The L.A. Fires and Housing: Here’s What It Could Take to Rebuild

Scale of the damage makes it an unprecedented task, but there are examples and tools for the private and public sectors

By Nick Trombola January 15, 2025 1:33 pm

reprints

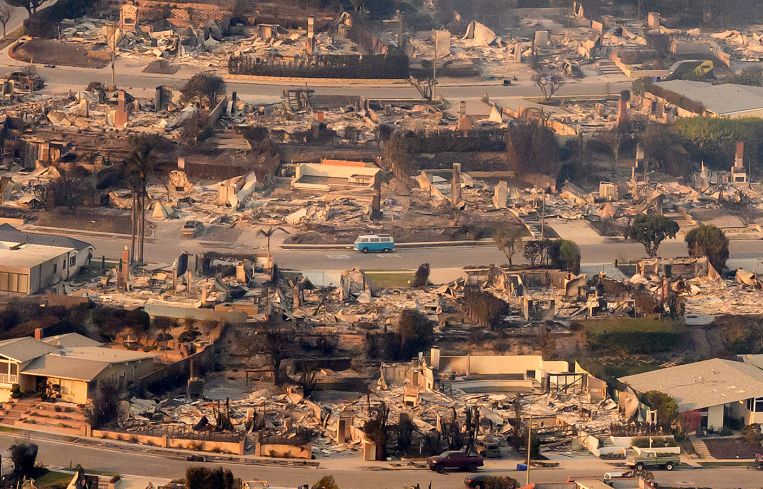

As Greater Los Angeles reels from the worst firestorms in the state’s history and firefighting crews make progress on containment, attention has begun to shift to recovery for the thousands of households across the region struggling with what to do next.

Building a single home or apartment in Southern California has been notoriously challenging, let alone building thousands at once, and many questions remain on what rebuilding efforts will even look like, not to mention how those efforts will affect the region’s housing market in the meantime.

As of Wednesday morning, the Palisades and Eaton Fires had killed at least 25 people and damaged or destroyed some 12,300 structures, numbers that are likely to rise in the coming days as authorities work to gain control over the disasters. About 5,300 of those structures were in Pacific Palisades, a relatively affluent neighborhood on Los Angeles’ Westside, adjacent to Santa Monica. The total cost estimate of the disasters, including rebuilding and economic loss, is more than $250 billion and rising, according to AccuWeather, exceeding the total cost of the entire 2020 wildfire season.

The full tally of affected households could be even higher, according to Michael Manville, professor of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, due to lingering smoke damage, long wait times for utility recoveries, and general reluctance to move back into a home where the surrounding community has been decimated. The result means thousands of people have been thrown into a Southern California housing market that was already in crisis before the fires.

“The upshot is that a lot of people who had been housed — who do have, for the most part, strong incomes — have just been thrust into the housing market, and they’re going to push up prices and rents, and also compete for contractors in an already tight labor market to get things rebuilt,” Manville said. “It’s a terrible situation, obviously, for these folks that have lost homes, and nobody should begrudge them their efforts to get themselves housed, but there will likely be trickle-down and ricochet effects throughout the housing market for many other people as well.”

That’s not even mentioning insurance fallout. Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs analysts estimated this week that the fires could cost insurers as much as $30 billion. That huge payout is likely to balloon premiums for residents who rebuild, as well as for other insured people living in fire hazard zones across Southern California. From 2018 to 2023, for example, in the wakes of 2018’s Camp and Woolsey Fires and 2021’s Dixie Fire, the average cost of home insurance in California catapulted more than 43 percent, according to S&P Global.

That’s if insurance firms even continue covering parts of Southern California at all. A recent report by CBS found that State Farm dropped some 1,600 policies in Pacific Palisades alone within the last six months, along with another 2,000 across the L.A. neighborhoods of Calabasas, Brentwood, Hidden Hills and Monte Nido.

In the aftermath of the 2025 fires, however, the first step for the thousands of displaced people is finding immediate housing. That’s both a difficult proposition in a region already suffering from an availability crisis and an effort that has caused an immediate spike in housing demand across L.A. County. Although California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s state of emergency declaration automatically bans rent increases of more than 10 percent throughout its duration, reports abound of some landlords already illegally raising prices to exploit the situation. Meanwhile, it’s unclear how the rental market will react once the emergency declaration is lifted.

A similar event in the state’s recent history presents a road map of just how much rents can rise amid high demand in the wake of disasters. In the months after the 2017 Tubbs Fire, which destroyed over 5,600 structures in Northern California, average asking rents jumped by nearly 36 percent in Sonoma County and 23 percent in Napa County, according to Zillow data commissioned by The Guardian at the time.

Greater L.A. contains many more options for housing than either of those two counties, but the region still suffers from a severe dearth of available units. L.A. County alone has a shortage of about 500,000 affordable units, according to the county’s homelessness initiative. Housing permitting and construction in Southern California is also a historically long and expensive process. The current tally of damaged structures in the Palisades and Eaton fires accounts for more than half of all building permits issued in the county throughout 2023, according to U.S. Census data.

Many of the people who lost their homes are likely to rebuild, said Henry Manoucheri, chairman and CEO of L.A.-based investment and development firm Universe Holdings, but the process can take years. Those displaced will need shelter in the meantime, raising the level of competition for L.A. County’s 9.6 million residents, more than half of whom are renters.

“It’s not going to be a six-month window. This is going to be several years,” Manoucheri said of the increased demand for housing due to the fires.

“I think, ultimately, a lot of these people will end up rebuilding these homes, but you’re going to have 3,000 or 4,000 people applying for permits, and we are in a city which has the most difficult, longest development challenge than anyplace else,” he added. “You’re talking about three years, five years by the time you’re done litigating with the insurance company, and you’re going back and forth to City Hall negotiating … so you’re going to have a tremendous amount of time wasted before [Pacific Palisades] gets built back up.”

Regarding Los Angeles specifically, the damage caused by the Palisades Fire could also pack a wallop to the city’s tax revenue collection in the coming months.

While the city is still calculating the potential losses, it’s likely that business tax revenue in the Palisades will be close to zero, according to Matthew Crawford, assistant director of L.A.’s Finance Department. Property tax revenue will also likely take a big hit, he said, in what could amount to a combined millions, if not tens of millions, of dollars of lost revenue come tax season. A huge drop in tax revenue could compel cities to approve rebuilding permits faster than normal, but for now the scale of the revenue impacts are difficult to quantify.

“The real story will come out in the numbers,” Crawford said. “We’ll know a lot more [once business taxes are due] by the end of February about what happened, and we’ll know much more when property taxes come in April. But until then we’ll really just be guessing.”

Gov. Newsom and L.A. Mayor Karen Bass also signed executive orders in recent days aimed at cutting red tape around the rebuilding process for homes destroyed in the fires. Those include waivers for environmental reviews like the California Coastal Act and California Environmental Quality Act, and expediting permitting reviews, as well as fast-tracking approvals for 1,400 housing units across L.A. Newsom’s order also includes extending price-gouging protections for building materials, construction and storage services, among other essential services, until next January.

Opinions about whether those orders will make a significant difference depend on whom you ask.

While the expediting efforts can’t hurt, Manville said, much of the delay that occurs around housing construction in Southern California can be traced to multifamily developments, rather than single-family homes, which is the vast majority of housing destroyed in the 2025 fires.

“A lot of the things that might be chalked up to delays just don’t necessarily come from single-family homes,” Manville said. “Multifamily homes are the ones most likely to have various requirements attached to them, under pressure to use union construction labor and so on — that just doesn’t really happen as much with single-family.”

Delays in single-family construction typically involve the availability of contractors, materials and construction labor. “A lot of the bottlenecks here are not necessarily things the government can alleviate,” Manville said.

Loretta Thompson, a partner at international law firm Withers, said she’s seen fast-tracking efforts for single-family communities work before, though, albeit at a smaller scale.

A 2002 gas explosion in Torrance, in L.A. County’s South Bay, nearly leveled an entire city block, damaging some 150 homes and injuring 10 people, according to media reports at the time. In the aftermath, the city essentially assigned a special inspector to help expedite the rebuilding of the community, Thompson said, resulting in a neighborhood completely rebuilt less than two years later.

“I think that’s the kind of thing that these cities are going to adopt,” Thompson said. “Malibu already has special consultants that come on as needed to help with expediting rebuilding. … Pasadena has also done that before when fires have affected them. Altadena, same thing. This is not the first rodeo for any of these communities with fires. So it’s a matter of the commitment of the cities to assign special expediters to get the places scraped, first of all, from toxic debris, then get plans approved, and I think it’s entirely feasible.”

As far as short-term, anti-price-gouging laws go, Manville said their effectiveness depends upon the commodities that the law is aimed at. The risk of such a law in this case is that it could slow the flow of materials into an area that desperately needs them.

“If you want supply to increase and flow to this place, suppressing the price paid in that place is not going to help you do that,” Manville said. “There are arguments out there that say this is a basic fairness thing to do, but I think the textbook analysis regardless of how you feel about the fairness aspect is that if there’s a shortage of these goods, aggressive enforcement of price gouging is not going to help that shortage, it may exacerbate it.”

Still, for Thompson, a lifelong Southern Californian, it’s not a question of if communities will rebuild, but how.

Although the Palisades and Eaton fires are clearly the worst in the state’s history, the region is no stranger to fires, Thompson said have been coming her whole life. In the wake of these fires, California instead has the ability to lean on major trading partners for help with supply issues, source new and better building materials, and change the way communities develop in disaster zones in order to become a model for how a region can reconstruct itself in an age of worsening climate upheaval, she said.

“California is in a really great position, as a strong state and the fourth-largest GDP in the world, to make an example of rebuilding in a sustainable manner that is really applicable to future fire events,” she said. “Because the fires are not going to stop.”

Nick Trombola can be reached at ntrombola@commercialobserver.com.

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)