The Tradeoff Between Carbon Offsets and Zero Carbon

By Anna Staropoli June 30, 2022 6:30 am

reprints

In Sydney, Australia, Lendlease has cut ties with carbon.

Last spring, Lendlease, an Australia-based developer, announced that it achieved carbon neutrality across its Australian office portfolio, which amounts to over $11 billion in value.

Carbon neutral, carbon negative, carbon capture: these are widely cited buzzwords throughout the real estate industry, as well as among climate advocates at large. The terms are bandied about as developers, landlords and builders commit to environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) initiatives.

Beyond Lendlease, Maryland-based developer JBG Smith (JBGS) recently announced that it had achieved carbon neutrality via offsets, while in October brokerage giant Cushman & Wakefield pledged to meet net-zero emissions by 2050.

But what exactly do these terms mean? The answer is more complicated than the vernacular suggests.

In lay terms, carbon neutral and net-zero aren’t all that different. Carbon neutral means balancing carbon emissions with means for removing them. Practically synonymous, net-zero refers to balancing greenhouse gas emissions to achieve a climate equilibrium.

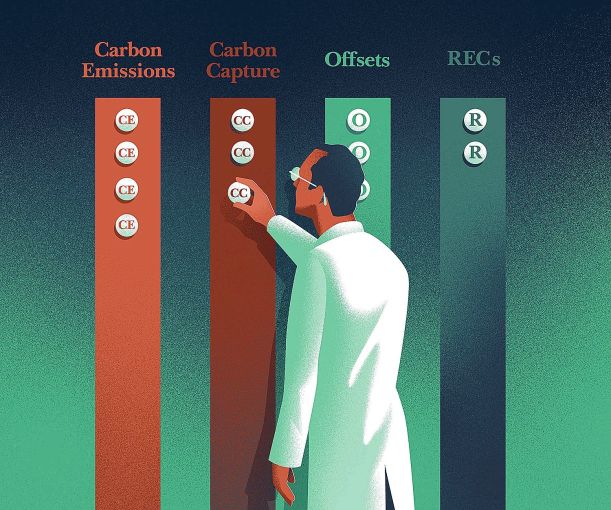

Often these balances are achieved through offsets, which compensate for emissions rather than limit them. Landlords tend to utilize offsets, at least partially, to neutralize greenhouse gas emissions from one property with the energy saved through an approved project or other property under their control. Essentially, offsets allow companies to divvy up emissions throughout their portfolios — or pay to plant trees and enact similarly pro-environmental campaigns — so they don’t necessarily need to reduce energy at any particular building. Offsets are not to be confused with the related renewable energy certificates (RECs), which companies purchase off site to add renewable energy to the grid.

Although a common stepping stone toward achieving carbon neutrality, offsets tend to be short-term fixes rather than permanent, reliable solutions.

“Our long-term goal is to be absolute zero carbon by the year 2040, which means no offsets,” said Megan Saunders, director of ESG for Lendlease Communities. The Australian Lendlease Communities also has a U.S. portfolio, which consists mostly of military housing complexes.

Tangible steps toward achieving absolute zero include switching from gas to electric, installing solar panels, and relying on efficient building systems, such as Energy Star appliances. Yet before Lendlease can reach absolute zero, the company must first establish net-zero: a goal for 2025.

And, for that, they are using offsets.

“We’re adding renewables to the grid to allow the grid to get greener,” said Saunders. “We only allow offsets for the interim goal, hence the net-zero carbon, but they will be phased out.”

Developer ShopCore Properties is likewise utilizing a hybrid model, relying on energy reductions and efficiency increases as much as possible. Corinne Rico, ShopCore’s head of ESG, sees offsets as a bridging strategy to incorporate as a last resort — and as infrequently as possible.

To see this model in action, head to the mall. ShopCore owns SkyView, an enclosed shopping center in Queens. The building, which includes not only tenant stores but also common space and a parking garage, amounts to a sizable carbon footprint, which ShopCore is addressing by installing energy efficiency upgrades and smart-building technology.

In particular, the lighting system has had a literal glow-up; SkyView is 75 percent LED. This upgrade correlates with ShopCore’s ultimate goal of making each of its properties 100 percent LED by the end of this year.

Yet due to residential towers built atop the SkyView mall, maximizing the mall’s efficiency and minimizing its energy output has proved challenging. ShopCore can’t build solar panels atop the Queens building, so the company has turned to an alternative source: Brooklyn’s Canarsie Plaza. ShopCore plans a rooftop solar installation at Canarsie, as well as rooftop parking and solar parking canopies.

“Forty percent of energy generated at Canarsie will be used to actually offset the consumption at SkyView,” Rico said.

Offset programs like Con Edison’s remote net metering, as well as community distributed generation, allow companies to play these games of balance between energy consumption and generation. Through a meter set up at Canarsie, ShopCore will measure its energy production and apply a quantity to SkyView’s bills, offsetting the energy expended in Queens with that harnessed in Brooklyn.

Offsets have become an increasingly popular strategy throughout CRE, especially with regulations such as New York’s carbon-cutting Local Law 97 looming over landlords. Yet given the urgent state of the environment, offsets may not be enough; sustainability goals are rapidly outpacing real estate’s ability to meet climate needs, requiring an all-encompassing, all-hands-on-deck approach sooner rather than later.

“The built environment, which is building and construction, accounts for almost 40 percent of annual global CO2 emissions,” Saunders said.

Indeed, real estate companies must grapple with overlapping sources of greenhouse gas emissions, each of which is responsible for some fraction of this 40 percent. Significant, recurring offenders to the built environment’s carbon footprint include the energy a building emits in its daily operations (Scope 1 and 2 emissions, in Securities & Exchange Commission parlance), which companies like ShopCore seek to reduce via solar panels and renewable energy sources; emissions coming from a company’s supply chain and third-party contractors (Scope 3 emissions); and embodied carbon.

Embodied carbon is the carbon footprint from building and construction. According to Saunders, it accounts for 11 percent of emissions worldwide — and 80 percent of Lendlease’s emissions.

Steel and concrete are largely to blame. These common building materials generate enormous carbon footprints, so if developers and landlords want to improve sustainability efforts from the ground up, they must re-evaluate their supply chains. To help its 80 percent go down, Lendlease has already begun to reassess its building process, utilizing low-carbon concrete in the construction of Chicago residential tower The Reed.

Given the scale of construction and development, not to mention the utilities used once tenants move in, it’s obvious that real estate bears a high degree of environmental responsibility. Yet rather than view the industry’s need to adapt to ESG standards as an obligation, Tammy Chernomordik, senior ESG director at Kimco Realty, sees sustainability as an opportunity.

Since 2018, Kimco’s priority has been to reduce its Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions, which refer to any emissions directly within the company’s operational control, as opposed to emissions from its supply chain or any third parties it contracts with. Examples include parking lots, corporate offices and unleased spaces. To address Scope 1 and 2, Kimco has been focusing on the common areas of buildings, lighting retrofits and building controls. But the true opportunity for landlords isn’t in those areas; it’s in Scope 3.

“Scope 3 is really anything that’s associated with your business that’s not under your direct control,” Chernomordik said.

Scope 3 emissions include emissions from construction, commuting, consultants and supplies, as well as tenant utility consumption. That last item, perhaps the most significant source of Scope 3 emissions, represents a growing problem for landlords.

Once they lease a space, tenants, triple-net ones in particular, act independently from their landlords, making partnership challenging. It’s not that tenants don’t want to reduce greenhouse gases or increase efficiency; rather, it’s that such goals remain disjointed from the building at large. Leases don’t generally allow for easy coordination or communication, making teamwork both an emergent goal and a useful springboard toward reducing carbon emissions.

“If you think about it, our Scope 3 emissions are [tenants’] Scope 1 and 2 emissions,” Chernomordik said. “So it’s really a joint effort.”

Making that effort, however, isn’t quite as simple as striking up a partnership. Data, which has rapidly become a necessity for innovation and progress, is a prerequisite to action, but Scope 3 data is difficult to collect, find and use.

“It’s a big lift to figure out how to organize [data] and track it over time in a way that is easily accessible, that you can write reports on,” said ShopCore’s Rico. She cited data as a chief difficulty in real estate’s efforts against climate change.

Kimco has faced similar difficulties, and as it looks toward the future, its goal is to set a goal: Kimco plans to decide its Scope 3 aims by 2025. Before the company can make headway on reducing Scope 3 emissions, it must first assess and evaluate the status of tenant energy consumption — a task that seems simple but boils down to a data deficit. If you don’t know how much energy a tenant is using, and in what ways, there’s little you can do to improve efficiency.

While Scope 3 data isn’t yet accessible, companies can use the interim to focus on forming those all-too-necessary partnerships. ShopCore offers on-site renewables and has created a tenant web portal to provide information about sustainability initiatives, Rico said. These achievements helped ShopCore earn recognition as a 2022 Green Lease Leader.

In addition to partnering with their tenants, developers must also consider how best to partner with anyone coming to their properties, helping people get to and from their buildings as efficiently as possible. Onsite electric vehicle charging is an up-and-coming amenity that will help decarbonize the economy and lower the environmental footprint of commuters.

“We’re not just providing space anymore to our tenants,” Rico said. “We’re providing critical energy services for our tenants to operate their business and for their customers to meet their mobility needs.”

All-consuming changes to a property — which Rico dubbed the “new frontier” for owners, developers, and tenants — require integrating smart building technology, data and sustainable ideology into business operations. Failing to do so not only poses a risk to the environment but is also an economic liability.

“We’re starting to see attitudes change, too, in the sense that inaction on climate change is starting to become a real, tangible business risk to the industry,” Rico said.

Penalties for businesses that don’t act are surely financial, including via Local Law 97’s hefty fines. But without adapting to the current environment, and adopting the best practices to save it, developers won’t be able to attract the same clientele. As the effects of climate change continue to worsen, tenants require increasingly eco-friendly buildings that will simultaneously serve as strongholds in case of natural disaster.

A building’s resiliency is therefore pivotal. Rico noted that solar panels with batteries are not only better for the environment but could also provide an alternative source of energy should a storm disrupt the grid. Likewise, battery storage systems can act as generators should the power go out.

These greener energy options present backup plans in case of disaster, representing real estate’s multipronged approach to sustainability. It’s not about achieving carbon neutrality or net-zero; rather, companies must — and are beginning to — create spaces where tenants and the natural environment are equally protected.

Anna Staropoli can be reached at astaropoli@commercialobserver.com.