Midtown South: Where Does It Begin and End Now?

The answer is important to tenants and landlords

By David M. Levitt October 10, 2022 9:11 am

reprints

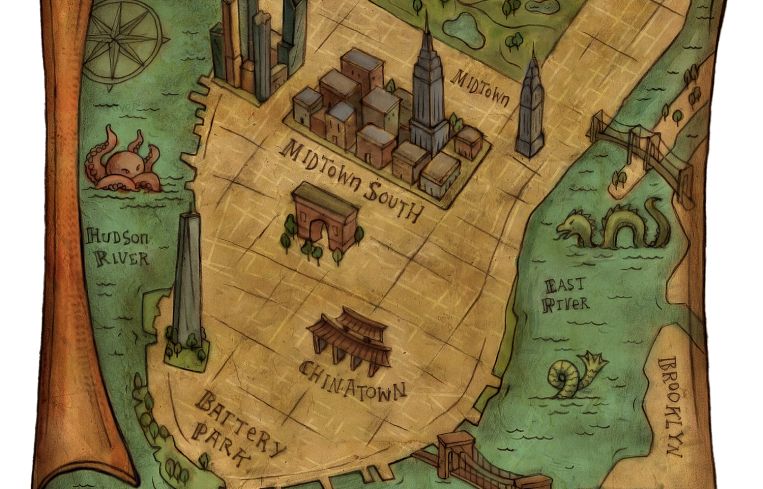

Where does Midtown end and Midtown South begin? The answer used to be so clear and now it’s not.

For some it’s just south of 40th Street, thus taking in the towers just below “The Deuce,” the wide boulevard of dreams known as 42nd Street. For others, it’s around 30th Street, so it includes the Empire State Building. With the rise in the last 20 years of the tech industry in New York, the border between Midtown and Midtown South has become a crucial demarcation for asking rents for offices, locations for retail and restaurants that service those offices, and the simple bragging rights of companies hanging out their shingles.

Somewhere between 40th and 30th streets is where the city’s traditional banking and finance industries give way to tech and other creative types. Madison Square Park on 23rd Street, and its environs, define it. The area is a regular hangout now for New York’s 20- and 30-somethings who have grown up with computers on their laps and in their pockets.

Hudson Yards, the long-planned western extension of Manhattan’s Midtown business district, further complicated things as it became a reality over the last few years. For a certain segment of commercial real estate cognoscenti, there’s a question of where the largest private real estate development in modern U.S. history belongs. With its largely financial brethren as part of Midtown? Or because most of Hudson Yards is south of 34th Street, does geography rule?

Just about all the major real estate service companies decided a long while ago Hudson Yards is an extension of Midtown and have put its statistics into their overall numbers for that section of town. Many came up with a submarket they called Times Square South, made up of the business district south of The Deuce, and made it part of Midtown.

Except one firm does it a different way.

Colliers, one of several commercial property brokerages that serves the borough, decided to lump Hudson Yards in with the low-rise neighborhoods, like Chelsea, Flatiron and SoHo — collectively known as Midtown South. Its statistical gurus see it mainly as a geography thing.

“We, meaning Colliers Research, always drew the dividing line between Midtown and Midtown South at essentially the southern end of Bryant Park (40th Street),” said Franklin Wallach, executive managing director for research and development in Colliers’ New York office. “You can really feel the change from Midtown’s glass and steel to the brick and mortar that defines Midtown South.”

Colliers defines the submarket as including not only Hudson Yards, but also the similarly shiny and newish Manhattan West, Brookfield Property Partners’ 8-acre development west of Madison Square Garden, and Vornado Realty Trust’s redeveloped Farley Building, soon-to-be home of Facebook and Instagram parent Meta. Colliers also includes in Midtown South the Spiral tower to the north of Hudson Yards being built by Tishman Speyer, and 3 Hudson Boulevard, a skyscraper across from the Javits Convention Center that’s a joint project of Boston Properties and the Moinian Group. It is called the Hudson Yards-Manhattan West submarket.

Pre-Hudson Yards there were buildings in that area like 5 Manhattan West — the former 450 West 33rd Street, the pyramid-like tower west of the Garden — and 475 10th Avenue that were attractive to tech enterprises and were always classified as Midtown South, Wallach said.

That means the largest lease transaction of August — the accounting giant KPMG’s 456,000-square-foot lease at Brookfield’s 2 Manhattan West, a tower nearing completion — took place in Midtown South, at least according to Colliers, impacting the entire Midtown South market’s availability rate and leasing activity. It means that one transaction accounted for almost a third of its 1.56 million square feet of activity that month. That made Midtown South the most active Manhattan market of the three that brokerages track — Midtown, Midtown South and Downtown — beating out Midtown’s 1.34 million square feet.

Rivals such as CBRE, Cushman & Wakefield and Savills see Hudson Yards as an extension of Midtown, noting its appeal to Midtown’s traditional finance tenants. They also point out its architectural similarities, such as its penchant for high-rise glass and steel towers. JLL has made Hudson Yards its own 11.6 million-square-foot submarket as a part of Midtown. CBRE put the Yards together with the Penn District, which are the office buildings close to and around Madison Square Garden and Penn Station.

“When you look at a map of where Hudson Yards resides, Hudson Yards for us really fits into Midtown,” said Marisha Clinton, senior director for Northeast regional research for Savills.

Savills places the southern boundary of Midtown at 30th Street, capturing the whole of the Hudson Yards development as well as the Empire State Building. “The way we have it, it borders West 42nd Street on the north, Ninth Avenue on the east, West 30th Street on the south, and on the west it goes beyond 12th Avenue, pretty much to the Hudson River.”

Architectural style is not sacrosanct, nor is the attraction of finance companies to Midtown. Also, technology and creative companies — think advertising firms and those that make films, video and other media — cluster in Midtown South, though clusters of both industries exist in both markets, said Wallach. There are computer-based companies in Midtown, like Microsoft and Salesforce, and finance companies, most notably the investment bank Credit Suisse, recently joined by the mutual fund giant Franklin Templeton, in Midtown South, he noted.

“There’s a mix of tenants that have migrated over to Hudson Yards/Manhattan West,” Wallach said. “Don’t forget Facebook, Coach, L’Oreal, and, yes, some financial professional service industries as well, so it’s a fair industry mix.”

Traditionally the commercial real estate industry has seen Manhattan, by far the largest and priciest business district in the United States, as divided into those three major markets: Midtown, Midtown South and Downtown. They, in turn, encompass an abundance of more bite-size submarkets whose statistics influence thousands of deals and negotiation hours a year. For example, Savills divides Manhattan below 59th Street into 19 submarkets, such as the Plaza District North and South (named for the properties in the immediate vicinity of the Plaza Hotel), for the longest time the city’s priciest office market.

According to Savills second-quarter report, Hudson Yards had the city’s lowest availability rate, 5.4 percent, and the second-highest asking rents at $122.84 a square foot on average, trailing only Plaza North at $129.59. Manhattan overall had rents that averaged $82.86. Its overall availability rate was 11.8 percent. Midtown South sported an 18 percent availability rate and an average rent of $83.49 a square foot, actually higher than Midtown proper’s $82.84. (The recent parity in pricing has also helped blur the lines between the two markets; for decades Midtown South was the much cheaper option.)

Related said it had no comment on where its Hudson Yards is placed. Spokeswoman Kathleen Corless noted that all completed Hudson Yards office towers are 100 percent filled — that’s 3.7 million square feet — and 50 Hudson Yards, a 2.9 million-square-foot tower that remains under construction, is 84 percent leased.

At this time there is no timetable for building out the second phase of the project, the so-called Western Yards, which is supposed to contain a mix of residential, office, resort, entertainment and gaming uses, plus open space. Related recently applied with Wynn Resorts for a casino license on the western portion of the site. Most of the development is built over the MTA rail yards that serve the largely Long Island Railroad trains that run in and out of nearby Penn Station.

The difference in classifying Hudson Yards highlights the sometimes subtle differences between different brokerage houses and how they count up the market. For example, Colliers defines Manhattan’s total office inventory as 540 million square feet, counting every building of 25,000 square feet or more, Wallach said. Cushman puts the borough’s office market at 412 million square feet.

From the standpoint of the tenant-customer, it doesn’t really matter what submarket is placed where. All the brokerages, as part of their client services, will make customized reports, digging into markets the client has specified, identifying what their competitors and peers are paying, as well as other information the client wants to inform its decision. Brokers report that clients have become less and less interested in being in specific neighborhoods and are more willing to look all over the city, including the outer boroughs.

“Some markets do matter,” said Michael Slattery, a CBRE associate field research director. “But it’s not a brick wall.”