Why Electricity Load Is Supplanting Location as the Driver in Warehouse Development

By Patrick Sisson October 26, 2023 6:00 am

reprints

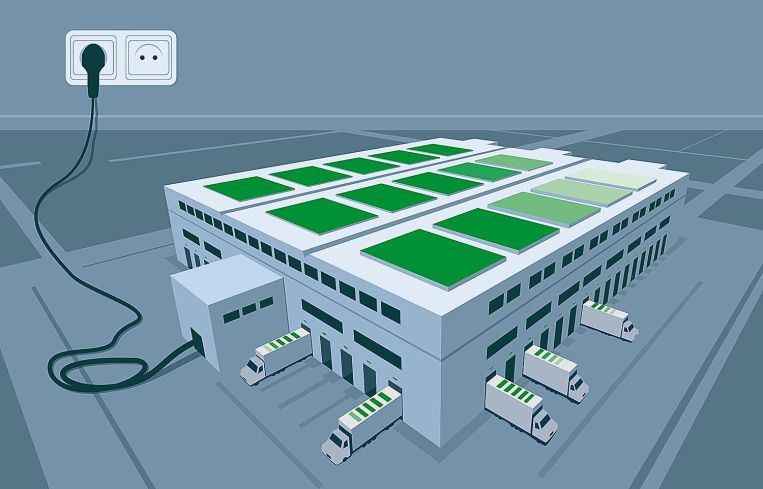

When the Bronx Logistics Center, a 1.3 million-square foot, multi-story warehouse, opens in the borough’s Hunts Point neighborhood at the end of the year, it’ll feature a number of cutting-edge features, including a large solar array and enough built-in capacity to offer full electric vehicle-ready parking for cars and trucks making last-mile deliveries.

The 14-acre site will also feature a more unique amenity: its own electrical substation, built into the project to help deal with the rapidly rising power needs of logistics and warehouse operations. It’s also a nod to the sustainability push in industrial real estate.

“This kind of focus on electrical power and sustainability used to be a box you’d check — 10 or 11 on your list of features to include,” said Ryan Nelson, managing principal with Turnbridge Equities, the project’s developer. “But now it’s a top priority — number 1 or 2.”

Even five years ago, siting and development of logistics and warehouse space used to revolve largely around location and transportation access, and finding the center of activity in terms of serving potential customers. Today, a more complex calculation has emerged around power supply, proximity to power lines, local regulations, and competition from power-hungry industrial users such as data centers and semiconductors.

New rules rolling out in California, including the state’s Advanced Clean Fleets and Advanced Clean Trucks mandates, mean electrified big rigs and a push for warehouses with more juice. It’s a long-term shift nationally around how warehouse and logistics projects are designed and built.

“Eighteen months ago, I would have said the biggest challenge that occupiers and developers were thinking about was labor and distribution labor,” said Mehtab Randhawa, global head of industrial research for JLL. “But, for the last 12 months, it’s been about power, power, power, and how do you get power to these facilities. We’re playing catch-up here, and we’re not ready for the demand coming from the development side.”

It’s not just due to the electrification of fleets and transportation, or the need for warehouse sites to charge a fleet of delivery vehicles all at once. Rising temperatures due to climate change have also meant more warehouses are installing air conditioning for the first time, adding to existing power demand for lighting, HVAC and ventilation. Warehousing and sorting centers continue to ramp up robotics and automation deployment, too, another draw on limited power supplies. Adoption of such technologies is now “table stakes,” according to industry trade group the Material Handling Institute, with tech investment predicted to jump 8 percent in 2023 alone.

The interiors of the latest generation of warehouses have significantly changed, said David Greek, managing partner at Greek Real Estate Partners, an industrial developer in New Jersey. Forklifts have given way to conveyor systems and robots, which steadily increase energy demands. Greek built a million-square-foot warehouse for Target in New Jersey that featured an extensive automation system covering half the facility. That necessitated the installation of 75 miles of conveyor belts and significant power upgrades.

But as far as the “elephant in the room” for warehouse electrification, it’s the looming large demand for fleet electrification, Greek said, which will require enormous new means of power generation and infrastructure investments, placing heavy burdens on utilities. At a Bisnow industry roundtable in California in May, industrial developers said the local utility, Pacific Gas and Electric, was the “primary cause” of construction delays.

Previously, developers requested, received and publicized massive electrical capacity for new projects, since it was a form of bragging rights and wasn’t typically monitored as closely by utilities. That’s changed as the sector, and other industrial users, have asked for more power.

“Utilities are giving a lot more scrutiny to the power requirements of warehouses,” Greek said. “They’ll give us a standard minimal service, what they deem an acceptable amount of electricity to run a standard spec warehouse. But developers are seeing much higher demand from our tenants. There’s a lagging issue where utilities are sizing power requirements based on an older model.”

Finally, many investors and name-brand companies have their own sustainability mandates to hit. That means projects like the Bronx Logistics Center stand out for ESG-focused tenants that are seeking last-mile delivery facilities and trying to figure out complex calculations around the transit costs of EVs versus traditional trucks and vans.

Turnbridge sees this kind of development as the future. The firm’s in-process projects at 807 Bank Street in East New York, Brooklyn, and a 1.3 million square-foot warehouse outside of Washington, D.C., will both have solar power and EV charging, and will pursue high ratings from the U.S. Green Building Council. The added costs of more sustainable development at the Bronx Logistics Center will be made back in no more than a year, Nelson estimated. International industrial giant Prologis has also invested heavily in renewables, sustainability and EV charging to appeal to changing energy needs from tenants.

Other developers are looking for sites near potential wind and solar sources, said J.C. Renshaw, a senior supply chain consultant with Savills. Having an alternative source of power has become much more important.

Tenant demand has become the driving force, even in regulation-heavy California, said Salim Youssefzadeh, CEO of WattEV, which is building out an all-electric shipping fleet and a network of 50-plus charging stations to offer big brands a turnkey, clean freight and logistics option. Youssefzadeh expects to field 1,000 such electric heavy trucks by 2026.

It’s the shippers that have pushed progressive parts of the industry to aggressively cater to clean trucking demand, he said. But many companies underestimate the time and cost of setting up their own EV fleet and charging network, providing an opening for firms like WattEV. Youssefzadeh said many sites WattEV initially pursued were tossed aside when they discovered it would take years to get proper power lines installed by local utilities — a sign of how power needs will upend traditional industrial siting decisions. In many urban areas, especially, continued growth, EV demand and the need for more last-mile delivery facilities weigh heavily on local power supplies.

“Time is money,” Youssefzadeh said. “We’re a startup and we need sites online now. We can’t afford to wait several years for a utility to act.”

Sourcing warehouse power is likely to become only more challenging as electrification and demand create more bottlenecks. JLL’s Randhawa said that since 2020, decision-making time to identify and OK industrial sites has tripled, suggesting just how complex and challenging this process has become. And the aging industrial stock will undoubtedly add to this pressure, Randhawa added. With the high cost of retrofits and surging demand, existing demand for EV-ready warehouses will only rise.