Commercial Real Estate in 2024 Was All About a Tough Turnaround

Higher borrowing costs, political uncertainty, bank failures, and booms and busts in asset classes — this year had a lot to get through

By Brian Pascus December 11, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

On April 8, 2024, millions of Americans briefly left their homes, schools and workplaces to view the Great North American Eclipse, the first total solar eclipse visible from this part of the globe in nearly seven years.

Like any solar eclipse, the moon shifted directly between the sun and the Earth, thereby briefly (and totally) obscuring any view of our one star from Texas to Maine.

In some ways, this cosmic event became both a harbinger and a fitting metaphor for national commercial real estate in 2024. The industry finally seemed ready to eclipse the nightmarish era of high interest rates that began in 2022, and much of the bad juju about office space seemed to dissipate as employers began issuing return-to-work mandates and signing up for big leases.

At the same time, the real estate world remained stuck between the promise of increased transactions and true value discovery on one hand, and the peril of renewed inflation amid the uncertainties of a second Trump administration on the other.

“For most people, it’s been a very unpredictable year,” said Laura Rapaport, founder and CEO of North Bridge, a firm specializing in environmentally driven C-PACE financing. “The rise in interest rates, the lack of activity, banks pulling back, changing valuations, and uncertainty surrounding the election has created a perfect storm of a stalemate and a race to scramble to find [capital] solutions.”

For much of 2024, capital stacks remained out of balance due to persistently high interest rates, which left capital markets impaired and both borrowers and lenders in need of time, money, and maybe a little bit of luck to sort out unfavorable macroeconomic factors.

The 10-year Treasury note, the industry benchmark for long-term financing, opened the year at 3.9 percent, rose as high as 4.7 percent in late April, fell to as low as 3.6 percent in mid-September, and proceeded to tick back to 4.4 percent following the election in November. This relative flatlining of the long-term rate over 11 months created similar conditions in the transaction marketplace.

The number of CRE investment sales declined 4.7 percent year-over-year nationwide in the first three quarters of 2024 and was 33 percent lower than the average from 2017 to 2019. Those metrics barely improved from the investment sales data from the first quarter of 2024, when sales were also down 33 percent relative to the 2017-to-2019 average, according to Newmark capital markets data.

“It was a fine year, it wasn’t an awful year, but in a year marked by lots of volatility and a lot of things going on in the world, there was surprising amount of consistency in the real estate world,” said Michael Gigliotti, senior managing director and New York Office co-head at JLL. “It never got really bad and it never got really good.”

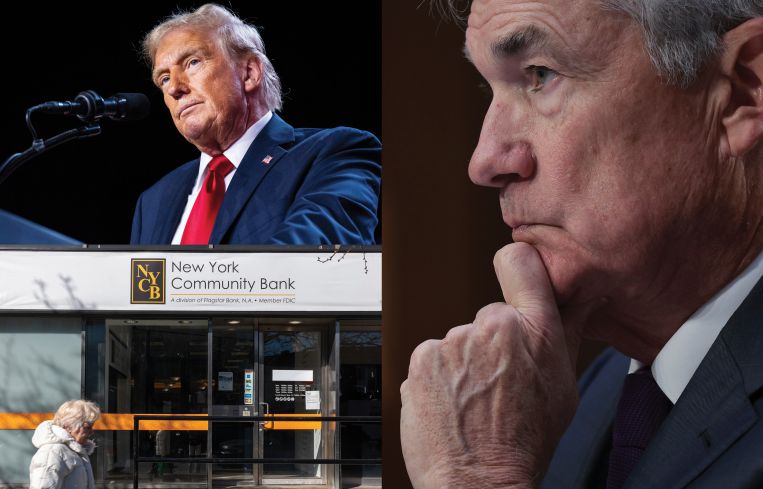

As for the short-term interest rate, or federal funds rate, CRE players watched in horror as Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell dithered for much of the year on his intention to finally make cuts — as he indicated in his December 2023 remarks. Instead, the central bank left the overnight lending rate between 5.25 and 5.5 percent (its highest level in 17 years) for nine months, before mercifully initiating cuts of 75 basis points in September and November.

“This was definitely the year we went through five stages of grief, from denial to acceptance,” said Scott Rechler, chairman and CEO of RXR. “During the year, owners and banks began to capitulate to where values are and acknowledge that, even if rates come down in the short term, longer-term, rates aren’t returning to where they were in this abnormal last decade of extremely low or zero percent rates.

“There’s been more of a facing of that reality,” he added.

Upside-down banking

Reality hit the CRE industry square in the solar plexus early on in 2024. The stock of New York Community Bank (NYCB) — a Queens-based lender with 420 branches and assets exceeding $100 billion — declined 83 percent in February to less than $2 per-share on the heels of an announcement that the bank reported a $252 million loss tied to loans on its office and rent-regulated multifamily properties. Fourth-quarter credit losses in 2023 had reached a staggering $552 million.

After replacing its CEO twice in one week, the bleeding stopped after NYCB received a $1 billion capital infusion from investors tied to former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.

Even so, the near collapse of a top regional bank elicited fears of a 2023 regional banking crisis redux, when Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank all fell within six weeks and cast a critical eye on the health of the CRE assets within the entire banking system.

“In 2024, we saw a lot of banks be hesitant to negotiate with borrowers, they held firm, and what we’re seeing now is a lot of losses of larger banks. They’ll be taking massive losses,” said Chad Carpenter, founder and CEO of Reven Capital, a CRE investment firm, referring to Wells Fargo’s October 2024 announcement that it will lose up to $3 billion on its office loan portfolio. “Once those big losses are published, people will say, ‘If they have those big losses on those office buildings, then how many more losses do they have on their commercial real estate?’ ”

Carpenter emphasized that impaired CRE assets like office loans are a major proportion of regional bank balance sheets, and he believes 70 percent of all leveraged, non-trophy buildings will get restructured and foreclosed on. That will put many regional banks at further risk.

“Who has the bulk of the loan exposure? It’s the regional banks. The banking system owns 51 percent of all commercial real estate debt,” said Carpenter, who added the other 49 percent is owned by commercial mortgage-backed securities investors, life insurance companies, debt funds and mortgage real estate investment trusts. “Of the 51 percent, regional banks own 70 percent of it, and the regional banks have been slower to acknowledge impairments. So people need to take a hard look at some of these regional banks who have office loan exposure.”

Rechler noted that in 2024 regionals such as Dime Community Bank and Valley National Bank saw their stock prices rise after raising equity. But their stocks still trade at a deep discount compared to their historical highs, opening the doors for private credit to continue its steady march forward as both a rescue option and an alternative when it comes to balance sheet banking.

“The reality is, as these tremors play through, you’ll have a more permanent place for the non-bank lender,” explained Rechler, who raised $1 billion in 2024 for credit and equity investment purposes. “We’re having conversations with banks on a daily basis about being a financing partner so they can serve their clients, or buying loans from them, where they are the originator and we’re the balance sheet that holds their loans.

“There’s opportunity in these situations where new structures and financial products will be created that will live on in this period and become part of the norm as we move forward,” he added.

In 2024, alternative lenders firmly entrenched themselves as a permanent fixture in the CRE financial system — with banks heeding the stiff regulatory agenda of the international Basel III framework — as CRE sponsors were more than willing to stomach their onerous terms amid a veritable liquidity desert.

In the first three quarters of the year, bank originations fell 24 percent year-over-year compared to 2023, a decline that was offset by increased lending from securitization, debt funds and insurance companies, according to data from Newmark.

Warren de Haan, founder and CEO Of Acore Capital, a CRE alternative lender with a $21 billion portfolio, said that in 2024 his firm focused on two origination vehicles: senior loans, with Acore routinely filling 65 percent to 75 percent loan-to-value on credit structure; and opportunistic credit, in which the firm specialized in providing senior debt and bridge capital solutions to get borrowers to the other side of underwater financings.

“Our universe of 500 borrowers mostly have capital structure problems, not fundamental problems, and we’re providing capital solutions to them from dollar zero to dollar 85 as a trusted, go-to lender,” said de Haan. “We’ve seen strong activity in our high-yield, opportunistic credit business, and our core business has rebounded significantly in the last three months [of the year].”

De Haan added that the optimism surrounding potential interest rate cuts by the Fed lasted about eight weeks at the start of the year before a realization set in that sellers wouldn’t sell and transactions would be hung up. He said the market “went into the doldrums” until August rolled around, at which time the spectre of falling interest rates revived the animal spirits for private credit.

“Come around to the end of summer, we have seen an increase in our pipeline that is consistent with our peak production years,” said de Haan, who tracked $2 billion in deals closing in November alone. “That’s harking back to our peak days, as opposed to what we’ve been seeing through 2023 and the first half of 2024, and it feels good. It feels like business is back.”

Other non-bank lenders, including Josh Zegen’s Madison Realty Capital, found themselves busy as construction lenders, bridge lenders, note purchasers, and as lender servicers or financers, providing banks, private credit funds and mortgage REITs with needed capital.

Zegen told Commercial Observer that his firm, which carries $21 billion in assets, financed a $400 million deal to build a 50-unit condo on Fisher Island in Miami Beach; a $133 million mortgage to finish construction of a 51-story, 379-key Marriott hotel in New York City; and secured $2.04 billion in equity commitments for its sixth U.S. real estate debt fund.

“You’re starting to see the market finally start to break a bit on deals that might have been nonperforming [in the past],” said Zegen. “With this theme of higher-for-longer [interest rates], people feel they have to do something.”

The rate cut that wasn’t — until it was

It’s impossible to examine commercial real estate without understanding the impact of interest rates. For much of 2024, interest rates — and the lack of the long-promised cut to the federal funds rate — dominated the discussion in CRE.

Some players characterized Fed Chair Powell’s delay throughout the year as a deliberate attempt to mask the false impressions needed to fight inflation with one hand while simultaneously reassuring a nervous capital markets system with the other.

“While rates didn’t necessarily come down, the Fed used their rhetoric to keep financial markets loose, the stock market open, the bond market going, and spreads tight, so that it effectively induced the equivalent of reducing rates without having to cut them,” said Rechler. “It gave banks a chance to build appropriate reserves, and capital formation a chance to position itself.”

Powell’s rhetoric fooled everyone. De Haan recalled meetings and conferences with leading executives at the start of the year opening with speculation about not if rates would be cut in 2024, but how often.

“There was a moment in time, early in the year, where there was a lot of optimism, where we all believed rates would be cut,” de Haan recalled. “I remembered listening to very powerful people in prime banking seats talk about whether it would be three cuts or five cuts.”

Instead, investors waited a full nine months for the federal funds rate to fall for the first time in two and a half years. The waiting game created a dichotomy for CRE: a slow first half turned on its head once rates dropped in September.

“It seems like it’s been a tale of two halves, where the first half of the year was largely a similar environment to 2023, but then the third quarter and fourth quarter has probably seen elements of 2021, where activity levels have been extremely high,” said James Millon, president of U.S. debt and structured finance at CBRE.

JLL’s Gigliotti echoed these sentiments, calling the back half of the year among the most active markets in recent memory.

“That month or so leading up to when we knew we’d get that rate cut — so August into that rate cut in September, and then a few weeks after that — was as active as any market that I can remember,” he said.

Nowhere did the improved activity levels find their way to fruition more than in the beleaguered office sector, which saw its year-to-date sales metrics rise 17 percent compared to 2023, and investor allocation rise from 12 percent in 2023 to 15 percent in 2024, per Newmark.

Back at the office

“I think 2024 was the year for office in a couple of ways,” said Rechler. “People came back to the office, so that was a clear deciding factor, and the companies that came back realized they didn’t have enough space. So you saw a level of leasing activity, which going into the year we forecasted it would be 2018 levels, and it may even be higher than that.”

Manhattan office leasing exceeded 30 million square feet in November, hitting that threshold for the first time since 2019, according to Colliers. Manhattan, the epicenter for American office, saw its office leasing activity grow by 5.6 percent during the third quarter of 2024 to 8.6 million square feet, its strongest quarterly volume in two years, per Colliers.

“I’ve always said office will be like malls. Once you get through the period where it’s toxic to investors, there will be a delineation between Class A office that attracts tenants and does well — and will be priced that way — versus the other buildings,” explained Rechler, who added that RXR will have bought positions in more than 7 million square-feet of office in 2024.

Carpenter, an office investment specialist, called 2024 a bifurcation between “the haves and the have-nots,” where the best office buildings in the best locations have seen “tremendous demand” and everyone else is “in trouble fighting for tenants.”

“We’ll see buildings being demolished, we’ll see bankruptcies, we will see loan extensions, and probably the most interesting thing I’ve seen is the loan maturities,” he added.

Gigliotti said every product type that his team represents has more bidders than it had a year ago, including office, which today has double the bidders.

“In 2023, we had 43 groups bid on office, and, in the last three months [of this year] alone, we’ve had 83 groups, so there’s double the amount of lenders willing to bid on an office deal compared to a year ago,” he said.

Mary Anne Tighe, CEO of the New York tri-state region at CBRE, said two factors drove the renewed acceleration of capital back into the office sector. First, there was the internal growth and need of private equity firms, hedge funds and law firms to distinguish themselves by leasing high-quality space. That has caused a run-up in pricing and an accompanying absorption of Class A properties.

Moreover, Tighe added that four years after the pandemic, most businesses in the private sector realized the benefits of remote work aren’t all they were cracked up to be.

“In the pandemic, the glow of remote work, and the glow of the technology that supports it, arrived, we went overboard in embracing the concept, and really forgot the fundamentals of human nature,” she said. “Whenever you do something that’s alien to human nature, it’s not a lasting trend.”

No transaction better encapsulated this renewed belief in office than the massive $3.5 billion commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) refinancing that Tishman Speyer and Henry Crown & Company closed in October on Rockefeller Center in New York City, in a deal co-originated by Bank of America and Wells Fargo

“When you think about office recovery, when you get the debt markets to open up that were totally shut, in this case with [single-asset, single-borrower CMBS], it’s a good first step in terms of seeing liquidity re-enter the market,” said Rechler.

Others remain skeptical about the long-term health of the office market, especially from a capital markets perspective.

Madison Realty Capital’s Zegen noted that with so much value destruction and almost every sponsor refinancing into a higher interest rate landscape, the biggest challenge to the office market remains the inability of investors to get their money back. And, with the office market still anywhere from 15 percent to 30 percent of bank balance sheets as well as insurance company and institutional investor allocations, an important part of the capital markets system remains, for lack of a better term, clogged.

“It’s hard to reallocate capital into the office sector,” Zegen said. “It’s the albatross of commercial real estate, and, while it will pick it, it’s something that will bog down the system.”

With these points in mind, others have examined the improved leasing and occupancy data and have found fundamentals that confirm there is current and future demand for office space across the nation, particularly in the busiest central business districts.

“I’m still very bullish on office. I think it’s the most oversold asset class that I’ve seen in my entire career,” said CBRE’s Millon. “People who are taking risk in financing, or selectively buying the right type of office, will be compensated for that.”

The other guys

It wasn’t just office that returned (somewhat) to form in 2024. The prospects for multifamily, industrial and data centers all brightened during this year of transaction recovery.

At just under $100 billion, national multifamily investment sales rose 6 percent compared to the first three quarters of 2023, while, at $30 billion, multifamily institutional investor acquisition volume increased by 53 percent compared to last year, per Newmark data.

Yardi Matrix reported that roughly 329,000 apartment units have been absorbed nationally through 2024 and sector occupancy is 94.7 percent, “putting the market in line for one of its better recent years.”

“A lot of supply hit the market this year, we’re still expecting more next year, and financing has been challenging, for sure. But the bright spot looking at multifamily this year is that a lot of those high-supply markets are seeing pretty good absorption,” said Dan Dooley, chief investment officer at Coastal Ridge, a multifamily investor and operator.

Most importantly, the dreaded need to shore up billions of dollars of multifamily investments made in 2020 and 2021 with cheap, short-term, floating-rate financing turned out to be a chimera, as lenders and sponsors alike discovered that in 2024 much of that gap leverage was ready and waiting to rescue underwater capital stocks through preferred equity and mezzanine debt positions.

“In multifamily, we didn’t see the crisis that everyone predicted because the debt markets were super liquid,” said Patrick McBride, co-founder and managing partner at Coastal Ridge. “Multifamily is still a very preferred asset class, and, as banks trafficked out of other asset classes, that liquidity helped support what might have been a bit distressed.”

Metrics also turned out strong for the industrial sector, in part because underlying dynamics for demand stayed strong. This was especially true for newer space, even after many tenants overcommitted to space during COVID’s e-commerce boom.

National vacancies stood at 7 percent through the first nine months of the year (compared to 3.8 percent in December 2022), but national rents rose by 7.1 percent between September 2023 and September 2024. This was even as supply surged, with industrial completions totaling 283.1 million square feet through the end of September, higher than any year recorded before 2020, according to Yardi Matrix data.

Franz Colloredo-Mansfeld, chairman and CEO of Cabot Properties, an industrial owner, investor and operator, said the sector only saw 80 million square feet of leasing through the first three quarters of the year, which was down 60 percent from the same time last year. But demand for newer space exceeded 180 million square feet.

“Buildings that are over 20 years old lost occupancy by millions of square feet,” he said. “So the trends you’re seeing in office, with Class A buildings leasing and everything having a terrible time, there’s a little of that going in our business, too.”

Ultimately, no asset class established itself in 2024 quite like data centers, which received billions of dollars in fresh capital in anticipation that artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and the merging of the internet with the economy will continue unabated into the future.

Between now and 2028, global investment in new data center capacity will reach $2.2 trillion, or average $443 billion annually, according to Moody’s Ratings.

“I’ve never seen anything like the growth we’re going through right now in data centers,” said Millon, who added a new asset class is “virtually being created overnight” because of AI.

“The development wave associated with data centers, particularly around access to power, with long-term investment-grade, hyperscale tenants is unbelievable,” he added. “It’s nothing short of extraordinary.”

The Trump bump

Speaking of extraordinary, no honest account of the year in CRE could go by without referencing the remarkable political comeback of Donald J. Trump, who became the first president since Grover Cleveland in the 1890s to win two, nonconsecutive terms as president of the United States.

After a nearly two-year campaign riddled by indictments, arrests, felony convictions, assassination attempts, and threats of violence that recalled Jan. 6, 2021, the utterly peaceful and normal nature of Trump’s victory brought some calm to CRE circles.

“Of all the uncertainty that we had over the several months, the election was one of the biggest factors,” said Colloredo-Mansfeld. “So that’s now behind us, we know who won, and you’ve had a good rise in the market because of that.”

However, Trump’s endless penchant for political combat, devotion to high tariffs and massive tax cuts, and his general disdain for governing norms, has given the bond market pause. The 10-year Treasury has stayed above 4 percent since election night.

Lee Everett, executive vice president and head of research at Cortland, a multifamily firm, said that Trump’s policy agenda, which includes anywhere from $4 trillion to $7 trillion in deficit spending, has made CRE investors believe inflation may rear its ugly head in 2025.

“Deficit spending like that is inflationary by nature, and that doesn’t even get into the labor dynamics,” said Everett. “When you’re looking at a potential policy agenda of limited immigration, deportations, large tariffs and deficit-funded tax cuts, you’re looking at a likely higher inflation environment.”

Gigliotii said that, despite whatever Elon Musk might be promising in terms of government efficiency, investors are not betting this will be a cost-cutting administration, and that the market is treating a second Trump term as inflationary. He cited the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) forward curves, which represent market-implied future settings for one-month and three-month SOFR terms, which today are at 4.58 percent and 4.52 percent, respectively.

However, Gigliotti said the amount of liquidity out there — and “the sheer desire to transact, the capitulation of sellers, and the pent-up demand of buyers” — will beat out the cost of capital.

It’s a sentiment shared by many, as, at the end of the day, regardless of who serves as president, in CRE at least, capital remains king.

“There’s so much money on the sidelines,” said Colloredo-Mansfeld. “There’s a general sense in the commercial real estate world that we’ve come through the worst of it and that people are ready to make deals.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com