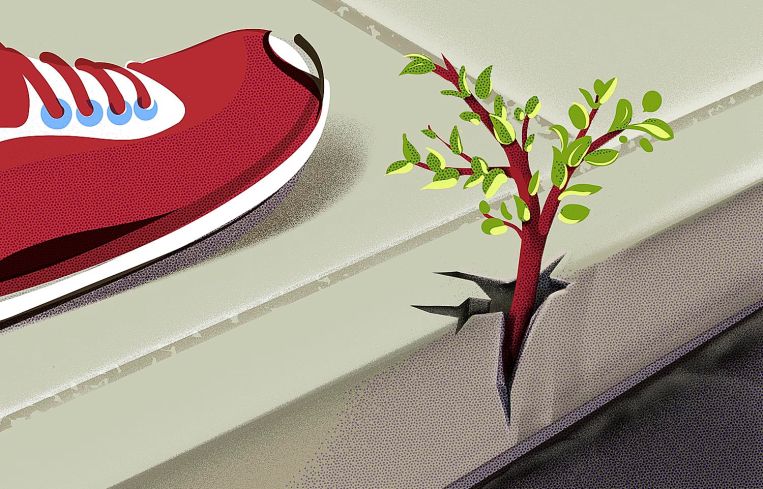

Brooklyn’s Office Market Post-COVID Sows Green Shoots

Any recovery, though, confronts the same challenges as before the pandemic: lots of available space and uneven demand

By David M. Levitt January 31, 2023 9:00 am

reprints

Optimism springs eternal in the Borough of Churches.

Just southeast of arguably the world’s grandest and most expensive office district — Midtown Manhattan — hovers the long-standing hope that something new and more progressive would spring up in its shadow.

Blondel Pinnock is a believer. As president and chief executive officer of the nonprofit Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, she has plans for 840,000 square feet of potential mixed-use property in just about the center of the borough riding on it. The Restoration Plaza project, which might take 12 years to unfold, could cost as much as $700 million. Right now it has a $50 million city commitment.

Pinnock’s corporation is leading the 21st century version of Restoration Plaza, which would more than double the size of the complex that has been central to Bedford-Stuyvesant for more than half a century, going back to the administrations of Mayor John Lindsay and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. The complex — which combines offices, retail (including an Applebee’s restaurant and a supermarket) and a cultural component that teaches young performers — is designed to give residents marketable skills and to help companies find competent workers.

Pinnock has heard about the difficulty other projects around the borough have had getting off the ground. But she remains resolute.

“People do have trepidation about that, but, as a woman who’s worked in banking for the past 20 years, I know that there are many economic cycles, and this is just one,” Pinnock told Commercial Observer in late January. “By the time we are ready to put bricks down for this building, there will be several economic cycles. I know that some say this is crazy, but I can guarantee you there will be several economic cycles between today and when we get this project done.”

Brooklyn has been New York’s budding, new 21st century office market for more than a decade now. In the late 2010s, investors were falling over themselves to bankroll projects to convert old industrial space to office, or build from the ground up brand new, or create sparkling new offices out of Downtown properties that had been owned by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were relocating to upstate New York.

The promise was always the same: Brooklyn had become a prized place for people to live, with neighborhoods like Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Bushwick and Gowanus flourishing like never before. Residential towers shot up downtown, filled with the nouveau riche. And people would want to work close to where they lived, and not spend hours in traffic or on a train.

Then life happened. For two years, a pandemic froze just about everyone in place. Manhattan struggled, its suddenly vacant space offering deals to tenants normally priced out and thereby creating competition for Brooklyn where there hadn’t been any. And now there’s worry that a recession could be on the horizon.

“With a 21.1 percent availability rate and additional inventory scheduled for delivery over the next several quarters, the Brooklyn office market is challenged with an abundance of supply in nearly every submarket while the demand continues to be driven by a few select industries: education, government, nonprofit and health care,” said Franklin Wallach, executive managing director of research and business development at Colliers, in an email. “The creative industries have continued to play a role in Brooklyn’s demand. But this has mostly been Brooklyn-based with limited cases of Manhattan tenants relocating or expanding into Brooklyn.”

That’s been the nagging reality for the Brooklyn office market: Plenty of new supply and really only niche demand even before the pandemic deadened demand that much further. Meanwhile, the supply keeps coming. According to Wallach, developers are slated to deliver about 3.66 million square feet of office space in Brooklyn between now and 2026. Nearly all of that space is unspoken for. Between 2018 and 2022, about 5.85 million square feet was added and about 55 percent of that remains available, Wallach said.

“Throughout the pandemic, Brooklyn hasn’t been badly affected on absorption and additions to supply, partly because there was already quite a bit of supply on the market,” said CBRE’s Mike Slattery, an associate field research director. “So there wasn’t a lot of shedding from those companies. The biggest challenge was demand.”

Overall, nearly 1 million square feet of office space was leased in 2022, according to a CBRE report, about 2 percent higher than the previous year’s year-end total. Asking rents were up 5 percent from the prior year, to $48.91 a square foot.

The big concern, said Slattery, is that a coming recession could hit the entire commercial real estate market hard in 2023, including Brooklyn. Goldman Sachs estimates that the chances of a “meaningful downturn” this year are about 65 percent.

“We’re over the pandemic hurdle, but some of the challenges still remain,” Slattery said. “Work from home or remote work still has an impact for the entire office market across the country. And I think we’re entering an environment where we’re expecting a recession. Economic headwinds make it really hard to say” whether there will be a huge step toward further recovery. For several high-profile projects near the bank of the East River — with enviable views of Manhattan and its skyscrapers and the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge and the Statue of Liberty across the harbor — that means 2023 could be another year of scraping by, putting together leases one by one, without landing the big fish headquarters that would create worldwide buzz.

There are properties competing to land that prize. The 500,000-square-foot, 35-story 1 Willoughby Square downtown, completed last year, is Brooklyn’s tallest office building. It just crossed 50 percent leased, according to CBRE, whose Paul Amrich and Neil King are in charge of leasing it. “We see a trend that right now that feels really good,” Amrich, like King a vice chairman at the brokerage, said. “We’re always analyzing the market through what we call a pipeline — which is interest level, paper, LOIs (letters of intent) — and we’re seeing a pretty good pipeline at the moment.”

Or take the Refinery, a landmark 19th century factory building at the former Domino Sugar plant in Williamsburg, where mostly residential towers have been built. According to CBRE, which oversees the leasing at the Refinery, there have been no deals since the firm started advertising the space in earnest last summer. That was mostly after Two Trees, the company that developed Brooklyn’s Dumbo district, put $250 million into upgrading the building — essentially putting a brand-new building inside the shell of an old one — and landing two gigantic loans from lenders who wanted to be associated with the project: $350 million from JPMorgan Chase for housing that’s part of the development and another $80 million from M&T Bank.

In January, the co-working giant WeWork announced it was cutting 300 of its employees and shrinking its Dock 72 hub, a newer building at the Brooklyn Navy Yard that WeWork is supposed to anchor. It was one of several technology giants that have in recent weeks announced large layoffs as well as plans to ditch surplus office space, including by subleasing it.

Asked to comment, Rudin Management, which co-developed the building along with Boston Properties, said in a statement: “Dock 72 continues to attract top-tier creative companies seeking office environments that reflect the future of the workplace. We completed three headquarters leases in the second half of 2022, all to growing companies relocating from other Brooklyn locations. They join WeWork and Food52, which is relocating from Manhattan.”

The market does have surprises in it, too. Office leasing activity spiked 91 percent quarterly in the last three months of 2022, according to CBRE. In fact, activity ran 30 percent above the five-year average for Brooklyn. And then there are pockets of vibrancy, some of them quite unexpected. Several startup cryptocurrency companies made a colony for themselves in Bushwick, a neighborhood of homes and obsolete industrial properties that few ever considered for offices. Though cryptocurrency had a highly publicized setback with the December arrest of Sam Bankman-Fried on money laundering and wire fraud charges tied to his FTX crypto exchange, it still has a core of believers working hard to keep the proverbial lights on.

And Industry City, an early 20th century industrial park between the Gowanus Expressway and the water, has garnered enough leases with startup “maker” companies to give Pinnock of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation hope regarding Restoration Plaza’s prospects:

“Something like that would be amazing.”

This article originally appeared as part of the Tenant Talk newsletter. Please consider subscribing to it and other Commercial Observer newsletters here.