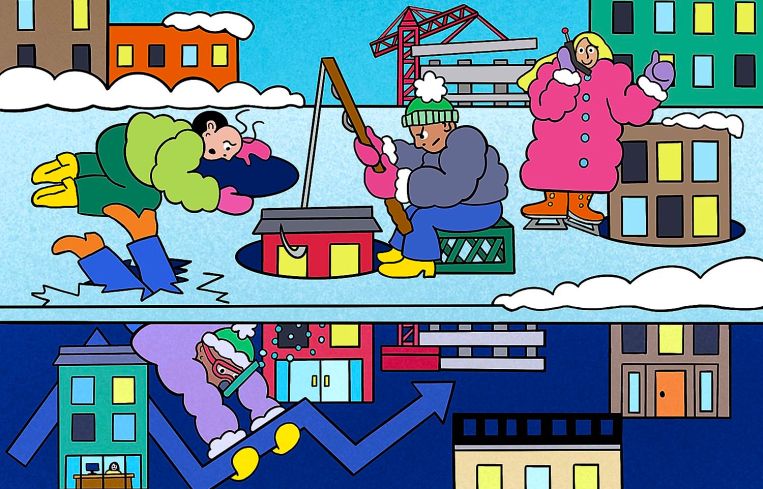

Into the Wild: Is 2024 the Year the Ice Breaks On Commercial Real Estate?

Experts assess CRE capital markets heading into 2024

By Brian Pascus November 13, 2023 6:00 am

reprints

As 2023 draws to a close, business leaders across the commercial real estate landscape can only offer weary assessments on whether capital markets will recover from one of the most disruptive years in recent memory.

“The markets today are very dynamic, and that’s probably the most diplomatic word I can use,” said Bill Fishel, executive vice chairman of Newmark. “There’s a scarcity of capital, there’s a scarcity of time, and there’s a scarcity of resources at the corporate and individual level.”

Others offered a less diplomatic assessment.

“There’s obviously a big dislocation,” said Doug Middleton, vice chairman of CBRE’s investment property group. “Essentially every property type is being impacted.”

By now the familiar culprits of this volatility have long been identified:

To stave off soaring inflation, the Federal Reserve has engineered the swiftest interest rate increase in four decades. Three years after the nadir of COVID-19, offices nationwide are roughly half empty, while a widespread housing crisis is pushing multifamily rents into unchartered territory just as supply declines in larger metropolitan cities. Inflation remains persistent, impacting the cost of construction and labor, to say nothing of consumer spending and investment patterns. And if that weren’t enough, this past spring’s regional banking crisis has drained liquidity from the system, putting present and future loan terms into purgatory.

“Our policymakers are a bunch of morons, and all they’re doing is screwing up the whole market,” said Bob Knakal, senior managing director at JLL. “And I think they’ll continue to do that, so that’s problematic.”

So, considering the myriad issues facing CRE, the question now stands: Is 2024 the year the ice breaks?

“I think 2024 is when the ice breaks. That’s when we begin the process of facing the reality of having to re-equitize the sectors and to address, across the board, the shift in the new interest rate paradigm,” said Scott Rechler, CEO of RXR. “There’s been a little bit of a delay in that happening as rates continue to move.”

Interest rates hold the key to the future, according to Rechler and others. In recent months, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and his board have opted to pause hiking the benchmark federal funds rate, leaving it unchanged at between 5.25 percent and 5.5 percent. But Powell has indicated one more rate hike is on the horizon before we leave 2023 behind, with all bets off as to how he will approach inflation in 2024.

This nebulous forecast has helped cripple lending. CRE debt origination volumes declined by 52 percent year-over-year by July, with the number of lenders dropping by a third, according to a national market report from CBRE earlier this year.

Office transactions, once the beacon of industry health, barely hit $25 billion through the first three months of 2023, compared to $40 billion in transactions in the fourth quarter of 2021 alone, according to a recent national report from Yardi Matrix.

“Without transparency on values, and not having transaction activity, it’s given owners and lenders reasons not to face the reality of what they are because there’s not enough clarity,” explained Rechler.

Even more troubling, yields on the 10-year Treasury, which is used to price most CRE transactions, touched 5 percent in late October. To offer some perspective on how unsettling that is, consider this: Yields on the 10-year Treasury didn’t rise above 2 percent between August 2019 and March 2022.

Alfonso Munk, chief investment officer of the Americas at Hines, described interest rates as “the fuel that makes real estate work,” and expressed doubt whether the market can process a world of permanently higher rates.

“I’ve been doing this for 26 years, and it’s been too rapid of an increase,” Munk said. “People were too addicted to the low interest rate environment for 15 years. A lot of the players didn’t see the pre-GFC environment where interest rates were high. So people are having a hard time adjusting to this world.”

Knakal, however, dismissed any widespread concern around rates, even while acknowledging that he can’t predict their next direction.

“Historically, over the past 50 years, the average 10-year Treasury has been 5.4 percent,” he said. “Even at elevated levels we’re at today, it’s not high by historical standards. So lending will get more affordable once bank spreads come in.”

Rechler agreed with this take, and emphasized that both interest rate clarity — and stability — is the key to CRE’s performance in 2024.

“As transactions start to occur, valuation will be crystallized, and, with those valuations crystallized, it will force the acknowledgement [of pricing], it will force banks to write down their loans, and owners to write down their equity,” he explained. “And I think that will start accelerating [recapitalization].”

Office uncertainty

That said, even with some future interest rate clarity, it’s unclear how the recapitalization of a severely depressed office sector will unfold.

National office vacancy stands at a whopping 18 percent, with major metropolitan centers like Houston and Seattle experiencing vacancy rates of 25 percent and 22 percent, respectively, according to Yardi Matrix.

“Office will continue to recover from a psychological perspective, but will continue to deteriorate from a financial perspective,” said Shlomo Chopp, managing partner at Terra Strategies. “People have it totally written off, but we’re seeing there’s still a place for office.”

Chopp said the asset class is desperately in need of innovation, and that tenant improvements pushed by newly empowered employees (and acceded to by nervous employers) will continue to increase construction costs into 2024. As rents remain depressed from the newfound permanency of hybrid work, a troubling financial equation will emerge for many sponsors.

“The income side won’t keep up with the expense side, and therefore we’ll see an adjustment in revenues, even for the best offices,” he said. “For those offices that aren’t the best offices, [those] will just see a lot of people walk away from commodity office.”

Hines’ Munk was insistent that it will take longer than just 2024 for the office sector to recover. He noted that it took until 2023 — three full years — for the macro effects of the work-from-home phenomenon, an oversupply in existing office space, and an ugly revelation of lower-quality assets to make themselves felt across the nation.

“It took three years for the problem to occur, so it will take three years to solve,” he said. “I don’t see the office sector recovering substantially until 2026.”

Knakal agreed that the office sector has “another two or three years to go,” and dismissed the idea of conversions providing any long-term saving grace. The longtime CRE sage noted that prices for existing buildings are so low that the cost to demolish is less than overall land values, making most conversions impractical.

“I think you might have more buildings demolished than converted [in 2024],” he said.

However, not everyone was doom and gloom about the future of office. Newmark’s Fishel said measurable data regarding the efficacy of hybrid work versus in-office collaboration will finally become available in 2024 after two years of relative post-pandemic stability, which will help determine to what extent work habits have permanently changed, either for the better or worse.

“I do believe office has a sustainable place in the American economy, and 2024 will be the year when these different paradigms play out,” Fishel said. “There’s something basic and fundamental and human about interaction. You can’t give a hug or high-five over the phone.”

One of the nation’s premier CRE developers, on the other hand, isn’t so sure that investors in the asset class can recover from the current distress, due to having their equity wiped out.

“They got hit by the one-two punch there: They have demand that’s declined by at least 50 percent for their product, and they got hit with high interest rates,” said Don Peebles, founder and CEO of The Peebles Corporation. “They are in a very, very precarious situation. And there’s not a lot of solutions out there.”

Multifamily mutant

Things are more amorphous on the multifamily front, with the asset class likely to keep its hall of mirrors appearance through 2024 and beyond.

Fundamentals like rents and supply patterns have remained robust through the dislocation, creating the appearance of stability, but the sturdy foundation of multifamily lies embedded over capital markets sands that can shift and crumble upon every interest rate uptick.

National average monthly rents for U.S. multifamily housing were $1,722 in September, while occupancy held steady at 95 percent, according to Yardi Matrix. Supply has been largely unconstrained in Southern and Southwestern markets. A nationwide housing crisis amid 8 percent mortgage rates means demand for rental units is expected to continue, juicing supply even more.

“The fundamentals are so strong, and with the relatively low supply of housing, rents are now up, so the demand drivers are very secure,” said Shimon Shkury, president and founder of Ariel Property Advisors.

But there’s more to commercial real estate finance than merely supply and demand.

As the yield on the 10-year Treasury reaches 5 percent, multifamily property values have dropped as the cost of capital to fund acquisition and construction debt has increased in turn.

Moreover, capitalization rates — a property’s net-operating income divided by its purchase price — have also risen steadily, as cap rates are a direct derivative of borrowing costs (when interest rates are low, cap rates fall lower, and vice versa), further hammering the value of buildings.

Cap rate changes are the crux of the issues surrounding multifamily properties, many of which were financed three to five years ago when cap rates were at 3.5 percent and the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) stood at less than 1 percent between March 2020 and July 2022.

“The cost of capital has definitely gone up,” said David Reynolds, president of investment management at Mill Creek Residential. “You look back when SOFR was basically 25 basis points, and you put 300 to 375 basis points on top of that, the interest rate on construction was 4 percent or less. Today it’s more like 9 percent.”

Perhaps most alarming to investors and developers is the consensus that no one should expect to grow their way out of this transfigured multifamily marketplace.

“Now there’s so much supply coming online, rents are flattening, and expenses are growing faster than 3 percent,” explained Adam Aultz, managing director and head of acquisitions at TriGate Capital. “Accordingly, we’re seeing margins compress with growing inflation, payroll, maintenance, and insurance [costs], so there’s a likelihood that [net operating income] can actually decrease in the near term.”

A new world

A great sea change is now afoot in CRE, as investors across the various asset classes can no longer expect cheap financing to create high returns. For nearly two decades, falling interest rates have made real estate cash flows worth more, in turn lowering cap rates — a process known as cap rate compression.

Munk said that over the last 10 to 15 years, most returns in CRE — he estimated up to 80 percent of deals — were the result of cap rate compression. That way is now dead without much available debt and uncertain property values, he said.

“The world is now truly different, so we’ll see lower returns for the most part, because financing and cap rate compression won’t save anybody,” concluded Munk.

Stuart Boesky, CEO at Pembrook Capital Management, has nearly 40 years of experience in the industry. He said that when he started out investing in affordable multifamily properties, cap rates were 11 percent and many of those same properties were later sold by him and others at 5 percent cap rates. He laughed when noting that “it doesn’t take a genius” to buy and sell at those rates, and suggested that the industry is unlikely to experience a similar multi-decade run of generally falling interest rates, as occurred between 1982 and 2022, at least in the near term.

“In my mind, we’re at the end of an era of what I’d call ‘easy real estate profits,’ ” said Boesky. “Going forward, those people who make money in real estate are going to have to really create value.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com