sandler, who noted the 10-Year Treasury has hung in the 4 percent range for much of the last year, as well as this week.

“It goes up, it goes down a little, but credit spreads have been incredibly tight, debt is increasingly available across CRE capital markets,” he added. “So, yes, there’s drama at the Fed, and it provides great fodder for newspapers, but, ultimately, the market is speaking as far as access to capital.”

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is actually up 0.63 percent since the Sunday night announcement of Trump’s investigation into Powell; the S&P 500 is up 0.67 percent — although this might be more due to the swift reaction from congressional Republicans in tamping down the feud before it got out of hand.

Market strength aside, others in CRE argued against the move to hold a criminal indictment over Powell’s head. Carpenter defined it as “really wrong,” “baloney,” and “too strong a hand to play,” while Jon McAvoy, chief investment officer at PRP Real Assets, emphasized that Federal Reserve independence is “imperative to our nation.”

“I really believe we have a mismatch in this country between short-term political appointees and elections with the need for the nation to have long-term financial stability,” he added. “And that’s what the Fed is supposed to help us with.”

Historical precedent

The complexities inherent in anything affecting leadership at the Federal Reserve are due to its intricate relationship between U.S. fiscal policy and monetary policy.

The big fear, particularly among market watchers, is that by threatening Powell with criminal charges, Trump is setting a new precedent for how a president can act toward a Fed chair — in turn creating a situation where a nominally independent central bank can be browbeaten into action by the sitting president, particularly one presiding over nearly $40 trillion in public debt.

“If there’s political pressure on the central bank without a change in the mandate, that’s problematic because it’s coming from the government having a fiscal need from the central bank,” said Juan Flores Zendejas, a professor of economics and history at the University of Geneva.

“And that’s always bad news because this political pressure means you can damage the actual credibility, and even the capacity, of the central bank to succeed in doing what it’s supposed to do,” he added.

Roughly $9 trillion in U.S. government debt — T-bills, T-notes, T-bonds, ranging from short-term to long-term — is scheduled to mature in 2026. But, as short-term interest rates remain higher than they were for much of the past 15 years, it becomes more expensive to refinance long-term maturing debt that was issued under the historically low interest rate regime that reigned from 2010 to 2022.

For example, refinancing a portion of the national debt this year at a 2.6 percent interest rate, rather than a 3.6 percent, could potentially save the federal government hundreds of billions of dollars a year in interest payments going forward.

“What [Treasury Secretary] Scott Bessent and Trump are trying to do is roll a majority of Treasury bills into short-term maturities, because they know they can control short-term, but not the long-term, interest rates,” explained Carpenter. “And the only way they can control the short-term rate is if the Fed lowers it — it’s a pure political move to apply pressure on Jerome Powell to lower rates.”

The fear, of course, is that by cutting interest rates too quickly, the money supply could increase to a dangerous level, running the economy too hot and pushing consumer prices higher.

“In a sense, you can artificially push rates down below the rate that the economy functions best at, and, from that standpoint, you could create inflationary pressures down the road,” said Bailey.

To some economists, this play is straight out of the ancient history books, and one being initiated by Trump and Bessent by design to lower the threat of the $38 trillion national debt.

“Every student of monetary policy history knows that governments want to monetize debt, and the politically easy thing to do is to inflate your way out of a debt problem,” said Christopher Thornberg, founding partner at Beacon Economics. “This has been done going back to Rome and the great inflation of the 3rd century CE. There’s nothing here that we haven’t seen before.”

And then there’s the separate argument of the precedent concerning Fed independence altogether. Political pressure has been deployed in the past, and has largely been effective (although certainly not threats of imprisonment).

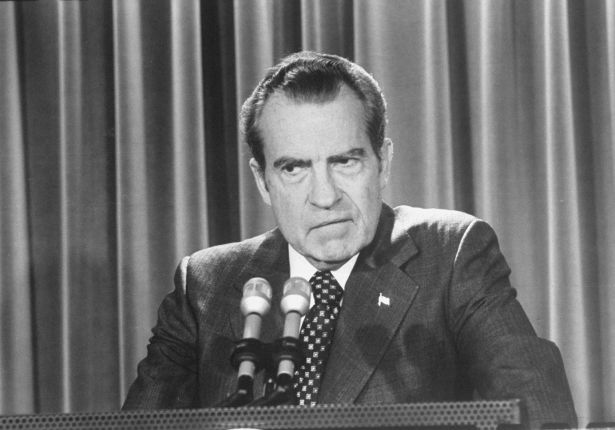

Richard Nixon infamously pressured his friend and former White House economic adviser, Arthur Burns, after appointing him Fed chairman, even joking at Burns’s January 1970 swearing-in ceremony, “I respect his independence, however I hope that — independently — he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed.” Burns’s diaries, as well as the infamous recorded tapes of White House meetings, revealed that Nixon repeatedly implored Burns to “keep the money supply up!” and prioritize the president’s re-election goals over the broader economy.

Lyndon B. Johnson also coerced Fed Chair William McChesney Martin in the 1960s, going so far as to shove him into a wall at his Texas Ranch. Long before there was a Federal Reserve, in the 1830s President Andrew Jackson waged (and won) an honest-to-god legal and political battle against Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States, the 19th-century forerunner to the Fed, over allegations of favoritism toward wealth merchants and speculators.

“We can start with there was precedence for this — Nixon, Johnson, Reagan, they all challenged and pressured their Fed chairs,” said Polsinelli. “This is not a new thing.”

Others questioned the perceived need for the Fed to be an independent body to begin with.

“I don’t think the Fed should be independent. I think the Fed should be hand-in-hand with the president,” said Greg Kraut, co-founder and CEO of KPG Funds. “I’ve never agreed the Fed should be an independent body. The whole idea of the Fed being independent is complete nonsense.”

Polsinelli added that even if Powell and the Fed are seen as independent, it shouldn’t protect them from the consequences of poor policies.

“It doesn’t mean that independence should shield Powell from review over mistakes or choices he’s made that have done harm to the economy,” she said. “Without questioning him, you have the opposite effect.”

But Zendejas countered that any idea that the Fed is not democratically accountable to its dual mandate of price stability and full employment — one legally passed by Congress in 1977 — is both misconstrued and misguided.

“This argument can be contested to the extent that this dual mandate is given by a government which is democratically elected, so in that regard it doesn’t mean the mandate can’t change,” he said. “But governments have given these mandates.”

And no less an eminence than Jamie Dimon, chairman of J.P. Morgan Chase, said earlier this week that, “Everyone believes in Fed independence. … Anything that chips away at that is probably not a great idea, and in my view will have reverse consequences.”

Uncertain times

These reverse consequences that Dimon hints at have been carefully noted by financial analysts and seen in the failure of other countries.

Francesco Pesole, a foreign exchange strategist at ING, the Dutch multinational banking firm, wrote a memo following news of the Powell investigation, calling the development “explosive,” and adding that any perceptions of the loss of Federal Reserve independence would fuel a “major depreciation” of the U.S. dollar.

“The downside risks for the dollar from any indications of further determination to interfere with the Fed’s independence are substantial,” Pesole wrote. “A sharp steepening of the [bond] curve could take the dollar on a fall.”

Aside from its impact on the dollar, higher long-term bond yields are one of the main symptoms of inflation, the horrible phenomenon of increased prices on just about everything, and these yields are unfortunately tied not just to investor sentiment toward the safety of U.S. Treasurys, but also to the fiscal responsibility of U.S. politicians to manage the nation’s annual budget deficits.

Since 2020, the U.S. government, under both Trump and Biden, has averaged an increase in the budget deficit of $2.5 trillion per year. Just 17 years ago, in 2009, the entire federal debt was only $12.3 trillion.

“We’re right on the edge of diving into a fiscal crisis,” said Thornberg. “It can get very ugly very quickly, and it will have massive ramifications for the global economy and for financial markets.”

Even the idea of lower short-term interest rates has been criticized by some market players, especially after the emergency cuts initiated by Powell in 2020 and 2021 set the stage for price increases across the economy.

Reven Capital’s Carpenter noted that “the lower the interest rate, the higher the inflation, and the perfect example of that was in 2021.” That year, interest rates were below 1 percent, and asset values shot through the roof as investors poured into hard assets like CRE to find yield that wasn’t there in fixed-income bonds, all while the economy ran hot against a dimly perceived supply-chain bottleneck.

“Dropping rates inflates asset values and allows people to refinance at higher valuations (i.e. cap rates), so they’re borrowing more than normal, and it puts companies at financial leverage risk,” he said. “But, long term, you don’t want the rates super low -— you want fixed-income to make money on government debt, and you want realistic cap rates on commercial real estate.”

Others in the market aren’t quite as concerned about the long-term threat of another bout of inflation stemming from artificially lower rates.

“I think inflation is complete hogwash, and I think the idea of 2 percent inflation is B.S. — the standard rate should be 3 percent,” said Kraut, who said COVID and supply chains caused price spikes. “I don’t see any indication that if you lower interest rates it will lead to inflation. Lower interest rates will spur economic growth.”

Kraut added that if the Federal Reserve doesn’t cut interest rates by at least 150 basis points this year, then he believes the U.S. will fall into “a major recession, almost a depression.”

Even so, PRP’s McAvoy emphasized that “political manipulation of the Fed is a real concern,” and that while a risk premium for volatility is already priced into the bond market, “the question is whether this next moment [with Powell] will cause a need for that premium to have a future increase.”

The more important point is the reason Fed watchers like McAvoy, Thornberg, Carpenter and even Dimon are so concerned about political manipulation of the Fed, and its impact on the strength of the dollar and bond market, is due to what has happened in other countries.

In July, Rebecca Patterson, an economist who has held senior positions at J.P. Morgan Chase and Bridgewater Associates, wrote a New York Times op-ed once the first real rumblings of Trump encroaching on Powell’s independence could be heard.

Patterson listed how Victor Orban in Hungary stacked the deck against his country’s central bank by adding handpicked council members to the monetary policy committee and passing laws in 2011 to strengthen his direct control over the bank. Since then, credit ratings agencies have downgraded the country’s debt to junk status, in turn raising borrowing costs across Hungary and causing its currency to weaken against the Euro.

She also documented how Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan issued a decree in 2018 to assume total control across the country’s central bank, and has since hired and fired numerous monetary policymakers. The results speak for themselves: The Turkish lira has lost 88 percent of its value against the dollar since 2018, and inflation in Turkey rose from 15 percent to 88 percent within seven years, while the country’s 10-year government bond yields reached as high as 30 percent.

Zendejas said the most pertinent parallel to Trump’s actions with Powell come out of Argentina, where then-President Cristina Fernandez fired Martín Redrado, president of the Central Bank, in January 2010 after he rejected her public demands that he resign for refusing to use the country’s foreign currency reserves to pay down the national debt.

Zendejas said the messy fight between this chief executive and her central banker immediately led to a depreciation of the peso and an increase in inflation, which was already relatively high in Argentina.

“It was a mess, and had a long-term effect on both the credibility of the central bank and its capacity to manage inflation and interest rates, and the capacity for Argentina to avert capital flight and stabilize its economy,” he said.

Next steps

Even without opening a criminal investigation, Trump won’t have to wait long to have a new leader at the Fed: Powell’s term expires in May, and the president will get to select a successor one way or another.

For now, Senate Republicans like Thom Tillis and Lisa Murkowski have expressed their willingness to block Trump’s next Federal Reserve nominee until his actions against Powell are resolved, but at some point this year the Senate will need to take up a nominee brought forward by a president who demands lower interest rates and isn’t afraid to trample over institutional norms.

“Are there bulwarks? If you asked the question 15 months ago, a lot of people would’ve been quick to answer a certain way,” said McAvoy. “Right now, enough folks are questioning the norms, and the strength of the norms, that no one would want to answer that affirmatively at this moment.”

The list of potential successors to Powell is relatively short, and include former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh, current Fed Governor Christopher Waller, BlackRock executive Rick Rieder and current Fed Governor Stephen Miran. But the name that stands out among them is current White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett, a man widely believed to be a Trump loyalist who has been close to the president since his first term in office.

Just hours after Powell released his video to push back at Trump, Hassett made a television appearance in which he stated he “would expect that the markets would be happy to see that there’s more transparency at the Fed.”

“This guy? Come on, this is Mr. Dow 36,000,” scoffed Thornberg, referring to the title of Hassett’s 1999 book that predicted a Dow Jones Industrial Average of 36,000 by 2002 or 2004 — which didn’t happen for more than 20 years after publication. “I think most economists view this guy with something between contempt and disrespect. You put him in, and see what the markets think of him. But I’ve been amazed at how benign the markets have been to all this chaos.”

McAvoy also pegged Hassett as the favorite, pointing to his longtime allegiance to Trump.

“Some would argue there’s a benefit to him because he seems to have been able to get Trump’s ear in understanding larger economic issues,” said McAvoy. “I don’t know whether or not he will be independent, but I’m sure during the confirmation process that will be the central issue.”

Regardless of who succeeds Powell, and what comes next for the U.S. economy, there’s no doubt that by opening a criminal investigation into the existing Federal Reserve chairman, Trump has forever changed the relationship that body has had with the White House.

“Trump’s challenging the narrative and calling out the inconsistencies, and that’s something people should want,” said Polsinelli. “The Fed chairman is not supposed to be in an ivory tower making decisions that affect you and me and our families without challenge.”

But as Thornberg noted, Trump made his fortune in the 1980s by playing fast and loose with easy money policies and the junk bond market — and he eventually catapulted into personal bankruptcy that left his many creditors holding the bag for his own fiscal mismanagement.

“Trump is the original ‘pump and dump’ guy, and has been since the dawn of time,” said Thornberg. “He has no interest in the long run, or even a decade from now. All he wants is wins right now, and he’s willing to sacrifice the future to get those instantaneous wins.

“I think this is a terrible precedent,” he added.

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com.