The Spirit of the Year Award: David Nussbaum and David Miller

By Chava Gourarie May 17, 2021 9:00 am

reprints

This time last year, most people had never heard the term “SPAC.” Now, you’d have to be living under a rock to not know it.

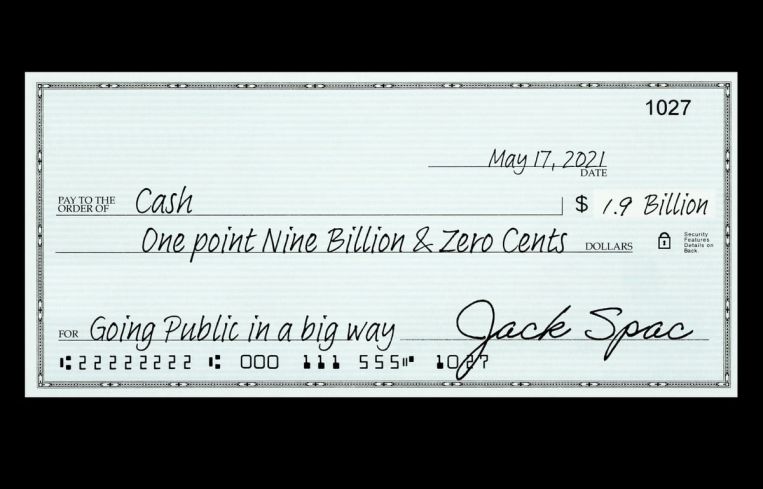

Somewhere in the midst of quarantine, mask wars, and the racking up of millions of COVID cases, an underdog financial vehicle — the special purpose acquisition company — exploded onto the scene as the hottest way for a company to go public.

But for David Nussbaum and David Miller, the SPAC is not new at all. In fact, they basically invented it. Nussbaum, then an investment banker at GKN Securities, with help from Miller, a lawyer, designed the SPAC in the early 1990s as an alternative to the blank-check companies of the 1980s, an earlier iteration that could be kind of shady.

In a SPAC, a sponsor goes public with a pot of money, then goes out in search of a company to merge with, thus taking that company public. It upends the traditional initial public offering, in which the company has to appeal to investors, rather than the other way around. SPACs thus forego much of the scrutiny that an IPO roadshow attracts, but allows the process to move much more quickly.

The SPAC had a moment in the ‘90s, but then fell out of favor after the dot-com bust. Nussbaum and Miller never gave up on their invention, though. In 2003, Nussbaum founded EarlyBirdCapital and continued to close SPAC deals, launching more than 100, and closing more than 70 mergers since.

In that time, the SPAC was largely seen as an option only for companies who couldn’t IPO the normal way, which is, in a way, a self-fulfilling prophecy. That sentiment began to change in 2020, and, as more highly regarded sponsors joined the fray, many more companies began to consider it a viable option. These changes raised the credibility of the vehicle overall.

The spike in 2020 turned into a groundswell this year, with more than $100 billion raised so far. There are currently more than 400 SPACs in search of a target, and close to 140 that have announced merger deals but have not yet completed those mergers.

Real estate is part of the wave. Institutional players, such as Silverstein Properties and Tishman Speyer, launched SPACs; so did mall giant Simon Property Group and proptech financier Fifth Wall. Not only that, but everyone’s favorite real estate “tech” startup, WeWork, plans to go public via SPAC, as well as smart-lock company Latch and short-term rental unicorn Sonder. Online real estate marketplaces Porch and Opendoor already have.

EarlyBirdCapital captured a fair share of the SPAC boom, taking on more than 30 deals in 2020 and 2021. One of its completed mergers, with Mexican homegoods company Betterware (back before it was cool) is currently the best-performing de-SPAC’d company out there.

Alas, the fun might have reached its peak. Regulators are beginning to pay closer attention to the vehicles; and, with many SPAC companies, both pre- and post-merger, underperforming the markets overall, investor appetite — especially retail investor appetite — is waning.

By this time next year, a SPAC could be just another obscure financial acronym that had its moment.