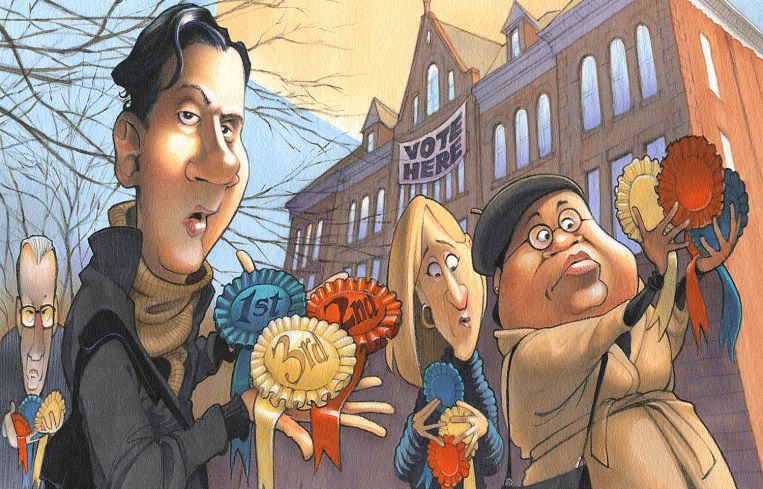

Making Heads and Tails of New York City’s New Ranked-Choice Voting System

By Aaron Short March 15, 2021 12:00 pm

reprints

Campaigning for mayor in New York is the ultimate reality show, but the city’s new election rules that decide who will come away with victory is a lot like “The Bachelor.”

It is less complicated than it sounds. The candidates are contestants seeking to woo the affections of a finicky bachelor (i.e., the registered New York City voter).

At the start of “The Bachelor,” contestants arrive at a luxury resort and mingle at a cocktail hour where they meet the show’s star. Once the evening is over, the bachelor awards roses to each person he wants to get to know better, and those who don’t receive a bud must leave the premises. Then, the flora-based elimination continues for multiple rounds until two contenders remain and the bachelor makes a decision that potentially ends in matrimony.

Scavenger hunt-based group dates and tear-jerking staged incidents of conflict aside, that’s essentially what will happen in city elections, given that New Yorkers decided in a 2019 ballot initiative to switch from a winner-take-all system to ranked-choice voting for special and primary elections.

The process has plenty of practice elsewhere in the country, most prominently in San Francisco, Maine, and Cambridge, Mass. In New York, it has the potential to swing a particularly crowded field with 33 candidates running in the Democratic primary, the winner of which is expected to win the general election based on the city’s voter registration makeup.

Given the stakes — several Democratic candidates have promised sweeping changes to zoning rules, property taxes and development requirements — it’s a process garnering increasing attention in real estate and beyond.

Under the new guidelines in New York, voters can pick up to five candidates in each race, and mark them in order of preference instead of choosing only one office-seeker. That gives people an opportunity to support multiple politicians they like and ensure that voters have more of a say in who wins public office, while incentivizing candidates to seek out constituencies beyond their backers.

“Ranked-choice is designed to have the winner be the consensus choice of the majority of the district,” Susan Lerner, executive director of government watchdog Common Cause New York and founder of Let NY Vote, a statewide initiative that advocates for voting reforms, said. “It works for the candidate who does the most outreach for the maximum number of voters. From a voter perspective that’s very positive and it’s very healthy for strengthening our democracy.”

A season of “The Bachelor” builds up over 10 weeks with time between elimination rounds, but it won’t take that long to determine the winner of the mayor’s race and other contests barring an onslaught of mail-in ballots.

That’s because the New York City Board of Elections will utilize a software tabulation program running an algorithm that calculates who wins instantaneously.

Candidates who receive a paltry number of votes, much like “The Bachelor” contestants who don’t make an indelible first impression, are lumped together based on a statistical calculation and eliminated in the first round of counting.

But the voters who picked a long-shot hopeful as their top choice won’t have their ballots thrown out. Instead, the algorithm will pluck their second-choice pick and add that vote to that candidate if they are still in the race. If that preference has been cut, the algorithm will scroll down each voter’s ranked list and tally their remainders until all votes are reallocated (for those still trying to visualize how this works and are reality show-averse — think of the Iowa caucuses without the meltdown).

“If you don’t indicate a second choice, and you vote for a candidate who gets thrown out of the ballot because they don’t do well, you don’t have a say after the first or second round,” Bradley Honan, CEO and president of Democratic polling firm Honan Strategy Group, said. “You effectively didn’t vote for mayor.”

This sorting and redistribution process will continue until a winner garners 50 percent of the vote with a combination of first and other ranked votes. But how a candidate reaches that combination is still being debated — and part of their campaign strategy.

The eventual winner is likely to have the most first choice ballots among their rivals. But it is possible for one political hopeful with an assortment of first-, second-, and third-choice ballots to edge an opponent with a preponderance of first-choice votes but few others. The strategy comes into play when candidates compete to woo their opponents’ most fervent backers to place them second or third on ballots.

Ranked-choice voting almost didn’t happen this year in New York City. The State Board of Elections delayed the certification of election software for more than a year, due to objections from two Republican commissioners, until the impasse was broken in January.

Election workers instead prepared to hand count four City Council special elections in Queens and the Bronx, if no candidate received a majority outright (one Queens race already concluded with Jim Gennaro winning 60 percent of the vote). The software is expected to be approved by April.

Several Brooklyn and Queens council members also tried to stall ranked-choice voting with a lawsuit, arguing that the new system flustered and disenfranchised voters. But a judge denied their request in December, allowing the tabulation to be used for a special election for City Council in Queens in February.

Election reform leaders believe the new system could lead to less negative campaigning and diversify who gets chosen for public office.

“In a traditional winner-take-all system, if you have more than one candidate of color in a community, that vote can fragment,” Lerner said. “It allows the candidate that most of the community doesn’t want to win, even though they are not the choice of the majority of voters in the district.”

Still, the system remains confusing to some voters three months before the primaries. Roughly one-third of Democratic voters say they don’t know enough about ranked-choice voting, while 46 percent of Black voters and 38 percent of Latino voters haven’t heard anything, an Emerson College poll released in March found.

“There is a very high lack of awareness and it’s more pronounced in low-income communities of color,” Honan said. “There could be a situation where white voters in the Upper West Side and Park Slope go down the ballot and do this, and their votes could potentially be worth more than others.”

The city has promoted how ranked-choice voting works through postcards sent to registered voters ahead of each election. The Board of Elections is adding information in its annual voter guide and candidates have received election training sessions.

But the campaign hasn’t been widespread and flyers aren’t always reaching constituents in their native language, candidates have observed. Christian Amato, founder of consultancy Consense Strategies, who is advising several council campaigns, wants the city to partner with grocery stores, community boards and business improvement districts to get the word out.

“I don’t understand why we’re not meeting people where they are,” Amato said. “We have hundreds of thousands of people giving out vaccines and these can be great places to utilize as resource hubs. Constituents should be leaving vaccination points with a piece of information on ranked-choice voting.”

Those running for office meanwhile are spending more time explaining how people should vote than discussing public policy and quality-of-life concerns.

“Right now, we’re leaving the onus on candidates to educate voters on who they should put in order for preference,” Amanda Farias, a Bronx City Council candidate, said. “People are just realizing there is another election coming. They say ‘How could there be another election when we just finished the trauma of the last election?’”