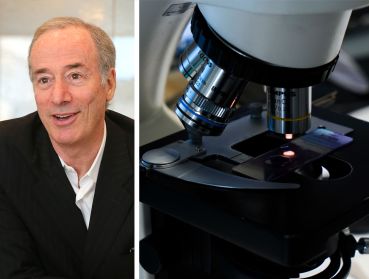

KBA’s Jason Aster, Ex-Corenet Chair, On What Tenants Really Want in Their Offices

‘Landlords are trying to one-up what people are getting in the residential setting’

By David M. Levitt December 13, 2022 9:00 am

reprints

Jason Aster is what we in journalism call a twofer.

As managing director of KBA Lease Services, a consultancy that helps companies optimize the costs of their leased portfolios, Aster provides guidance to corporations looking to enforce the economic intent of their leases by recovering rent overcharges and reducing occupancy costs.

As chairman emeritus of the New York chapter of Corenet Global, the largest networking and educational organization of corporate real estate executives, he has an inside view of what companies want from their offices, which these days generally means a smaller, more purpose-driven space.

For landlords, that’s troublesome. It means that in this post-COVID world, most businesses are not going back to the days when a large opulent space shouted to the world “We are here,” and workers were obligated to show up in person — so deal with it.

That means skyscrapers that once seemed too small to contain the ambitions of some of the world’s most ambitious companies are now looking too big, and are likely to remain that way for years. Either you optimize the space, maximize its attractiveness for a workforce that has a choice whether to come in or not; or you consider converting a building, or have a buyer convert a building, into apartments for the seemingly insatiable demand for housing.

Aster jumped on a call in early December to talk about this moment in time and the unprecedented sensitivity of talks between landlord and tenant.

His remarks have been edited for clarity and length.

Commercial Observer: How did you become president of Corenet’s New York chapter?

Jason Aster: Probably by mistake. I had been a member of Corenet since 2010 or 2011. I had been a young leader, and been very active with content creation and networking. And I happened to be a lawyer, and I was their counsel for a good number of years. And after a few years, it was time for a refresh of leadership. They took me because I was younger, but I had a lot of deep experience in the organization. We went through a kind of soup-to-nuts restructure of the divisions of the board — who’s doing what and why they are doing it.

I’ve been emeritus since right before the pandemic, 2019.

Talk to me a little bit about Corenet, and why it is important relative to the overall real estate industry.

It’s still the largest networking and educational nonprofit in the world with respect to the ecosystem that is corporate real estate — every vertical that could touch commercial real estate. You have your major brokerage firms, your architects, people who do all sorts of professional service work for tenants, legal, audits, etc., all serving the big tenants, all across the world, who are leasing space. The main focal point has always been the perspective of the occupier.

So you have some strong opinions about amenities, and how important they have become relative to the space decisions companies have to make, coming out of the pandemic. There has been a focus on luring tenants back because you can’t really count on them. So give me your perspective on what amenities are vital and what are window dressing.

Pre-pandemic, there was still a race for amenitizing space. Using New York as an example, a lot of the brand-new space was under construction and finished before the pandemic, right? Hudson Yards, Manhattan West, One Vanderbilt — these all came with the who’s who of amenities, like a high-end hotel or hospitality.

It went from “Can I duplicate your home experience?” to “Can I one-up that with a more hospitality-focused product?” And, in a really interesting parallel, if you look at who buys homes in really expensive places like Manhattan or San Francisco, and what they want in their apartment, if you are buying a house for $3 million or more, you’re not asking for things like a pool or a doorman — you expect those things. What they want are the outdoor spaces that you can’t get at your house, the basketball court.

Landlords are trying to one-up what people are getting in the residential setting. So you’re seeing things like training facilities, really good conference room technology, anything hospitality-oriented; your big outdoor event spaces.

You can keep the office, change the context of why you would use an office, reduce your footprint over time and actually get higher-quality, more usable space for less money. It might be more per square foot; you’re spending a lot per square foot to actually change the fit-out of your space. But you’re taking less space because you don’t need as much dedicated space for corner offices and so forth. So there’s some pretty good cost savings that can come out of this.

Are there things that you see that are a waste of money, or has pretty much all that you have seen been positive?

I’m not sure there’s a standard answer for that. It takes every type of employee, and each employee is different. Say the Empire State Building wants to put in a basketball court. That would not be useful for my company.

Is that useful? I don’t know. It’s expensive. The big question is who ends up paying for these things?

The things that tend to be useful are things that you can’t really replicate at home and that also create collaboration. The things that are less useful, or at least less surprising, could be a cafeteria, which has been around forever. Companies can do very specific, very high-end catering. I’m not sure you need a cafeteria for that.

Your cafeteria may be a wonderful experience. That might be good. But I think everything has to be thought through.

You mentioned cost. Is cost close to becoming a major clash point between landlords and tenants? For several years now there’s been a trend toward landlords picking up more and more of the fit-out costs. But I’m wondering if there’s a concern now over who’s going to pay for that basketball court, who’s going to pay for that cafeteria, who’s going to pay for furnishing that outdoor space?

Pre-pandemic we were seeing tenant improvement allowances rising between 10 and 50 percent per year. The numbers were going pretty high. Landlords were willing to invest quite a bit of money in a tenant taking space and doing what they want to that space.

What we’re talking about now is a landlord shifting that attention to their own space. Tenant floors have become truly vacant and they can’t re-lease it, the tenant is no longer there, there’s no lease on the space. The landlord has to figure out what to do with this space. So cost is a big deal because they have to put something else in this vacant space that is either accessible exclusively to their tenants in the building, or create a business that is accessible to the neighborhood, more like a retail front.

The landlords are gambling: “What am I going to invest in these floors that may have previously been high-rent tenants that is going to create even higher-rent tenants in the reduced amount of rentable space I have?” If I have 10 floors and one of them becomes vacant, I can now rent only nine floors, and I have to figure out how to get the rental value out of nine floors to eclipse what I am losing. And I have to invest in that.

So cost becomes a huge, huge deal. And you’re not talking a few thousand dollars. You’re talking hundreds of millions. So these are big gambles they have to make.

There are several prongs to cost. Who pays to make the amenity? Take the example of a building that already exists, not that’s being built from the ground up; and they’re taking newly vacant space and turning it into a basketball court or a cafeteria or whatever it’s going to be. Who’s going to pay to do the conversion, and who’s going to pay to operate it? And what type of operating costs are we talking about?

Are we talking pay-to-play like a parking lot? Are we talking about a free-for-all, tenants can come into the space, but the landlord has to create a management agreement with a third party to upkeep the space and have hospitality elements there? It gets very murky.

We’ve seen some exotic amenities like bees on the roof and golf simulators. I can understand the appeal of an outdoor terrace. And I can understand the appeal of a cafeteria, or a catered lunch. But some things are being tried that seem to me a little edgy, right?

To me, it boils down to whether you find it useful or not. That’s going to be a negotiating point when you’re striking a new deal. So coming into a building that has bees on the roof or they are very ESG-minded — they have a really cool filtration system and a green roof that’s supposed to get you carbon neutrality — I might say that’s very important to me, or as a company that’s very important to my employees, and I’m willing to pay a premium in my rent.

What message are Corenet members getting regarding downsizing? Are they hearing from their corporate parents that they want to downsize? We just saw the other day that AECOM, the engineering firm, is taking less than half the space it previously rented at 100 Park.

We’re hearing a lot. I can speak more about it as a representative of KBA. We represent hundreds of global tenants. We talk to them every day, we know what they’re doing. They have to tell us because we’re reviewing their offices. It’s the same thing that we’re seeing at the CFO or finance or head of real estate level.

Reducing a portfolio is a thing, whether it’s Class A space that is underutilized, or in mid-market, where you had an office for 20, 30, 40, 50 people, or reducing large footprints, single buildings in central business districts. It’s happening relatively across the board.

We don’t have too many clients that are calling us and saying, “We’re taking more space right now.” There are some. But there is both a realization that hybrid works and we don’t need as much space. I’m not hearing a realization that we don’t need space, period. I’m certainly hearing that we don’t need as much space.

That was also true pre-pandemic. The United States was way underutilized pre-pandemic compared to the rest of the world. We were kind of due to face a reckoning anyway.

New York makes up 10 percent of office buildings in the United States. So if you have an effort to reduce office space, that’s going to hit New York differently than the rest of the world. And the ripple effects of that I think we’ve seen to some degree in 2008 and 2009. But this is different.

There are firemen and teacher pension funds and 401ks and there are all these investment instruments that are tied up in buildings in Boston, in Atlanta, in New York, for people across the world, not just in New York. So I think there needs to be a broader conversation.