New York’s $237B Budget Covers Growing Health, School Costs — For Now

By Abigail Nehring April 22, 2024 8:23 pm

reprints

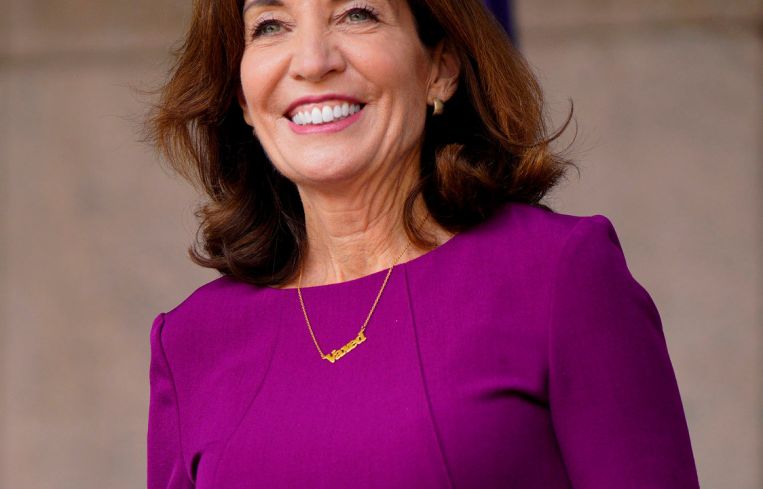

New York State lawmakers enacted a $237 billion dollar budget Sunday. It grows the state’s spending plan by a half-a-percent from last year, after adjusting for inflation. And it covers the growing cost of Medicaid, provides billions to deal with the city’s migrant crisis, and includes what Gov. Kathy Hochul described as a “transformative” housing deal.

It also leaves the state with about $19 billion in reserves — enough to keep the government open for about two months. Hochul benchmarked 15 percent of this year’s operating funds for the state rainy day fund, describing this amount as the “gold standard.”

But lawmakers kicked some big ticket items down the road and the enacted budget leaves the state with an estimated future structural deficit north of $16 billion, according to the nonprofit budget watchdog group the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC).

Medicaid costs are growing at a rate of about 7 percent annually, faster than other parts of the budget, and that’s cause for concern because the state might not have enough cash in the future to foot that bill, said Patrick Orecki, director of state studies at the CBC.

“Frankly, there isn’t a tax base that’s going to keep up with that,” Orecki said. “So you’re either going to be in a position of constantly raising tax rates or crowding out spending in every other area of the budget to accommodate Medicaid.”

Legislators adopted a mechanism to generate about $4 billion annually from state and federal funds to cover its Medicaid bills for the next three years, but the details will remain murky until New York’s budget office publishes the financial data along with the budget bills lawmakers passed over the weekend.

“Without financial plans, we don’t know what the dollar amount is, or what the timing of the spending is,” Orecki said.

The legislature also refused to remove the state’s “hold harmless” provision, which would have reduced education costs by dropping the practice of keeping school district funding the same each year.

Sparing schools from the governor’s proposed cuts was a “victory for students throughout the state,” State Sen. Michael Gianaris said in a statement.

The CBC, however, argued that the provision was a “common sense” method to curb future budget deficits. As it is, public schools got a boost of about $1 billion compared to last year’s budget to a total of $35.9 billion.

While there’s still a lot of unknowns in the budget, what we do know, according to lawmakers’ remarks and Hochul’s Monday morning announcement, is that the state will spend about $4 billion more than Hochul proposed at the start of the year.

That’s in part thanks to the budget director’s rosier-than-expected economic outlook in March after the state’s accountants reviewed updated tax receipt data.

And the spending closes last year’s $4.3 billion budget gap without raising taxes on businesses or personal income.

It does that despite an effort from lawmakers in both houses of the state legislature to raise personal income taxes on people in the top bracket who make at least $5 million annually.

Hochul put the kibosh on that, and her position was buoyed by the unexpected spike in state revenue from high-income earners in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those funds allowed the state to prepay some of its future expenses.

Plus, personal income tax and corporate tax increases enacted in 2021 will continue flowing into the state’s coffers for a few years, but that law sunsets in 2027, creating another structural imbalance watchdogs have their eye on.

All this makes for a mixed bag from a financial planning perspective, according Orecki.

“Those prepayments will eventually be exhausted, so the way that they are contributing to lowering gaps will eventually go away,” Orecki said.

As the ink was drying, the budget bills clocked in three weeks late this year, though that’s pretty much par for the course in New York, where the fiscal year begins on April 1, unlike just about every other state in the nation.

Even with the delay, hacks to the state’s computer systems and worries about future deficits, lawmakers still praised what eventually got passed.

“As is always the case, we did not get everything we wanted in this final budget, but it represents progress for the people of New York across many important areas,” State Finance Committee Chair Liz Krueger said in a statement.

Abigail Nehring can be reached at anehring@commercialobserver.com.