MGAC Founder Mark Anderson On Costs, Conversions and D.C.’s ‘Wave of Pain’

By Chava Gourarie March 13, 2023 8:00 am

reprints

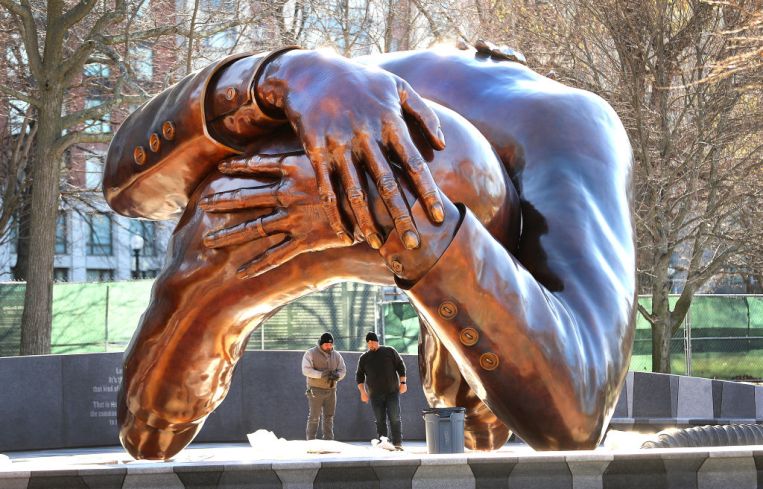

When “The Embrace” installation was unveiled in Boston Commons last December, it made quite a stir. The 20-foot-tall sculpture showing arms intertwined in an embrace honors Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, who met in Boston during their student days.

While most people rightfully focused on the artist, the art and the message, someone had to actually move and erect the 38,000-pound sculpture, a complex job that required cranes, construction crews and construction know-how. That’s where MGAC came in.

MGAC is a D.C.-based construction consulting firm that specializes in construction cost and risk management. It oversaw the process of assembling the massive bronze and stainless steel pieces.

Most of the time though, MGAC, founded by Alexandria, Va., native Mark Anderson, is involved in the more mundane world of massive construction projects: redeveloping the Newseum for Johns Hopkins University, as well as working on multiple campuses for the school; the reimaginings of 20 Mass and 1201 New York, both D.C. office buildings that needed new life; and a 1.4 million-square-foot ground-up corporate headquarters in the Midwest that, according to Anderson, MGAC is not allowed to talk about.

Recently, MGAC made its first acquisition of an outside firm, the more than 100-year-old U.K. firm RLF, in order to expand into new markets as well as increase its specialization. MGAC took the acquisition, and the lead-up to it, as an opportunity to redefine who they are as a firm, and where they want it to go next.

Commercial Observer spoke with Anderson from the MGAC office on 11th Street in Downtown D.C., about the acquisition, the hectic construction cost environment, and the future of D.C. office.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Commercial Observer: Tell me a little bit about yourself and about your company.

Mark Anderson: I grew up in Alexandria, and have been in construction since I got out of school. I helped pay my way through school working for Davis Construction, building high-rise concrete office buildings, largely in Downtown Washington. When I graduated school, I went to work for Davis and then kind of grew up through the construction industry here. I started MGAC in 1996, and grew it pretty much organically by trying to find people who are smarter and better at this than I am.

So the company grew organically for its first 25 or 26 years. Our first real acquisition was the U.K. acquisition of RLF in October of 2021. And that jumped our headcount and our revenue significantly.

As a firm that focuses on construction costs, the last couple of years must have been a bit of a roller coaster in terms of construction costs, to say the least. How has it been dealing with the rapidly changing prices together with supply chain disruptions, etc.?

Clearly our clients have struggled. The need doesn’t go away. So if you’re building student housing for a university, or if you’re building multifamily housing — and that’s been a booming business — or if you’re building cloud computing capability for data centers, or if you’re renovating a hotel — even with costs being higher, you have to do the project.

We did certainly have a phase, maybe nine or 12 months on the calendar, where construction costs went absolutely bonkers; lumber prices and commodity prices went crazy. I think that has calmed down now, and you’re looking at commodity prices going back to normal.

We were doing a very large project for an Ivy League university and we couldn’t get the technology components to do the project because of supply chain issues. We start the project, we get it going, and because they can’t get the technology out of a big giant technology company — Cisco, IBM, you name it — we had put the project on hold until they could procure it. Now, that supply chain is easing, and the project’s back online. So, yeah, we’ve been through it.

So your company is undergoing a rebrand. Is that mostly about folding RLF into MGAC, or are there other aspects that are also being rebranded?

Actually, as part of the RLF acquisition, we undertook a blind study nationally across the United States and across the United Kingdom to ask what mattered for clients in the procurement of project management and cost management services for construction projects.

It was a blind study, we paid a fortune for it, frankly. We really tried to discern what matters to clients, and then marry it, really, to who the essence of our brand is against what matters to clients. We’re a global boutique. We’re not the biggest cat on the block, intentionally. We know what we’re good at, and we’re really good at doing it. And we want to be very intentional about how we do it.

RLF is a really old company, dating to the 1800s. First of all, how did the acquisition come to be, and were there any cultural differences between a young-ish American company and a century-old British company?

How did it come about? We were quite intentional about wanting to do an acquisition in the United Kingdom. We engaged investment bankers in October of 2020 and we really went out and cast a net. We went through an identification process — really, the top end of the funnel of firms across the United Kingdom that met our criteria. We chucked out the ones that didn’t seem to make sense, for whatever reason; lack of alignment, lack of cultural alignment. And we winnowed it down to about 20 firms, after starting with about 100 firms.

We then approached the 20 through our investment bankers and began a series of conversations. Some are, like, “Heck, no, not interested,” right? Or, “Yeah, we’re interested, let’s talk more.” Through that process, we got down to about four. And, then, in the middle of COVID, we met with four firms over a series of about a week, and found some real alignment with RLF.

To what degree is the sustainable element playing a role when it comes to costs? How are people thinking about the short-term costs of sustainability, versus long-term benefits, with regulation coming down the pipe?

The U.K. is somewhat ahead of us on that. They’re looking at total carbon on a building. In other words, if you think about the life cycle of a building, the least carbon footprint for a building project is the building that never gets built — fairly obvious. Adaptive reuse and reuse of existing structures is certainly on the rise given the carbon involved in building a building. Concrete is a very carbon-intensive material; steel production is very carbon-intensive.

We have two major mass timber projects now that are going up. One is a corporate headquarters. The other is a very large academic project. Both are looking at their carbon footprint.

The U.K. aims to be carbon neutral [by 2050] so we have to have a plan to get to carbon neutrality for our business in the U.K., which is something we’re certainly not seeing in the United States. But, in the United States, you know, 10 or 15 years ago, it was LEED, everybody had to be LEED this and LEED that. And, finally, LEED sort of became, well, everybody’s LEED. What’s next? We got to WELL buildings and everybody had to have a WELL building. And then people were on to Energy Star buildings because they’re the most energy efficient. It’s sort of an iterative process.

As things have gotten more and more sustainable, and there’s more and more attention being paid to carbon footprint, the sourcing of materials and the locality of materials … I think buying the last tree out of the rain forest is getting harder and harder. Everything’s just more sustainable.

In terms of adaptive reuse, is there a point at which the cost of the adaptive reuse and bringing it up to modern standards can’t be recouped, especially with the office market being what it is right now?

I think there’s a question about what the economics of office buildings in Washington, D.C., are, period.

That’s a nice way of saying it.

We have a client now who’s building over a million square feet of workplace for their workforce, so they obviously believe that people are going to come sit at their desks in their new multibillion-dollar building. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be doing it. We’re not doing the Amazon campus across the river, but obviously Amazon thinks that somebody’s gonna be sitting in National Landing at their desk doing something. So big business actually believes people are gonna be back at their desks in some way, shape or form, or they wouldn’t be dropping billions of dollars on doing it.

You look at what were trophy buildings in Washington, D.C., when they were built, and you could rattle them off, buildings that were built maybe from 1990 to maybe 2010, and, really, their prime leases expire and their primary tenants move out after 10- or 15-year leases. Suddenly, it’s a big vacant, gaping hole; there’s still underlying debt. I think all of those economics are very much up in the air.

Much of Downtown Washington was driven by General Services Administration leasing and major law firms. Now that consumption is basically dried up, or at least a fraction of what it used to be, I think office assets, especially aging movie-star assets, if you know what I’m saying, are deeply troubled assets because people aren’t backfilling.

D.C. is a challenge because it has such concentration of a particular type of office asset and a particular type of tenant.

The mayor is talking about it, begging the federal government to come back.

When we first got back in May 2020 — because construction never really stopped — it was really hard to get a sandwich, everything was closed. Now, it’s not all back, but it’s 60 or 70 percent back. But the 70 percent of businesses that are back are subsisting on 70 percent of their pre-COVID business. My dry cleaner says, you know, his business is 60 percent of what it used to be because people aren’t dressing up as much.

Are you doing any office-to-resi conversions?

No. We’ve looked at them, and I’ve actually talked to a couple of developers about it. And it’s interesting because every building on this block is conceivably for sale, and we’re on top of a Metro stop adjacent to City Center. If I had a blank piece of paper, and if values were different, I think this would make a great residential block with a grocery store and that sort of thing.

The problem is the values are still too great; they haven’t fallen far enough in the office building market really to justify the expense of conversion. I’m told uniformly by developers that to convert an office building to residential, the underlying asset needs to be purchased for about $200 a square foot. Right now, prices are closer to the $400 to $600 per square foot range. So I think there’s a wave of pain coming to a lot of lenders and a lot of developers in Washington, D.C.

We’ve seen it before. It happens about every 10 years. Buildings go back to lenders, lenders don’t want to own real estate, so they sell them back at a fraction of what they have in it to mitigate their loss. And, we’ll see, I think we’re seeing a redevelopment of Washington.

But you know, that’s the real estate cycle.

Chava Gourarie can be reached at cgourarie@commercialobserver.com.