There’s a Race On for Restaurant Space in the U.S.

Inflation and the pandemic have wrecked some chains, giving insurgent dining concepts a chance to feast on the leftover real estate

By Patrick Sisson May 20, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

With the ever-changing nature of dining trends and strip mall occupants, it might be tough to notice. But there’s a battle for restaurant retail space taking place in commercial corridors across the U.S. right now — and the insurgents are gaining.

“Obsolete, older, fast-casual concepts are struggling,” said Matt Hammond, vice president at Coreland Companies, a Southern California brokerage that specializes in retail leasing. “As those spaces become available, newer, emerging concepts that have capital and technology are excited for the opportunity to get some great real estate that has been occupied for the last 10 to 20 years.”

Shaped by rising costs of business, including higher wages and more expensive energy and food, the post-pandemic restaurant landscape has bifurcated.

A core group of popular chains like Cava — buoyed by streamlined operations, mobile- and pickup-first layouts, and better operational and labor performance — have seen their fortunes rise with expansion and new locations. They have the capital and revenue to reinvest in efficiency, employee training and even automation — Chipotle has tested a robot that makes guacamole. So far this year, JLL has recorded roughly 2,400 new restaurant openings announced in the quick-service and fast-casual spaces, an acceleration from recent years, according to senior retail research analyst Keisha Virtue.

Losers, who continued to rewrite their menus to compensate for a challenging inflationary environment, have hit the point where raising prices drives away customers, creating a downward spiral that leads to lower revenue, and, eventually, to shuttering locations. Revenue Management Solutions, a restaurant consultancy, found quick-service restaurant prices rose 2.6 percent annually in April. Many big brands have recently closed locations or announced closures, such as Red Lobster, Applebee’s, Denny’s and Boston Market, the last of which went from 300 locations at the start of 2023 to a few dozen today.

In many cases, the shuttered locations get picked up by the winners as part of their expansion. When Corner Bakery began closing sites over the last few years amid a bankruptcy, individual locations were getting up to four proposals from fast-casual chains looking to expand, said Hammond.

“We’ve seen cash flow for struggling restaurants decline anywhere from 30 percent to 50 percent last year versus pre-pandemic,” said Joseph McKeska, principal of dining-focused A&G Real Estate Partners. “The pricing power has started to wane, and they’ve just hit the ceiling in that respect.”

Consumers have also struggled, said McKeska, and ominous economic statistics, such as rising car loan and credit card delinquencies, suggest added stress that will hit restaurant operators moving forward.

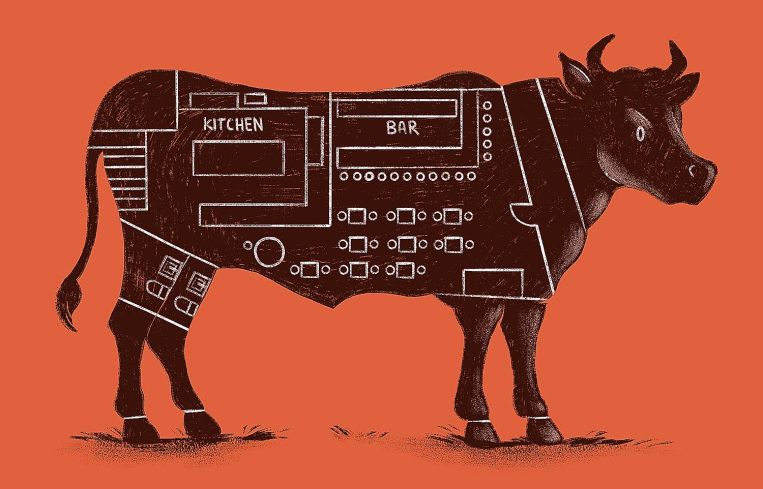

The restaurant industry’s response has been rapid evolution. This includes delivery-only models, a focus on pickup and delivery, expanded outdoor dining options, different revenue streams from ghost kitchens, smaller footprints, and more focus on technology to drive down labor costs and increase efficiency via app-mediated ordering and automation. Chick-fil-A, for example, is testing an elevated drive-thru concept and a new walk-up digital-focused concept in New York City.

This has been an era of scrappiness, said Paul Pruitt, principal and founder of New School, an L.A.-based restaurant consultancy. “If the industry has any silver lining from COVID, it facilitated and necessitated a lot more ingenuity,” Pruitt said.

The size of new spaces might be one of the more immediate impacts. JLL found that 68 percent of restaurant deals in the first quarter were for spaces under 2,500 square feet. Even McDonald’s is getting in on this undersizing trend with its new beverage-focused CosMc’s spinoff.

Chains have tried to re-engineer their business models in the face of higher operating expenses, including being more selective about what markets they enter, according to Stephen Cohen, a lawyer with a national practice representing restaurants. There’s extreme caution in the industry, with many restaurateurs second-guessing their own growth strategy, Cohen said.

“It is really sending everybody back to the drawing board to figure out if they can reverse engineer and build their units for cheaper,” he said. “If food costs rise, you can raise your menu prices. But, if you sign a lease, you’re stuck for 10 years. “

While restaurant rents for the most part haven’t surged in recent months, the current massive market shift has placed more restaurants in direct competition when seeking to acquire real estate. Office is suffering, meaning downtowns and central business districts remain less attractive. Development of mixed-use, office-centered projects in all markets — which typically include plenty of space for restaurant expansion — has slowed.

Mall owners and operators want more independent and regional brands to diversify their offerings and keep consumer interest, a preference that pits a smaller number of restaurants against each other. The costs and risks of building new restaurants mean companies seek to avoid ground-up construction and prefer to repurpose older spaces, said McKeska.

Pandemic-era shifts toward hybrid and remote work have also generated more demand for suburban and rural expansion, ramping up competition for limited space in secondary and tertiary markets, said R.J. Hottovy, head of analytical research at

Placer.ai. Pad sites — free-standing properties in front of shopping centers — and unanchored strip sites have proved particularly popular for coffee chains and quick-service restaurants alike.

The boom in drive-thrus means smaller restaurant buildings overall, but larger outdoor spaces for operations to accommodate more car lanes. That’s accelerated the growth of drive-thru-oriented coffee chains, like Dutch Bros (which is set to open 150-plus stores this year), 7Brew, PJ’s Coffee and Scooter’s Coffee, which all benefit from automation and low labor costs, and tend to concentrate in the same exurban spaces where car ownership and remote work overlap.

The explosion of new coffee competitors highlights a larger dynamic: Franchisors seek to zero in on emerging brands and aggressively expand, while established, larger brands, especially in the quick-service space, are in “hunker-down” mode and are fortifying their footprints, said McKeska.

The areas where growth has taken root, not surprisingly, follows households: Southern and Southeastern cities in Texas, Florida and the Carolinas, which have seen growth in both population and household income, have been targets for operators and restaurateurs. But even states and cities typically written off due to high costs and burdensome regulations have seen increased interest and growth.

California, for instance, has been buffeted by a recent law mandating a $20-an-hour minimum wage for workers in the fast-food industry plus some of the nation’s highest real estate costs. Yet the state still sees significant openings. Coreland Companies’ Hammond points to chains like Urbane Cafe, Kebab Shop and a pizza chain called Slice House, which is aggressively expanding from San Francisco to San Diego, pursuing second-generation sites from chains on the way out.

Deal volume spiked in 2022, Hammond said, as California restaurateurs pursued a flight-to-quality strategy around new sites. Things have slowed recently because there aren’t many such sites left. Lots of restaurants remain ready to grow, waiting patiently for more struggling sites to close.

“Labor and rent, to a great extent, is extremely challenging here,” said Pruitt, the L.A. consultant. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t make money.”