New York City Could Do With More Hotel Rooms, But Myriad Factors Are in the Way

‘There are fewer hotels under construction right now in New York City, but that’s true all over the country.’

By Larry Getlen September 30, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

New York City has lost 6,000 total hotel rooms since 2019, with 3,000 of those lost in Manhattan, according to brokerage JLL.

Responsibility for the loss can be attributed to many factors, including to the 16,000 rooms — 9,000 in Manhattan — that were converted to migrant housing.

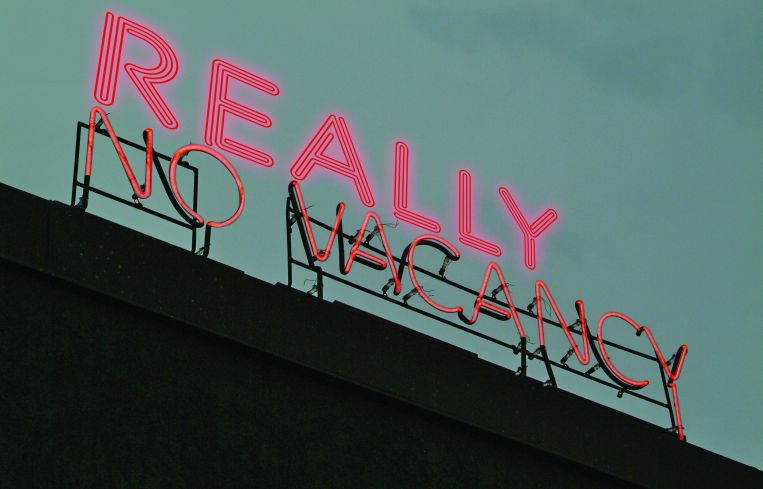

In addition, a special permit requirement for new hotel development, which some feel has turned New York City hotel development into a byzantine regulatory labyrinth, passed the City Council in 2021, making prospects for the future of New York’s hotel availability seem bleak. An evolving scarcity of hotel rooms in one of the world’s great tourist destinations, after all, could seem the equivalent of placing an “Open For Business, But Just For Some” sign on the city’s borders.

But talking with industry insiders shows a far more complicated reality, with signs of concern abutting an 87.2 percent hotel occupancy level in Manhattan, according to PwC — never mind 8,000 new hotel rooms in the pipeline.

Shimon Shkury, president and founder of investment sales firm Ariel Property Advisors, believes that reasons for concern are nevertheless growing quickly.

“The first is the lack of rooms in general, with drastically less than we had pre-pandemic,” said Shkury. The second reason, he said, is that about 12 to 15 percent of New York hotel rooms are being used to house migrants. A third reason is that tourism levels are close to where they were in 2019.

“In addition to that, you now have no ability to build hotels. The zoning requirements are such that you’re not allowed to build hotels — you need to get a special permit. What this all does is increase the average daily rate,” Shkury said.

The Citywide Hotel Special Permit does not actually remove the ability to build, but it does require the City Planning Commission to “consider a new hotel’s potential for adverse effects on use and development in the surrounding area before it can be established.”

Shkury is hardly alone in believing that these new requirements amount to over a year of regulatory hoop-jumping that discourages developers from attempting to build hotels in New York.

“I think, long term, it’s definitely going to be a problem,” said Mitchell Hochberg, president of Lightstone Group, a developer. “It’s somewhat mitigated by the shadow supply with the hotels that are housing migrants. But a lot of those properties are not going to go back to hotels after the migrants depart, because a lot of them were not viable as hotels, or were in outlying areas.”

According to brokerage JLL, many of the hotel rooms currently being used to house migrants will take over three years to return to use as hotel rooms, and approximately 50 percent of them will be placed permanently out of use.

“The government is not going to terminate all the contracts at one time, so contracts will roll off over time,” said Kevin Davis, CEO of JLL Hotels & Hospitality in the Americas. “Many of the owners will opt to use the hotels for longer-

term housing, or maybe alternative multi-family uses. So a lot of the hotels may not return to the system. A large number of the properties will also need significant renovation, so the time it will take to renovate and reposition the hotels could be somewhat elongated.”

Despite all the concerning bellwethers, some believe there is still reason for optimism over the fate of the city’s hotels.

Ian Dunford, director of research for the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council, noted that the perceived shortage in New York is actually part of a broader trend.

“There are fewer hotels under construction right now in New York City, but that’s true all over the country,” said Dunford. “That’s partially owing to the fact that construction costs are through the roof, just like fuel, copper, steel, lumber — it’s all higher, and it costs way more to build anything in New York City. I think we’re talking around $500 per square foot for a hotel. That’s close to office, and it hasn’t usually been like that.”

Dunford also said that, despite this, New York City leads the country in hotel rooms under construction.

“There’s going to be a rather large influx of rooms, because three casinos will likely get licensed, and each of those has plans to build incredibly large hotels,” said Dunford. “Additionally, there are multiple hotel projects registered with the city to obtain a special permit. If you look in the city zoning application portal, four projects have sought or gotten a special permit.”

The four applications are for hotels at 220 West 42nd Street, 5 Beekman Street, 10 Rockefeller Center and in Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens. Most seem relatively early in the permitting process. The Queens application includes a potential casino, and the Beekman Street application requests a landmark designation. (State officials in 2025 might award casino licenses for gaming proposals in New York City that in turn would include hotel rooms among their footprints.)

None of the applications even graze Upper Manhattan, one area where hotel room scarcity seems genuine. Lamont Blackstone, a real estate consultant who is acting executive director and past chair of Project REAP, a group promoting diversity in commercial real estate, noted that Upper Manhattan has long had a shortage of hotel rooms that has never been adequately addressed.

“East Harlem does not currently have a hotel. If you’re looking for a hotel in East Harlem, there isn’t one,” said Blackstone. “The closest one would be on the Upper East Side, the Courtyard around 92nd Street and First Avenue.”

Blackstone notes that the entire Harlem area is now, and has long been, hotel deprived. After the 1967 closure of the Hotel Theresa, which opened in the early 1910s and hosted boldface names over the years from Muhammad Ali to John F. Kennedy to Fidel Castro, Blackstone said that Harlem was without a hotel until Aloft opened one around the time of the 2009 Global Financial Crisis.

But the demand for rooms in the area, Blackstone said, has always eclipsed supply.

“[Hospitality consultancy] HVS did a market study in 2009 projecting that the Harlem/Upper Manhattan market could support something on the order of 1,100 rooms,” said Blackstone. “When the Aloft opened, it may have brought a few hundred keys. That suggested that there was still a significant untapped market for hotel rooms in Upper Manhattan.”

A few hotels have opened in the area since then, including the Renaissance New York Harlem Hotel, which is owned by Marriott. But Blackstone said that their cumulative total keys still don’t equal the demand the HVS study found 15 years ago.

“Arguably, the market has gotten better since then,” said Blackstone. “Knowing the growth of the area, there’s a very good chance that those demand numbers are out of date. The current numbers would be larger.”

And, whether such scarcity may or may not be taking root elsewhere in the city, rising hospitality costs have definitely become the norm, potentially reducing the attractiveness of New York City as a vacation destination.

In May of this year, The New York Times, citing CoStar data, noted that “the average daily rate for a hotel stay in New York City increased to $301.61 in 2023, up 8.5 percent from $277.92 in 2022.”

Davis believes the increased rates derive in part from the city’s emergence from COVID.

“In a typical recovery, you see an occupancy-led recovery, where hoteliers will typically run low rates in order to build occupancy. Then, as occupancy builds, they try to build rate over time,” said Davis. “Post-COVID, there were staff shortages. As a result, hoteliers couldn’t build occupancy significantly because they didn’t have the staffing to support high occupancy. So they charged higher rates, which would obviously limit occupancy, but to a level where staffing was available to support it. So we actually had a rate-led recovery. Hotels ultimately maintained higher rates at the cost of occupancy.”

Whatever the cause, though, growing expectations for lower occupancy hardly seems like a recipe for a healthy recovery, especially for one of the world’s great tourist destinations.

“If you’re a family of four, spending a week in New York City could cost you thousands of dollars. You might as well come for a day visit,” said Ariel’s Shkury. “In terms of tourism, [higher costs] prevent more people from coming here and staying here longer, and it also could prevent corporations from holding company retreats or conferences here.”

The cost issue has also been exacerbated by the migrant situation, which took many budget or lower-priced hotels out of commission for tourists.

“If you want a room in New York City, it’s harder to find economy hotels,” said JLL’s Davis. “You’ll have to go into a higher-rated hotel category, which is generally more expensive. And the absence of midscale and economy options has enabled owners of upscale hotels to charge higher rates. That’s the dynamic at play right now.”

Given the many obstacles facing hoteliers and hotel guests alike, Blackstone believes the best way forward is one where the powers that be remember that having a desirable, plentiful and affordable hotel base is essential for New York’s appeal.

“It’s an issue of economic development,” said Blackstone. “There’s a lot of focus on the need to develop affordable housing in New York City, and New York City needs a lot of affordable housing. But in order for neighborhoods to realize their potential — and I’m thinking specifically about East Harlem — it’s also important that the public sector be very much focused on what is necessary for balanced development.”