Whatever Happened to ‘Smart Cities’?

They didn’t go away — it’s just more about the buildings in the cities now

By Philip Russo June 18, 2024 10:00 am

reprints

In May 2020, the smart city concept appeared to have been dead and buried when Sidewalk Labs ended its collaboration with the City of Toronto to create Quayside, a data-infused, sustainability-focused experiment in urban living.

Killed by a combination of Sidewalk Labs’ opaque vision for the techno-neighborhood, conflicts about public funding of the built world over enhancing the natural environment, privacy concerns, and the 2-month-old COVID-19 pandemic, Quayside’s death seemed to herald the demise of the smart city. In December 2021, Alphabet folded Sidewalk Labs, its urban innovation arm, into Google.

The smart city may still be 6 feet under, but there remain some instances where cities, mostly in top-down autocracies such as China and some Persian Gulf states, see data-infused metropolises as a social good rather than a potential evil.

Smart cities are generally defined by their capacities to collect data via technology and then to use that data to improve operations as varied as transit systems, power plants and jails.

In 2022, Digi, an internet of things company, listed Dallas, Chicago, Austin, Seattle, Charlotte, San Francisco, Washington, Boston, Pittsburgh, Boulder, San Jose and New York City as “smart cities.” Today, the levels and effectiveness of smart city innovation in the U.S. are less than massive, particularly given that impact from COVID as well as inflation and higher interest rates since 2022.

If a spark of the smart city concept remains in the United States, its rekindling will require the continued growth and interconnectivity of proptech-supported smart buildings, said Troy Harvey, CEO of PassiveLogic, a Salt Lake City-based platform that uses technology to make commercial, industrial and multifamily buildings more energy efficient.

“If you look at what a city is, there’s maybe three large parts we could talk about, the biggest component of which is buildings,” said Harvey. “You can’t talk about smart cities without having smart buildings. The second piece is there’s a bunch of infrastructure in cities, like [energy] grids and all the things that operate in the city such as traffic lights. The third piece is transportation.

“So there’s a bunch of different lenses by which you can measure the proportion of those. You can look by energy count, or by land use, or by dollars. Buildings are by far the biggest portion of all three. So why are we focused on that built environment piece? Because it is the biggest player in dollars, energy and use.”

Although the smart city may be stalled in the U.S., overseas the movement is seeing more traction with the tech world.

One example is Stockholm-based ProptechOS, which sees the smart city as an ecosystem for sustainability, quality of life, and productivity, with buildings intelligently interacting with each other and people.

Founded in 2019 by Erik Wallin and Per Karlberg, ProptechOS seeks to solve real estate challenges with interconnected products that teach themselves — and talk to each other.

“We have this vision where one smart building is asking for resources from another smart building, and communicating with other actors in a smart city,” Wallin said in a company statement. “To make this a reality, we need more buildings to join. And this is where having a common language is key.”

To that end, ProptechOS created an open-source platform called RealEstateCore. The platform describes the data within the buildings that the company operates, as well as the management, storage and sharing of this data.

“We need these kinds of solutions to be able to get our buildings talking to each other and to create the kinds of smart solutions we want to create without being locked into somebody else’s system,” Peter Östman, communication director at Vasakronan, a leading Swedish property firm that helped found ProptechOS, said on the startup’s website. “The ProptechOS operating system lets us real estate owners maintain data freedom while making it easier to realize the fullest potential of our smart building visions, both now and as new ideas and opportunities emerge in the future.”

Back in the U.S., having founded PassiveLogic in 2016 and received venture capital funding in 2020, Harvey compares building connectivity development and environmental impact to that of autonomous vehicles.

“Buildings are about twice the energy consumption of vehicles,” said Harvey. “If you think about the vehicle market, we’re making this transition from gas to electric right now and that has some energy savings attached. Of course, that leads to some of the climate issues we’re all trying to solve now. Autonomy doesn’t really change the picture that much from gas to electric. You go from electric to autonomous electric — maybe it gets slightly more efficient, but not substantially.”

However, because office, industrial and multifamily buildings use so much more energy than vehicles, they are a bigger carbon reduction target for proptech and a company like PassiveLogic, he said.

“If you can just control the tweaking and tuning of what we already have without big retrofits, new equipment, breakthroughs like heat pumps and whatnot, we can save 40 percent of the energy in the built environment,” said Harvey. “That’s not like making gas cars electric. That’s removing all transportation from the planet in terms of energy use. So it’s the single biggest opportunity.

“We saw this transformation happening around autonomous vehicles, and we said, ‘Oh, well, this is far more valuable, far more applicable, and a bigger market in buildings than it is in vehicles.’”

Admitting that the term “smart cities” itself is nebulous, and aside from the environmental impact of buildings, Harvey said that we have to think of the built world as being “redistributed.” While not as many people have returned to office buildings, the workers in those buildings have been redistributed to their homes or other nontraditional office sites.

“Buildings, as an infrastructure marketplace, is way behind technologically other industries, and they know that they have to shift,” said Harvey. “What you’re probably going to see is this start from the building side and then bubble up, rather than something down from the city side down. Because I don’t know if that is practical or functional.”

An example of such technological innovation can be found in the transformation of the telephone industry from a monopoly, AT&T, to the “Baby Bells” and succeeding phone companies, he said. AT&T would never have invented the mobile phone we didn’t know we wanted or needed, but Apple did.

“Apple created the device that we all wanted, in order to change the model of how [telephony] all worked,” Harvey said. “And, until that device was there, it didn’t matter how we all imagined this wireless, connected world. That was sort of imagination. So I think the city example will take that same path and does naturally because the buildings fundamentally need to have a technology platform that these owners can operate off.”

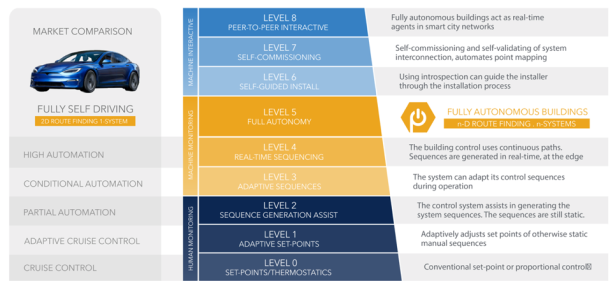

For Harvey, an even more revealing comparison to smart buildings and cities is the ongoing development of autonomous vehicles.

“The reason we think it’s a really important construct is that everybody in the vehicle industry, when they talk level-through autonomy, they all know what each other is talking about,” said Harvey. “In buildings and cities we just say ‘smart cities,’ ‘smart buildings.’ But what the heck does that mean? What levels of autonomy do is set a standard for what is smart and how smart it is. So, in the connection between the vehicle world and the building world, it turns out that’s actually a one-to-one mapping.”

However, that technological mapping of autonomous buildings faces similar challenges to autonomous vehicles moving from manual control to full autonomy as has been long promised amid ongoing experimentation.

“In both cases, it’s the exact same algorithm,” Harvey said. “It’s a thing called PID [proportional integral derivative] that runs both your cruise control and your thermostat.”

It remains to be seen if the private and public sectors are smart enough to turn up the heat on smart city development, while cooling off global warming and other urban challenges.

Philip Russo can be reached at prusso@commercialobserver.com.