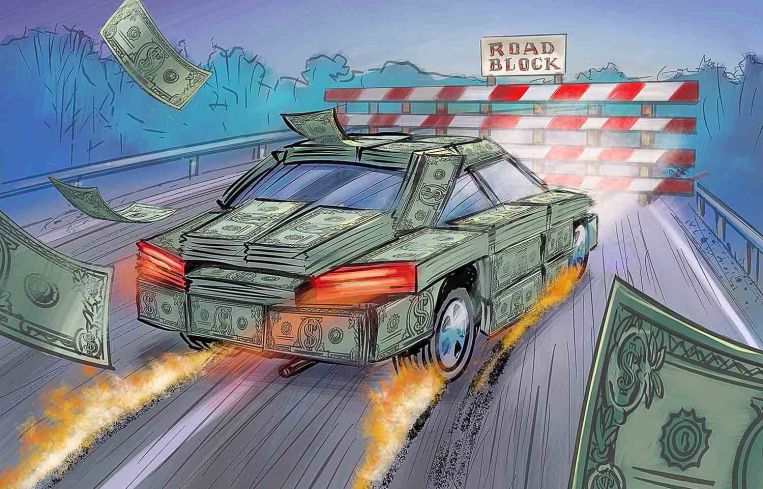

Commercial Real Estate CLOs Confront Rising Distress From Higher Interest Rates

Falling borrowing costs should prove a boon to bondholders.

By Andrew Coen October 2, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

As commercial real estate collateralized loan obligation (CRE CLO) issuance accelerated in 2024, so did mounting distress due to rising interest rates.

The 2024 U.S. CRE CLO volume was $6.8 billion as of Sept. 20, already eclipsing 2023’s total of $6.7 billion, according to data from Green Street.

While issuance was up, 10 of the top 20 CRE CLO issuers saw rising levels of distress in 2024 through July 31, according to CRED iQ, a data and analytics platform. That distress was led by Fortress (31.3 percent of delinquent loans) and Granite Pointe (28 percent of delinquent loans). CRED iQ’s analysis also showed a high percentage of loan modifications from the top CLO issuers, including 75.2 percent from KKR, 60.4 percent from Arbor Realty Trust and 60.3 percent from Granite Pointe.

The trouble within CRE CLO loan pools comes despite the vehicles having built-in safeguards to protect bondholders compared to other securitized products with similar names that became infamous during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

CLOs differ greatly from collateralized debt obligations, which developed a negative reputation for driving a big part of the credit crunch contributing to the GFC due to a heavy concentration in risky subprime residential mortgages. But, while CRE CLOs proved more resilient amid the economic storm clouds of 2008, thanks to built-in mechanisms tracking cash flow, these short-term floating-rate loans issued for pools of transitional commercial properties have hit their own roadblocks today in a higher interest rate environment.

Mike Haas, founder and CEO of CRED iQ, noted that a major factor causing distress in CRE CLOs — one that has a similar theme to the GFC — is a heavy component of pro-forma underwriting, which is predicated on a borrower’s ability to execute business plans to achieve higher rents and profits.

“CRE CLOs were predominantly floating-rate loans, and 2021 was a record year of issuance at a time when rates were low, cap rates were low, and valuations were at a peak,” Haas said. “Every month we are seeing the uptick in distress for CRE CLOs as borrowers are unable to afford paying their high debt service amounts out of pocket since the rents aren’t high enough.”

While CLOs have encountered their share of headwinds in the last couple of years, the product has held up reasonably well overall from a distress standpoint, according to Darrell Wheeler, head of commercial mortgage-backed securities research at ratings agency Moody’s Ratings. Wheeler noted that the latest Moody’s Ratings data shows a 3.3 percent 60-day delinquency rate for CLOs, which is far lower than other distress rates experienced in the CMBS universe.

Wheeler said CLOs, which have higher leverage points than traditional CMBS loans — often in the 65 percent to 70 percent range — in many cases have additional borrowing from mezzanine lenders that prompts loans going into special servicing, but the senior debt has largely survived.

“With values of multifamily being down 20 percent and office values being down 24 percent, some of these borrowers may not have an economic interest in the properties anymore, so we have seen them go into special servicing,” Wheeler said. “Then the question is whether the mezzanine lender wants to become the equity, but we haven’t seen the first mortgages really show as much distress.”

Deryk Meherik, senior vice president of structured finance at Moody’s Ratings, said much of the challenges now facing CLOs and leading to modifications stem from the low-interest environment of the late 2010s and early 2020s just as the product was gaining popularity. He said the Federal Reserve’s decision to lower interest rates, starting with a 50 basis point cut at its Sept. 18 meeting, should provide a boost as borrowers begin the lease-up phase of their properties after going through a transition in 2022 and 2023.

The Fed lowered its benchmark interest rate by a half point to between 4.75 percent and 5 percent to end its streak of eight straight pauses on the heels of 11 hikes in 12 meetings between March 2022 and July 2023. The central bank raised interest rates to their highest levels in more than two decades after operating at near-zero borrowing levels for two years early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meherik noted that when interest rates were at near-zero levels and many prepayments on properties were occurring, CLO managers sought and received the ability to modify loans within certain parameters to keep them in the market. These modifications included adjusting the interest rates, terms or the balance if certain metrics were met. This strategy was met with a curveball when the Fed began aggressively hiking interest rates in early 2020, causing interest rate caps required by lenders for floating-rate debt to soar.

“There was a lot of loan modifications, but it seems that it’s helped to reduce stress in the pools as these loans have performed well. And, now, with this interest rate cut, which was very needed in every which way for everybody, I think it’s going to create a lot of relief,” Meherik said. “A lot of the loans that were transitional in 2022, 2023 are at the tail end of the business plan and they’re leasing off now, and I think this interest rate cut will be very helpful for them and for the product line in general.”

Moody’s Ratings and other credit rating agencies rate CRE CLO deals based on the borrower’s executions of a business plan. When those fail, deal structures enable managers to replace the troubled assets in the pool. Managers of revolving pools replaced troubled pools between 2018 and 2023 with an average of three months of impairment, according to Moody’s Ratings data.

While the higher interest rate environment has led to challenges for CLO managers seeking replacement loans that have cheaper cost of capital, Meherik said there has not been a large enough volume to cause a slowdown in the market. Moody’s rates all CLO assets in revolving pools since they aren’t publicly rated loans and are required to be given an assessment, according to Meherik.

Dylan Kane, managing director of Colliers’ capital markets group, stressed that the damage to CLOs from interest rate increases varied greatly depending on the property sector. Class B office assets were hit especially hard with lower rents coupled with an inability to refinance at higher borrowing costs.

“So all these pools are very different, and it really just depends on the construction of the underlying collateral in the pool,” Kane said. “Office is basically getting hit from both sides.”

Andrew Coen can be reached at acoen@commercialobserver.com.