More CRE Firms Are Putting a Price on Their Climate Exposure

Execs are using climate intel to inform investment decisions

By Chava Gourarie July 27, 2022 3:00 pm

reprints

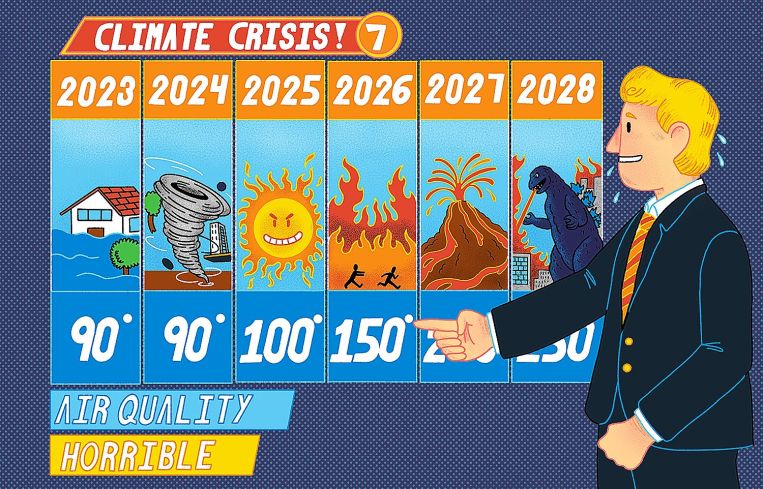

Throw a dart at a globe, and you will hit a recent, or current, climate-related disaster. In July, 100 million Americans were under an extreme heat warning, Western Europe was on fire, London broke 104 degrees Fahrenheit, and Delhi, which broke 120 degrees for the first time in May, was again experiencing a deadly heat wave.

Each one of these events is an outlier, but taken together, it’s a pattern that suggests that it’s prudent, if not crucial, for commercial real estate investors, owners and lenders to evaluate their exposure to a changing climate.

Some lenders and real estate investors have already begun incorporating climate intelligence into their decision-making, while a crop of startups and consultancies are building real estate-specific platforms to provide actionable climate intelligence to guide them.

“It’s in the name,” said Karan Chopra, the COO of Cervest, one such climate analytics startup. “Given that it’s real estate and real assets that they care about, [real estate] is actually one of the sectors that is most interested in thinking about how to use climate intelligence. Because, at the end of the day, that affects both growth decisions that they’re making as well as asset protection and value protection decisions on their portfolios.”

Until recently, sustainability in a corporate context referred almost exclusively to a company’s carbon footprint, which in real estate meant a move towards cleaner energy, electrified buildings, and more sustainable building materials.

Now, as the effects of climate change become more pronounced, corporations have begun to focus not only on their carbon contribution, but on their climate risk as well. To understand their exposure, big banks are snapping up climate data startups, rating agencies are beginning to integrate climate risk into some rating assessments, and early adopters in real estate are beginning to assess what their exposure to further climate change might mean for their portfolios.

“There’s an increased recognition that resilience is a part of ESG,” said Mark Nelson, head of advanced technology and research at Arup, an engineering and design firm which has its own climate intelligence platform. “People are paying attention to the value and cost of retrofit and repairs.”

In essence, companies like Arup are trying to put a price on the impacts of climate change.

These are very early days, however, so there isn’t a standardized way to measure the wide range of potential risks — from extreme heat and failing infrastructure to water pollution and population loss — facing all aspects of the built environment.

That’s changing, though.

“The most sophisticated lenders, as well as the [government-sponsored enterprises] are now evaluating their entire mortgage portfolio for all the risks that they used to evaluate on an ongoing basis from a risk management perspective, plus climate risk that matches the duration of the loan,” said Rich Sorkin, CEO of climate intelligence platform Jupiter.

“If you hold a mortgage, or a commercial loan for real estate, even if you assume that it’s going to get refinanced, you have to evaluate what the economic environment is going to be at the time it’s refinanced,” Sorkin added. “Now people don’t price [climate risk] in, but they will in 10 years.”

The risks that companies may incorporate into their portfolio assessment include four categories. The first is physical damage, as in the damage an asset might suffer if it’s clobbered by floods, wildfires, hurricanes or other extreme weather events. As a corollary, the infrastructure fallout from one of these events could cause business interruption, or “downtime,” even if your building is untouched — say, if the roads are impassable, the power is out, or you’re under an evacuation order.

The third and fourth categories are migration risk and transitional risk from policy, regulations and economic shifts, like New York’s Local Law 97, the upcoming disclosure rules from the Securities and Exchange Committee, and land use changes.

In fact, transitional risk might be the most acute. “Insurance and regulation are the most immediate risks that are driving the acceleration of climate assessments,” said Billy Grayson, an executive vice president and sustainability expert at the Urban Land Institute.

All categories of risk apply not only to outlier events, but to persistent change. Once the sea rises, it doesn’t drain away. Once the planet’s average temperature warms by 1.5 degrees Celsius, it doesn’t go down. Cities will therefore have to adapt to persistently higher temperatures, more average rainfall per year, longer hurricane seasons and other changes.

Companies can approach an assessment of risks in a number of ways. Most begin with a portfolio-wide screening to identify their most vulnerable, or highest-priority, assets.

Arup’s portfolio assessment grades each building on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being the highest level of risk. The grading accounts for both climate exposure as well as property value, along with other factors. “Class 1 is high-level triage,” said Nelson. “If we’re looking at a whole portfolio, we’ll start with Class 1.”

After a screening, the next step is to drill down to specific assets. In this scenario, Nelson said, the purpose is often to decide which adaptive measure to take. “When the storm comes, or the flood comes, what are the direct impacts? Electrical? Hurricane damage to the roof? Flooding in the underground garage? It helps them decide where to spend capex.”

A third purpose for climate assessment is not for existing buildings, but for guidance on future acquisitions, investments and site selections. It could also inform decisions regarding what to build, and how, though the latter is generally the purview of engineers..

Applying the intel to business decisions is dependent on the client’s investment strategy, appetite for risk, geographic concentrations and outlooks on the future.

Presidio Bay’s K. Cyrus Sanandaji, takes a broad-brush approach, choosing to sidestep more obviously vulnerable markets altogether. “I’m not particularly interested in developing Florida,” Sanandaji said. “Because, if we’re talking about 6 to 9 feet of sea level rise, almost that whole state is gone.”

That’s not because he’s ignoring the issue. On the contrary. Sanandaji is active in the San Francisco Bay Area, and is integrating climate models into development plans, including Pier 70 in San Francisco. He’s chosen to make the projects resilient to up to 9 feet of sea level rise, the upper limit of most emissions scenarios. “There’s no way that we can predict a rate of change accurately, to be able to make long-term institutional bets,” Sanandaji said. “So what we’re making are just directional bets, as it relates to mitigation.”

Asi Cymbal takes a different approach. A resident of Surfside, Fla., and principal of Cymbal Development, he isn’t abandonig Florida. “We all know the wind speeds are going to increase in velocity and we’ve prepared for that,” Cymbal said. “Before we finalize our structural plans, our design needs to be rigorously tested for wind. We build with a lot more concrete to allow our project to withstand a greater hurricane wind load.”

Each climate intelligence platform uses different frameworks, different lingo, and certainly highly nuanced models, but there are some standardized measures and authoritative sources used by them all.

For one, both the developers and climate modelers all said they used the framework used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a division of the United Nations that compiles the latest scientific data on the climate and that predicts various outcomes based on continually updated data. The IPCC uses five different emissions scenarios to predict possible trajectories, though most companies limit it to three. At Cervest, they use the more common terms, business as usual, Paris-aligned, and middle of the road, Chopra said.

The business-as-usual scenario means continuing on the current trajectory, with global emissions still on the rise. Paris-aligned means keeping emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, which was supposed to limit global warming to no more than 2 degrees Celsius, and work to keep it under 1.5 Celsius. The middle of the road scenario is somewhere between those two extremes.

Sorkin says he calls those same scenarios “best, worst, likely” so that clients can choose what level of risk they can stomach, given the range of probabilities.

In addition, many federal agencies track specific relevant information. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) regularly updates flood maps, which are used to decide insurance rates, zoning laws, federal aid and much more. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides highly detailed weather data, wildfire maps and sea level predictions.

Jupiter uses over 100 different metrics to feed the algorithm, Sorkin said, which may be weighted by the actionable data the customer is interested in. “Some customers just want to know about their physical assets,” Sorkin said. “Some customers want to know about the external dependencies that are mission critical. Some want to know about the whole supply chain.”

Cervest also works infrastructure information into their risk ratings. “What we have today is where there is existing infrastructure that has been built for protection or adaptation, we factored that into the risk equation,” Chopra said. “What we don’t have is future looking.”

Because local infrastructure is so crucial to resilience, climate intelligence companies are looking for ways to grade municipalities on their climate resilience. This hinges on the ability and political will of cities and towns to fund necessary adaptation efforts, along with the cost of those efforts.

One potential source is through municipal bonds. “Moody’s and Fitch are taking a closer look at climate risk in city bond ratings,” ULI’s Grayson said. In 2021, Moody’s acquired RMS, a climate and natural disaster analytics firm.

In some cases, developers are stepping in to improve local infrastructure that will directly affect their properties. In San Carlos, Presidio Bay is building a life sciences development that is miles from the coast, so it’s relatively protected. It’s also sitting on a drainage creek that was originally designed to deposit storm water runoff in the bay, but has fallen into disrepair. Presidio Bay is clearing it of debris, repairing collapsed walls, and upgrading it to handle anticipated sea level rise.

While all this might seem like overkill, such physical efforts are in line with an already substantial financial toolkit to deal with natural disasters and other catastrophes, including insurance and federal emergency aid from FEMA.

The current system is not prepared to handle the anticipated onslaught of damage, however. For one, insurance is designed to handle distributed risk, so if the frequency and severity of climate disasters intensify in a particular geography, insurance companies will either raise rates to cover the exploding cost of payouts, or withdraw from the area entirely. In addition, many commercial insurance policies are per storm, not per asset, so if multiple assets are hit during the same storm, the payout won’t be adequate. Third, insurance is highly variable because it is repriced each year.

“It’s pretty scary that insurance can change year to year,” Grayson said. “If your cost of insurance doubles, it eats into profits. If you can’t get insurance, tenants can break a lease, or it can change loan terms.”

Another concern is how aid from the federal government, which is often what states turn to during disasters, will be distributed.

“It’s a challenge to predict who will be bailed out,” said Grayson. “If there’s a big hurricane, the feds get involved. But some of these smaller or localized or persistent events aren’t things that the federal government will financially help to mitigate.”

All of these factors are just beginning to impact pricing of real estate, from lending to investing to pulling out altogether in rare cases, said Arup’s Nelson.

But the market is a fickle, and malleable, master.

As in the famed exchange in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises.

“How did you go bankrupt?” one character asks another.

“In two ways,” the other character answers. “Gradually and then suddenly.”