Why Grocery-Anchored Retail Keeps Drawing So Much Attention

Institutional investors are in on the act now, and the approach is even having a halo effect on residential development

By Patrick Sisson May 27, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

There are few certainties amid an uncertain economy. But, for consumers, a regular trip to the grocery store tends to be a sure bet. That regularity has placed grocery-anchored retail in rarefied company among commercial real estate assets. Just as consumers’ need for these setups grows, investment is forecast to grow as well.

“They’re now getting snatched up by the institutions, whether it’s REITs or private funds,” said Cole Perry, senior market analyst at Altus Group, a commercial real estate intelligence company. “They perceive them to be recession-proof. They are high foot traffic, they’re easy to optimize, and they’re fairly standard in their format.”

Stable amid wider uncertainty, grocery-anchored retail has benefited from the tailwinds in shopping and consumption patterns that seem invulnerable now despite previous talk of a retail apocalypse. These are jewels amid an asphalt-covered commercial landscape. Of the nearly 140,000 neighborhood and community shopping centers nationwide, which cover about 4.4 billion square feet of retail space, just 8,350 have grocery stores as anchor tenants, with most built before 2000.

Though fewer such locations are trading at any point since 2020, Perry wrote in an article for Altus, “elevated in-person spending is working to the advantage of existing institutional owners.” And investment sales activity may start to accelerate in the second half of this year. While last year saw investment volumes in grocery-anchored retail hit a low point, sinking 54 percent year-over-year to $7.5 billion, per JLL, in 2024 the brokerage anticipates an acceleration “supported by robust investor demand.”

The pandemic made grocery an essential sector of the economy (literally), and the corresponding reopening rebound saw foot traffic spike. Population growth in the suburbs during the pandemic generated a need for new grocery stores and development. Digital grocery sales have even benefited grocers and big-box stores: 43 percent of online sales are pickup, and larger stores and chains have grown their own in-house fulfillment and delivery capacities.

Even the current bout of inflation keeps shifting more shoppers, and their dollars, from dining out to dining in. Most grocery stores operate on sale-percentage leases, so when the environment favors more shopping, they do really well, and when it doesn’t, they still generate a solid base rent. Foot traffic data from analytics firm Placer.ai showed visits to grocery stores last year outpaced pre-pandemic levels, rising 2.6 percent from 2019.

“In terms of the current state of the center, they have become stronger than they did coming out of the pandemic, because they have been doing so well,” said Mark Bratt, CEO of Westwood Financial, which has 125 grocery-anchored retail sites in its portfolio. “They continue to hold their value, with excellent cash flow and excellent rent growth.”

Much like restaurants, the bigger independent grocery stores, usually defined as expanding regional chains, have been growing their customer base and increasing their performance, said Altus Group’s Perry.

Florida-based Publix has been expanding in the Northeast, HEB is growing in Texas, and Hy-Vee is expanding in Iowa — and all have all been eating more and more market share. The biggest expansion story of last year was discount chain Aldi, which opened 109 new stores and acquired 400 Winn-Dixie and Harveys locations in the Southeast. The proposed merger of giants Kroger and Albertsons, which currently faces delays due to federal antitrust scrutiny, isn’t welcome in the grocery center investment community, said Bratt, since it likely will lead to store closures.

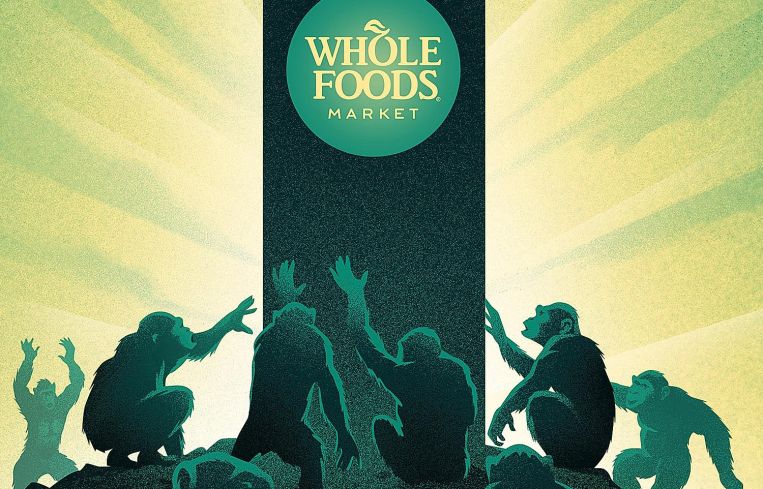

Other operators have seen the success of Trader Joe’s, which packs significant sales within smaller footprints, and set off on a similar course. As investors increasingly favor smaller-format stores, Perry said the actual average transaction size for grocery-

anchored real estate, in terms of cost, has been dropping, since institutional money favors high-traffic, small-footprint centers. Whole Foods in March announced a series of smaller-footprint stores, which analysts believe can help the grocery chain draw family shoppers looking for packaged meals, tap into and widen owner Amazon’s delivery network, and make beachheads in newly gentrifying urban markets.

“It’s adaptation,” said Perry. “It’s adapting to keep the same type of customer but in a different physical format.”

Stores have also amped up their services and amenities, said Derek Wyatt, managing director at real estate consultancy RCLCO. On the pedestrian end of this increase are more efficient delivery and pickup resources as well as a wider variety of freshly packaged foods. At the higher end, a new location of the upscale Gelson’s Markets chain in West Los Angeles allows shoppers to kick back in a new restaurant and bar as personal shoppers complete their purchases for them.

As grocery operators have shifted, so has the symbiotic retail around them. Landlords have become much more sophisticated when it comes to finding new tenants by using technology such as location-based analytics and cellphone data to better track foot traffic and draw a sharper picture of shopper demographics. Shopper demand has shifted tenant mixes toward more service-oriented stores and new food-and-beverage locations.

And other retail loves being near a grocery store. Westwood’s Bratt said his firm currently has a 97 percent retail lease rate at its grocery-anchored centers. Altus data shows grocery-anchored retail has higher occupancy and less lease turnover than sites that lack grocery stores. With limited new development, per the recent JLL report, conditions remain favorable for strong rent growth in retail.

“Grocery-anchored retail has about 5 percent available space compared to common neighborhood centers not anchored by grocery, which is more like 20 percent,” said JLL senior research analyst Keisha Virtue. “Obviously, people kind of want to move into centers that do have some grocery anchor because the foot traffic is ever so much higher and better.”

Grocery even has a halo effect on residential properties. A new RCLCO report finds that in projects where apartments are built above retail, the grocery element actually generates a 5 percent premium for apartment rents. With a Trader Joe’s, the premium jumps to 5.6 percent, and with a Whole Foods it jumps 6 percent.

It’s even driving redevelopment. Grocery-anchored sites tend to have a lot of parking, which makes it easier to not only demolish and rebuild, but also to add housing while including grocery and retail at ground level. In Santa Monica, developer Related California entered into a deal with Vons, a local grocery store owned by Albertsons, to redevelop a store site into a 280-unit apartment development anchored by a brand-new Vons. Kimco, North America’s largest public owner and operator of grocery-anchored shopping centers, plans on a spate of similar redevelopments across its portfolio, and has entitlements for nearly 10,000 apartments to be built on such sites.

“What could possibly derail grocery?” said Westwood Financial’s Bratt. “The only thing I can think of is really intense inflation or a pandemic. And, even then, maybe instead of going to Kroeger, people would go to Walmart. The industry for the most part is in really good shape.”