DeSantis-Disney Feud Clouds Florida’s Pro-Business Reputation

CRE leaders and GOP rivals begin to question archconservative's crusade against Disney, ESG and corporate power

By Chava Gourarie April 21, 2023 2:21 pm

reprints

Where to start.

Not even six months have passed since incumbent Republican Ron DeSantis wowed the nation on election night 2022, decisively routing his Democratic opponent in the race for Florida governor by nearly 20 percentage points.

In what used to be the swingiest of swing states.

In his victory speech, DeSantis excoriated the Blue States that were bleeding residents, a large majority of whom were headed to the Florida sunshine. “Those folks, Florida, for so many of them, has served as the promised land,” the reelected governor said triumphantly. They were coming to escape leftist authoritarianism and woke ideology. “We fight the woke in the legislature. We fight the woke in the schools. We fight the woke in the corporations. We will never surrender to the woke mob.”

It’s a fine line for the Florida governor to walk. On the one hand he’s attempting to curtail the power of private corporations in the name of fighting what he describes as woke ideology, while on the other, he’s the leader of the pro-business state of Florida and presumptively seeking the nomination of the political party that traditionally supports free enterprise and deregulation.

DeSantis is not exactly shy about his position vis-a-vis corporate power either. “Because major institutions in American life have become thoroughly politicized, protecting people from the imposition of leftist ideology requires more than just defeating leftist measures in the legislative arena,” he writes in his recent book, The Courage to Be Free, widely seen as his presidential soft launch.

But recently, the tightrope DeSantis is walking has begun to wobble.

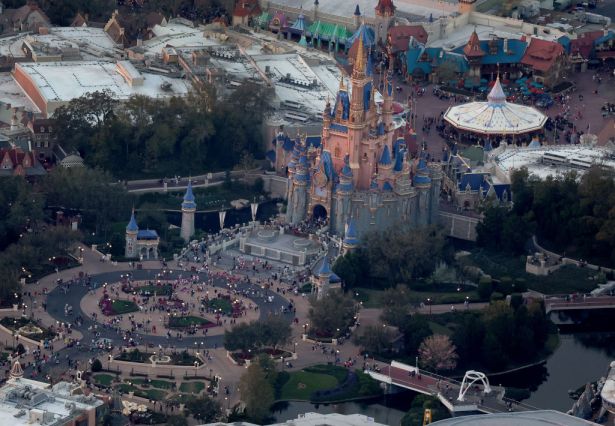

Nowhere is this more clear than in the tug-of-war the governor has gotten into with The Walt Disney Company which originated in March 2022, when the children’s entertainment giant publicly criticized the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law passed by the DeSantis administration. As the brawl has escalated in recent weeks, Disney CEO Bob Iger has called DeSantis “anti-business,” while DeSantis has threatened to build a competing theme park to counter the dominance of the House of Mouse.

Of course, his actions contra the entertainment giant are not a one-off. DeSantis is also one of the lead crusaders in the GOP fight against ESG, the progressive environmental, social and corporate governance framework widely adopted by financial and commercial real estate companies. Florida lawmakers passed a DeSantis-backed anti-ESG bill April 20 and it is now waiting for the governor’s signature.

It remains to be seen how his stance, which departs from the more standard conservative emphasis on small government, will affect DeSantis’s standing as governor and potential presidential candidate among the business community, particularly given the degree to which his state has benefited from being viewed as pro-business. It appears that in an effort to appeal to a Republican base, the governor is alienating some of the more conservative members of the conservative party.

“The Republican party has shifted from being a party that’s rooted in fiscal concerns to one that’s rooted in political concerns,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political scientist at the University of Houston. “That’s changing the way Republicans deal with financial matters with respect to companies.”

The origin of the Disney kerfuffle began last year, when under pressure from employees Disney criticized Florida’s “Parental Rights in Education Act,” which broadly restricts gender and sexual discussions in public schools. Critics say it’s a naked attempt at restricting any non-heteronormative representation in schools. After the bill passed, Disney officials went so far as to say that it was the goal of the company to have the law repealed.

DeSantis’ response was swift. His first move was to strip the children’s entertainment giant (and one of the state’s largest employers) of its special tax benefits during a special legislative session called just for that purpose, and he later installed a hand-picked board to control Disney’s home, Reedy Creek District — which is also, coincidentally, where DeSantis got married.

In the interim, Disney remained rather silent and even ousted Bob Chapek, who was CEO at the time of the “Don’t Say Gay” response, reinstating Iger, who hadn’t wanted to take a public stance against DeSantis, according to DeSantis’ telling in his book.

But, last month, it was revealed that the cat had been outsmarted by the Mouse. Before the new board was instated, Disney had bypassed its takeover by entering into development and restrictive covenant agreements with Walt Disney Parks and Resorts. In that agreement, Disney’s lawyers dredged up a quaint law regarding the lifespans of the descendants of a British monarch to essentially defang DeSantis’s hand-picked replacements before they even got started. Among other things, it would mean Disney could keep control of development in its 24,000-acre kingdom.

DeSantis, on book tour, lashed out that he would find a way to undo Disney’s underhanded move, which he followed up on last week, vowing to use the state legislature to nullify Disney’s nullification of the state’s nullification of its control over its tax district. DeSantis also floated possible uses for land controlled by Disney. “Maybe create a state park. Maybe try to do more amusement parks. Someone even said, like, maybe you need another state prison,” he mused April 17 in Tallahassee. “I mean, who knows? I mean, I just think that the possibilities are endless.”

The legislature followed through by passing an amendment allowing the new board, called the Central Florida Tourism Board, to invalidate Disney’s agreement, which it voted to do in a board meeting April 19 — all of which is expected to be challenged in court.

This fight with Disney may have escalated beyond DeSantis’s initial intent, but it’s part of a wider ideological view. At a closed-door conference in 2021 hosted by the nonpartisan nonprofit Teneo Network, DeSantis talked about the influence that tech companies wield and the need to use antitrust measures against them. “They’re just too big, they have too much power,” he said according to a video of the event obtained by ProPublica. “Those big companies are basically an arm of the ruling regime,” he added later.

A similar logic explains DeSantis’ crusade against ESG, an investing framework widely accepted within the corporate community and particularly popular within commercial real estate.

But to DeSantis, it’s “woke capitalism.” The ESG movement, and similar pushes within the corporate world to support a variety of social and civic positions, are an ideological incursion from the left, using corporations’ power to impose their will on the American people whether they like it or not, he argues. “I’m not content to just keep taxes low and stay out of anything else,” DeSantis said during a Fox News interview about his book. “My policies are helping to protect people from having the woke ideology shoved down their throats in institution after institution.”

The danger of woke corporations is enough to override their First Amendment right to espouse a political ideology without state intervention, per DeSantis.

But that approach gets messy quickly. That’s no clearer when it comes to ESG, since attempts to curtail it directly impede a business’ financial decision-making, the independence of which was once a sacred plank of GOP ideology.

In 2022, Florida pulled $2 billion from the state pension fund’s investments with BlackRock because of the investment house’s focus on ESG, which Florida CFO Jimmy Patronis framed at the time as a financial decision. “They have openly stated they’ve got other goals than producing returns,” he said.

DeSantis was a little clearer on the ideological component. “The ESG movement … represents an attempt to short-circuit the democratic debate by engineering hugely consequential policies via large corporations and asset managers,” he wrote in his book.

In addition, the Florida Senate approved a wider anti-ESG bill last week 28-12, along party lines, after the House passed a similar bill the previous month. The legislation prohibits local and municipal governments from investing in ESG-related products or participating in such funds by certifying their own bonds as ESG-compliant or as green bonds, among other restrictions.

Those restrictions can directly affect financial outcomes, as they have in other states that have passed anti-ESG legislation.

To asset managers, ESG is a form of financial risk, which makes it their fiduciary duty to consider. And, while an argument could be made that social elements are subject to societal whims that are not universal, environmental matters can and do directly affect a company’s financial outlook and must be considered to make the right financial decisions.

“A lot of these risks that are ESG risks used to just be called risks,” said Todd Khozein, the co-CEO of SecondMuse, which supports climate innovation. “ESG is a rubric for making an intelligent investment decision, considering financial risks; that’s all it is.”

Until recently, these unorthodox positions did not appear to hurt DeSantis’ popularity among Republican voters or businesspeople in Florida, as evidenced by his landslide reelection victory in November, and the number of companies and business-minded folks who have donated to his campaigns.

In March, for example, billionaire hedge fund founder Ken Griffin, who moved his company’s headquarters from Chicago to South Florida and donated a total of $10 million to DeSantis-related PACs, told Fox News that he’d love for DeSantis to run for president, the network reported.

But that was before the second blow-up with Disney, which has put the issue back in the spotlight, and before the anti-ESG movement began to lose steam as a top concern of some GOP members. Lawmakers in Indiana and Kansas have nixed or scaled back legislation restricting ESG in state investments when their own financial planners estimated it would cost them $7 billion and $3.6 billion, respectively, Bloomberg reported.

The crusade is not popular among Republican voters either, according to Penn State poll published in late 2022. In fact, more Republicans than Democrats opposed such moves, with 70 percent of Republican respondents opting against, versus 57 percent of Democrats, per the poll.

DeSantis’ likely presidential primary competition has also started to weigh on the governor. “DeSanctus is being absolutely destroyed by Disney,” 2024 presidential candidate Donald Trump wrote on his social media platform Truth Social on April 18. Trump also predicted that Disney’s next move would be to withdraw investment from Florida.

The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board and Republican Chris Christie, another presidential hopeful, piled on. “I don’t think Ron DeSantis is a conservative, based on his actions towards Disney,” Christie said in an interview April 18.

But DeSantis insists exactly the opposite. Bryan Griffin, a spokesperson for DeSantis, said DeSantis was acting in the best interests of the people of Florida. “Good and limited government (and, indeed, principled conservatism) reduces special privilege, encourages an even playing field for businesses, and upholds the will of the people,” Griffin wrote in a statement.