Overbuilding in Multifamily Today Means a Lack of New Units Tomorrow

The cliff drop in supply will be great for investors and owners — not so much for tenants

By Brian Pascus July 29, 2024 12:16 pm

reprints

We’ve all seen the famous Warner Brothers cartoon and know the outcome by now: Wile E. Coyote, supplied with overconfidence, inches closer and closer to catching the elusive Road Runner, who is always just one step ahead of his grasp, and just when he’s about to grab him …

The bottom drops out, the cliff opens, and the coyote plummets down into confusion and chaos.

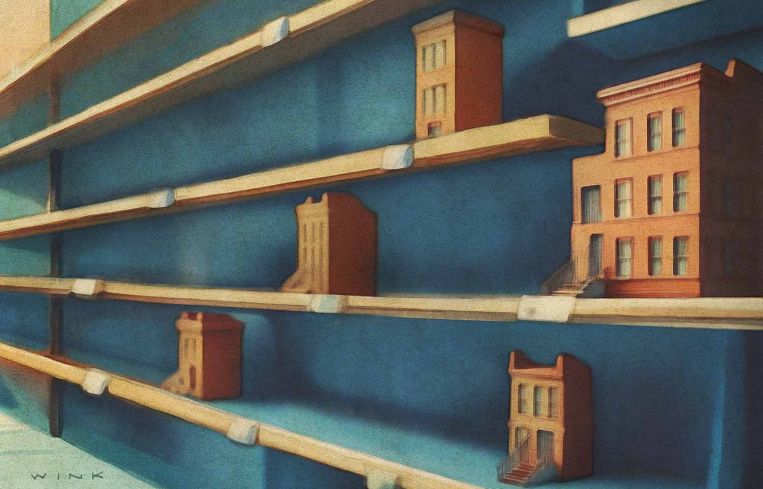

Don’t laugh yet, because this proverbial cliff in Looney Toons could be a good metaphor for the nation’s supply of multifamily housing.

A July report from Yardi Matrix, a commercial real estate data firm, found that new unit deliveries of multifamily apartments nationwide will drop from 560,000 units in 2024 to 350,000 in 2026, and fall even further to 328,000 in 2027.

“What happens after 2025 and in 2026 is there’s this cliff,” explained Doug Ressler, manager of business intelligence at Yardi Matrix and an author of the report. “Then you go back to your Economics 101 textbook: Demand continues to go up but supply goes down, what happens to the prices? I’ll tell you, right now, it will push the pricing envelope.”

Prior to the pandemic, a healthy annual rate of new national multifamily deliveries fell between 375,000 to 425,000 per year, but since immigration has surged in recent years, the ratio of deliveries to population growth has changed, according to Ressler.

For many investors involved in the multifamily sector, the thought of a sudden dearth of supply and subsequent upshoot in prices seems at odds with an asset class currently experiencing a fit of relative oversupply and tepid rent growth. This is to say nothing of strong indicators like increased demand, higher consumer spending, and a homeownership market that is all but unattainable for most Americans.

“It’s an interesting time in the multifamily sector because, in some ways, you have headwinds: low unemployment, so people are spending, the consumer is healthy and needs a place to live; mortgage rates went up fast and home prices rose fast, so rental prices are high,” said Kyle Jeffers, chief investment officer at Acore Capital. “And 2024 will be one of the highest deliveries on record. But then you have this dynamic where construction starts to completely drop off the table.”

Sam Tenenbaum, head of multifamily insights at brokerage Cushman & Wakefield, noted that construction typically has a two-year time frame, with any units built today delivering in 2026, and that the current pipeline of new entrants coming into the market is “pretty bare” in the forthcoming years, almost like an empty cupboard.

“We’re not starting many new units or getting them out of the ground,” said Tenenbaum. “With very limited starts, I’d expect to see that construction number fall even further from 500,000 to 300,000, and that dropoff is eventually going to translate into a decline in delivery.”

The price of scarcity

Rather than paint the macabre image of a steep fall off a cliff, others have characterized the impending decline in multifamily deliveries as a drought, or a sudden evaporation of supply.

“The stuff that’s finishing this year, and the new starts from 2025 to 2028, are dramatically diminished from where they were before,” said Kyle Draeger, executive managing director of multifamily capital markets at brokerage CBRE. He said the shift has made more developers say it’s both “hard to get a construction loan” and “hard to find equity for predevelopment.”

CBRE data found that new multifamily construction starts this year are already below 2014 levels — levels that had remained fairly consistent until 2019, and then zoomed into overdrive during the pandemic-era, high-demand, low-interest rate years of 2021 and 2022.

“We’re not going to hit zero [new starts], but it will give us a suppressed level that will likely drop our vacancy below long-term average, and that will be seen as an undersupply at that point,” said Travis Deese, associate director of multifamily research at CBRE. “It’s a big drop right now, you can describe it as a cliff, but it won’t be as dramatic as some people are portraying it.”

The lack of concern from some economists toward once and future supply of multifamily has largely to do with fundamentals: The average U.S. advertised rent increased 3.1 percent year-over-year (June 2023 to June 2024) to $1,789, while overall occupancy for multifamily stands at a healthy 94.5 percent, down less than 1 percent from where it was this time last year, according to Yardi Matrix.

However, even though the market is on pace to absorb 300,000 units this year, it’s still a far cry from the 600,000-unit lease-up rate the nation experienced in 2021.

“It’s sort of an interesting confluence of events: We’re coming off an all-time record of supply, we’ve had over 1 million units of construction [annually] for the last couple of years, but that number is starting to drop as we’ve come off that peak,” explained Lee Everett, head of research at Cortland, a multifamily owner and operator. “At the same time, fundamentals are strong, and, while you’ve seen vacancy increases and rent growth be slow in some markets, you’ve had general stability because the demand story has remained robust for the sector.”

The demand story has been a product of the pandemic, which saw construction ramp up as vacancy dropped to all-time lows in 2020 and 2021. Not only did Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell cut interest rates to near zero, but a national eviction moratorium kept consumers in their homes, slicing vacancy. Meanwhile, the dependable yields in a near-zero interest rate environment promised appetizing returns for investors in a multifamily sector that seemed utterly immune to the distress wrought across hotels and offices while COVID-19 was raging.

The combination of easy money and little supply juiced an appetite for the asset class. National multifamily rents started their unprecedented climb in April 2021, moving from just over $1,400 on average in 2020 to more than $1,700 by November 2022, where they’ve stayed ever since, according to Yardi Matrix.

Today, however, as the federal funds rate tops 5 percent and the 10-year Treasury sits at 4.2 percent, new construction starts for multifamily are down to levels last seen during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), while oversupply is choking rent growth from moving higher in most markets, according to Everett.

“What that means is, assuming it’s 30 months to construction, you’ll see a pretty big lull in 2026 in the supply pipeline,” he said. “That doesn’t mean no one will build again, there are still some permits out there, but in 2026 and 2027, and maybe even 2028, there should be a pretty sharp decline in those levels that we haven’t seen since right after the GFC.”

Nevertheless, not everyone in the industry views the drought of supply as a bad thing for the market. That’s mainly because as vacancy drops below the long-term average, rents will rise, in turn increasing values for owners, operators and investors.

“We wouldn’t call it a cliff — deliveries will peak at the end of this year, to about half a million, so if you go out post-2025, and into 2026 and 2027, it’s a pretty dramatic decrease,” explained David Reynolds, president of investment management at Mill Creek Residential, a CRE firm specializing in multifamily equity and credit.

“But if you look at historical averages,” Reynolds continued, “it’s more like 20 percent below where it’s been historically, which is still meaningful. So for an owner in the multifamily community it’s good, because you’ll be able to increase occupancy and push rents.”

Reynolds said that his firm expects rents to remain flat this year, jump up a little in 2025, and grow more than 4 percent in 2026 and 2027. With so much supply coming online in recent years, and so few homes affordable due to existing mortgage rates, multifamily operators have been able to maintain occupancy quarter-over-quarter, he said.

“It’s really just reflecting this strong level of demand and absorption,” said Reynolds. “You need to get above 94.5 percent on occupancy to get positive rent growth, in our experience, and above 95 percent to push rents. So we see brighter times ahead.”

A tale of two faces

If it seems like we’ve told two stories thus far about the state of multifamily, you’re right, because the asset class resembles the old Roman mythological figure Janus, god of beginnings and endings, entrances and exits, whose two faces each looked in opposite directions.

While all eyes have been cast on the impending drop, or drought, in supply, the asset class is presently experiencing a contradictory crisis: There is too much supply in many American markets.

“The deliveries of 2023 and 2024, in certain markets, are creating excess supply, you have more concessions, a little more vacancy, and maybe some decline in rents,” explained Acore’s Jeffers. “Austin has had really big new supply deliveries, and in other markets, you’re seeing rent growth decline, so I know the market is getting worse because rents aren’t growing quite as fast, and in other markets, like Austin, rents are declining.”

The present supply wave has been almost exclusively driven by the low interest rates of recent years that spurred new construction for much of the past decade. Units under construction in buildings with at least five units rose from as low as 154,000 a month in June 2010 to a peak of more than 1 million a month in July 2023, the highest level since 1973, according to Census and Department of Housing and Urban Development data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

Today, that same monthly average stands at 880,000 units. Many of those new unit deliveries are creating supply bottlenecks across Sun Belt cities, which garnered renewed traction from renters during the pandemic and have remained popular as rents have concurrently risen in the traditional coastal powerhouse markets like New York and Boston.

“The Sun Belt market is a bit saturated right now with deliveries over the next 24 months, as people are completing projects that were started with very cheap financing,” said Matan Kurman, head of originations at S3 Capital, a CRE lender. “We’re in a unique and interesting point in time with the Nashvilles, the Charlottes, the Miamis, the Fort Lauderdales, the Dallases. All the buzz cities in the Sun Belt are just at a tipping point, as for the next two summers, there’s oversupply,” Kurman said.

Amid a burst of supply that’s pushing down rents, owners and operators are also dealing with increased marketing expenses (due to more competition), surging operating expenses (due to inflation), and the apparent abandonment of Jerome Powell’s December 2023 pledge to cut interest rates sometime in 2024.

“The general view would be the Fed will cut rates in September, or two times this year, and you’ll see a return of marginal affordability to rightsize this to a degree, but for now its something some owners might be kind of trapped in,” said Brad Dillman, chief economist at RPM Living, the multifamily management firm. “It’s a challenging environment for them.”

To make matters worse, there’s the uptick in distress across commercial loan obligations (CLO) and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) backed by multifamily properties, many of which were financed with floating-rate debt under the assumption that rates would stay low and their debt service would stay low as well. That’s an assumption that’s been turned on its head, as the fastest interest rate hike in 40 years has trapped investors into negative leverage, as exit cap rates are lower than interest on their debt.

Unlike the vast majority of multifamily projects financed through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, single-asset, single-borrower commercial mortgage-backed securities are typically 10-year loans, and have seen their distress metrics jump from 2.6 percent at the start of the year to 7.4 percent, according to CRED iQ, a CRE data research firm. CRE CLO distress has hit a peak of 10.3 percent this month, according to CRED iQ, as higher interest rates have taken a hammer to debt service coverage underwriting.

“They can only raise rent so much to really cover that surge in annual interest costs, so it’s actually crushing these loans,” said Mike Haas, founder and CEO of CRED iQ. “A lot of these loans were issued in 2020 and 2021, when cap rates were low, interest rates were low and valuations were high, when so much issuance was making up for the lost year during COVID.”

If these reports from the front lines seem scary, it’s important to remember that, like all aspects of economics, one piece of bad news usually begets a better outcome for metrics on another end of the spectrum.

TJ Parker, lead researcher of data analytics at Bell Partners, admits oversupply exists, but argues the long-term, secular tailwinds for national multifamily markets remain firmly intact. To wit: Immigration has been robust, and new arrivals (both legal and undocumented) have bled into gateway and Sun Belt markets; demand remains strong due to healthy job and wage growth; and corporate relocations are prioritizing the oversupplied Sun Belt cities due to their cost of living and ease of doing business, generating healthy absorption rates for even the most oversupplied markets.

“Those advantages, those tailwinds, they don’t go away,” said Parker. “That’s what’s needed for renter demand in the long run. The oversupply this year is a temporary challenge.”

A fortunate future — for some

While oversupply might be a temporary challenge, in terms of rent growth and values, the impending cliff-drop in supply is likely to make renting a long-term challenge for the average American.

Due to the baby boomers aging out of their homes and many then looking to rent in their twilight years, and simultaneously a growing cohort of indebted millennials and Gen Z’s finding themselves priced out of owning a home altogether, executives like Doug Faron, founder and CEO of Shoreham Capital, believe the intrinsic demand baked into multifamily housing will spur rent growth far into the future.

“There’s not a slowing down in the demand for housing, especially rental housing. Big segments of the population that would normally own, millennials and baby boomers … will be the reason there’s demand for rental housing,” said Faron. “And, two years from now, as all this stuff gets delivered and no new construction starts, you’ll see outsized rent growth.”

To find what the future of many U.S. markets may look like as supply evaporates, look no further than New York City, which saw its rents grow seven times faster than wages in 2023, according to Zillow.

Construction citywide basically halted following the June 2022 expiration of 421a — the tax abatement that gave developers an incentive to build both affordable and market-rate housing — as well as the state’s 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, which limited rent hikes on existing supply and removed tens of thousands of stabilized rental units from the landscape out of concerns that landlords would turn them into more expensive market-rate housing.

“You think you have a housing stock problem now, wait till no one puts a dollar into these buildings and the violations pile up and repairs pile up — you have a ticking time bomb in New York City,” said Yosef Katz, principal at Atlas Realty Group. “On the free market, rents will rise and the stabilized stock will completely deteriorate.”

The rise is already on: Since 2019, average U.S. rents have grown 30.4 percent, while wages have grown 20.2 percent, and rent growth has outpaced wages in 44 of the 50 largest U.S. metro areas, according to Zillow.

As the supply cliff approaches, these rising rents now forecasted have turned owners and investors giddy, as they recognize the long-awaited relief from this current era of oversupply will tilt rents, and therefore values, upward.

“We remain very bullish on residential broadly, and multifamily is ascendant in it,” said Faron. “Now is a great time to buy existing assets and buy at replacement cost, stuff with operational value-add. We just think it’s an interesting place to play.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com