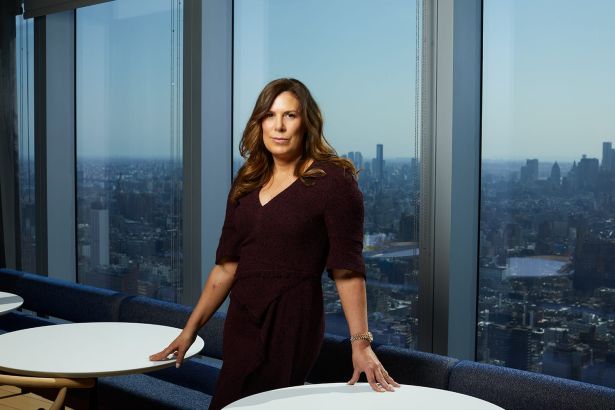

Kara McShane Talks Year One as Wells Fargo’s CRE Chief, CMBS and CLOs

By Mack Burke March 15, 2021 11:00 am

reprints

“From our perspective, it’s business as usual,” Kara McShane, Wells Fargo’s head of commercial real estate, said about the pandemic’s impact on the banking behemoth’s commercial real estate collateralized loan obligation (CRE CLO) business.

It’s hard to see where that sentiment doesn’t ring true across each of the business lines of the industry’s largest and, arguably, most influential financial institution, led by McShane, who actually quipped that her group executed “virtually, virtually flawlessly” from home amid the pandemic.

McShane “had a few weeks in the seat” at the helm of Wells Fargo’s monolithic commercial real estate practice before the onset of COVID-19, having taken over on Valentine’s Day 2020. She began to set the table for what was supposed to be a full-scale effort to make the franchise “simpler, faster and better” under a broader corporate directive that encompassed not only the CRE division, but the bank’s corporate and investment banking universes.

The pandemic, of course, forced her into an unfathomable position, having to scramble to get her arms around the entirety of the business and its people as quickly as possible.

This reimagining and transformation of the business came about two years after the bank was sanctioned by the Federal Reserve and barred from further expansion in the wake of its consumer banking scandals. Those revealed a pattern of weak internal oversight, and led to a C-suite-level overhaul that started in late 2019 with the appointment of the bank’s new CEO, Charlie Scharf, who began to reshuffle its businesses at the start of 2020.

By that time, McShane had logged a decade at Wells Fargo. She joined in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), charged with helping build out its commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and CRE CLO businesses. In just five years, those two lines grew to $67 billion from under $10 billion in 2010.

Despite the bank’s pre-pandemic push to remake itself, its CRE operation had already reached somewhat of a pinnacle. At the end of 2019, it ranked as the largest CRE lender in the U.S. in the past decade, the largest primary and master servicer by loan volume, Freddie Mac’s No. 1 bookrunner, the No. 1 CRE CLO bookrunner over the previous six years, and the second-largest real estate bonds bookrunner, globally, according to data and information from the Mortgage Bankers Association and CRE Direct.

The Commercial Real Estate Finance Council’s inaugural 2020 Woman of the Year oversaw a practice last year that kept its ears to the ground and kept humming, although McShane joked that her predecessor “timed his retirement impeccably.”

The bank’s real estate loan servicing operation — a book of $600 billion worth of business — survived tests of extreme volume during COVID, and about a third of its massive loan portfolio faced requests for customer accommodations, McShane said.

“We had roughly 30 percent of our $150 billion-plus [loan] portfolio requesting some form of accommodations,” McShane said. “They were mostly non-economic in nature, meaning they weren’t requests for payment deferrals, but the vast majority pertained to covenant waivers or property consents, allowing the property to shut down.”

Last year, Wells Fargo’s robust multifamily and agency lending businesses weren’t deterred, and the bank also executed on seven CRE CLOs, totaling nearly $5 billion, which was around half of all issuance in the market in 2020. To start this year, it’s already issued two, totaling $1.6 billion, and it’s in the market currently with another $1 billion deal, McShane said.

In November, with so many questions swirling about the future of retail and hospitality in the CMBS space, the bank executed on a $319 million CMBS refinance secured by Brookfield’s Oakbrook Center mall in Oak Brook, Ill.

Business highs, though, were met with some lows. The last 12 months were riddled with instances of personal trauma, loss and suffering experienced by so many people within her universe, which she said was a difficult thing to watch unfold in her first year and a hard pill to swallow.

McShane’s 2020 also marked the sixth year since her battle with breast cancer, a fight she said “influenced my attitude in dealing with difficult circumstances, such as the last year, and the way I show up as a leader every single day.”

COVID-19 undoubtedly mounted a war of attrition against the commercial real estate sector, but even still, it was hard-pressed to scathe a titan.

Commercial Observer: Quite an eventful first year at the helm. How would you describe it?

Kara McShane: It was certainly eventful. Like everyone’s 2020, it was incredibly challenging. Even though I had 25-plus years of industry experience, and I’ve had several leadership roles at Wells Fargo, it was still baptism by fire for me. We now know that COVID has accelerated so many trends in commercial real estate, and it did the same for me in my first year. It helped me get my arms around the portfolio much more quickly than I otherwise would have. I had to learn to lead and inspire a team that was new to me, remotely.

What needed the most attention?

We focused on retail and hospitality, initially, but we quickly followed that up with a focus on office, as we thought more about the longer-term impacts of working from home and how it will influence office demand. We haven’t seen any stress on our office portfolio to date, which is fantastic, but [they’re buoyed] by longer-term leases and strong tenants.

What about your mortgage servicing platform and the pressure it faced?

You can imagine the sheer volume of requests that we got there. We responded to more than 100,000 emails and more than 40,000 phone calls; we processed close to 100,000 tax and insurance disbursements; we provided thousands of borrower-related accommodations outside of our own portfolio; we responded to thousands of ratings agency and investor inquiries; the volume we saw going into special servicing was four to five times greater than what we had experienced in the prior year. Across the board, these were areas of extreme volume where we dedicated extra resources.

With your deep experience in the CMBS space, how did this disruption compare to what unfolded during and after the GFC?

When you think about CMBS, its recovery and resiliency, you have to consider the magnitude and speed of the Fed’s actions to inject and promote liquidity this time around, from cutting rates to unlimited quantitative easing to the new version of TALF [Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility]. All of that combined with unprecedented amounts of fiscal stimulus from the government allowed for all capital markets to rebound in record time.

As a benchmark, AAA CMBS spreads are not only currently tighter than pre-COVID levels, but they are actually at levels we have not seen since before the GFC. Last year, the tights for AAA CMBS benchmark spreads were swaps plus 76 pre-COVID, and then the new-issue market came to a grinding halt in March. We saw secondary spreads widen to 345 over on March 23 — the day before my son’s birthday, so that’s why I remember — but, by May, the new issue market was actually open for CMBS deals again. That month, AAA spreads were 145 over, and, by the end of the year, we were back to pre-COVID tights.

Just recently in the market, we hit swaps plus 61, which is a level we haven’t seen since prior to the GFC. If you think about that rebound relative to what happened in the GFC — when AAA spreads before the crisis were swaps plus 20 and they widened to as much as swaps plus 1,500 and the market was essentially frozen, with zero new issuance for 21 months from 2008 to 2010 — it’s night and day.

CMBS total volume dropped by 40 percent last year, but, by the fourth quarter, the CMBS lending market was fully open and functioning across both conduit and SASB (single-asset, single-borrower) segments.

How do you feel the CMBS market will be utilized going forward, or, maybe, where will it fit in the market? Could it capture more market share?

We’re expecting a healthy year in 2021 for issuance, albeit not quite to 2019 levels. We actually think SASB issuance could outpace conduit issuance for the first time this year, and it’s because we’re seeing institutional CRE sponsors tapping the CMBS market for both acquisitions and opportunistic refinances for large loans. And we’re seeing conduit volume struggle, so we’ve seen that dynamic and we’re predicting that might happen this year.

CMBS has survived several different forms of crises and it remains — and will remain — a resilient and important source of capital for the CRE sector. I hadn’t really thought about whether it’d increase market share. Coming out of the last crisis, we saw other forms of capital rise up to supply financing for the market over the past decade, and the CMBS market shrinking over time and kind of stabilizing. Coming through this crisis, we might actually see a slight uptick.

I don’t think the market share for CMBS will drop in the future, but going forward, we’ll see it increase and stabilize around the levels we saw pre-downturn. People have had a better experience this time around; master and special servicers are working with borrowers through the pandemic, and it’s going to promote many borrowers to be repeat clients in the CMBS space.

What gave you the confidence to know that you’re going to have enough investor demand to execute CMBS deals in an environment like last year’s?

It’s years of experience in the space, but you also take your cues from other markets. You had to look at what was going on in the equity market and in the other debt capital markets. Just thinking about the time of recovery, you saw the corporate bond market come back much more quickly than that CMBS market, and you saw other bond markets come back prior to the CMBS recovery. So, we were actually last to the party, and you gauge the sentiment; you could tell there was a shift from risk-off to risk-on sentiment.

You could also see that as other sectors were recovering, and spreads were tightening in other sectors, and equity markets were rallying, investors started to feel afraid that they were going to miss the buying opportunity. I think that was the shift that took place. And, when you go out to market with a deal, you look at where bonds are trading in the secondary market and where other sectors are trading, and you think about relative value of your new-issue bonds to other investment opportunities for these investors; that’s how we gauge or determine where we’re going to go out with price guidance.

If you get it right, great. If you’ve been too conservative, then you might get a lot of oversubscription and spreads tighten; and if you get it wrong, the spreads have to widen out to clear the bonds.

How was investor interest in the higher-yielding bond space amid so much uncertainty?

I think throughout the crisis there continued to be a lot of capital in the CMBS B-piece space, dominated mostly by the same platforms. Many B-buyers raised fresh funds pre-COVID and are still sitting on large amounts of capital to invest. The B-piece market remains one of the few places to generate significant yield in the CRE debt market. There’s a lot of capital available for all types of risk retention structures on the B-piece side as well. You put all that together and you think about the lack of supply that existed in the conduit market last year. There were few deals coming to market and B- buyers had a lot of capital, so that supply-and-demand dynamic was beneficial for the market.

Even with that dynamic, and the fact that there is a lot of capital chasing a limited amount of B-pieces, these buyers remained disciplined from a credit perspective throughout the crisis, and even today. They had an opportunity to buy deals at a wider yield level during the crisis and that’s really come back to pre-COVID levels.

Will hotel and retail ever return to CMBS conduits in a meaningful way?

The lack of hotel and retail originations has been a key driver for the declines on CMBS issuance. Pre-COVID, hotel and retail, on average, accounted for about a third of every conduit deal issued. Post-COVID, that number stands at 18 percent, but there’s a qualifier: it’s driven mainly by a large casino hotel [MGM Grand & Mandalay Bay] that was originated pre-COVID and has been securitized across a number of transactions over the last eight months.

New hotel origination has largely been absent from the CMBS market since March. We are starting to see a limited amount of hotel CMBS origination occur on smaller, limited-service hotels with observable demand drivers, moderate leverage and reserves in place. We believe, as the recovery progresses and with a successful vaccine rollout, that there will be a great opportunity to lend on hotels. We expect to see more transaction activity and recapitalizations in the space, and we believe that it’s actually one of the last sectors where we will be able to find good value at attractive leverage points, structure and pricing. It’s happening now.

On the retail side, we never saw retail lending in CMBS shut down entirely. Activity is focused on needs-based retail, such as grocery-anchored retail and higher-quality, single-tenant properties. Leverage levels have remained low — in the 55 to 60 percent range. And then, obviously, malls or power centers and other weak-tenanted retail, that lending has largely shut off. We recently securitized a large, high-quality mall, and we do expect to see more mall activity in 2021, as the number of malls that were securitized pre-GFC are maturing and coming due, and they’re going to need to find a home.

If it’s a fortress mall, Class A, high sales per square foot, then that’s certainly something investors can get their arms around. A third mall in a two-mall town, that’s not going to happen.

People aren’t just focused on tenant stabilization, but more so the sponsor, the operator, the location, sales, history and what the future looks like, including the tenant base. Also, do the owners and operators have the capital to invest in repositioning their properties if necessary? The key is adaptability and capital availability.

What are your thoughts on how your warehouse business shook out last year?

The loan warehouse business is absolutely critical to our commercial real estate franchise, and we remain completely committed to the product.

We have about $20 billion of commitments, with roughly half of that outstanding in our loan repo book. We think the warehouse business offers an attractive risk-adjusted return, and it’s an important product for our non-bank lender clients. Our loan warehouse business has remained fully operational throughout the crisis and we’ve seen increasing activity since the fourth quarter.

Currently, our clients are very active in the bridge space. We’re seeing competition heat up quickly and spreads tighten on underlying loans. The activity has largely been in the multifamily sector, but there is activity across all property types. We remain a leader in the CRE CLO space, and we are agnostic as to whether our clients access the capital markets or not. We like the risk we take on our warehouse lines, and we’re more than happy to keep those loans on our balance sheet. We don’t approach the warehouse business as a simple bridge-to-securitization product, so, therefore, we don’t force our clients to ultimately finance through a CRE CLO. If they choose to do so, we have that expertise and we’re more than happy to take them to market, but it’s certainly not a requirement.

Last year, we saw the underlying loan activity of the clients we finance basically shut down during that process, so we remained open throughout the sector, but we weren’t getting new requests on the lines. But, that portfolio has performed well, and, if anything, I think the crisis just confirms the viability of that model.

Do you think leveraged lenders learned anything from being hit by margin calls that came from the pandemic? Or was there a broader takeaway or lesson for those that faced that pressure?

If leveraged lenders learned anything during the pandemic, it is that highly leveraging securities — bonds and, particularly, lower-rated securities — with mark-to-market financing can be a dangerous business plan in times of severe market disruption. Those that got into trouble this time around were the ones that engaged in that activity in addition to their normal, whole loan or lending activity.

The lending community, generally, remained disciplined throughout this cycle. I don’t think leveraged lenders really got offsides pre-COVID; leverage remained in check, and lenders chose to compete more on price as opposed to structure or leverage. So, going forward, leveraged lenders will be selective about business plans and the assets they finance as the market recovers. I think those lenders need to be careful about retail and hotel, as those sectors work through issues, and stay thoughtful about rents and leasing activity in office as corporate America rationalizes its office space needs.

Wells is a CRE CLO market leader, but what do you make of its growth at the end of last year and at the start of this year? Will this continue?

We just had to deal with lower volumes. It was down around 55 percent year-over-year from 2019; issuance was $8.7 billion in 2020, versus $19.2 billion in 2019. The market’s off to a strong start this year, with a very robust forward pipeline through mid-year, so volume predictions for this year are as high as $23 billion, which would be a post-GFC high. Demand for CRE CLOs has been strong. There’s been a positive supply-demand dynamic, like in CMBS; there’s been a lack of availability of secondary bonds as historical deals have refinanced; we’ve seen increased demand for floating-rate paper as interest rates have risen a bit; some are concerned about inflation taking hold.

CRE CLOs have proven to be extremely resilient during COVID, mostly because of the sponsor equity retention and the alignment of interests, coupled with higher subordination levels and transaction structural features this time around. We’re dealing with all underlying whole loans and issuers that are holding their equity, so you have that alignment of interest, which is very different from the last cycle, when you saw arbitrage vehicles.

Issuers are the first loss, the equity in all the deals, so they are aligned with the bond investors from a risk perspective, and they want to protect their equity and they’re going to do what they need to do to protect [it]. And the bondholders are obviously protected before the equity. So, that incentive is very different from the last cycle, when issuers were securitizing and then cashing out. For them, it was an arbitrage vehicle, where they were collecting an asset management fee, and it was a way to accumulate assets under management and earn money; the motivations were different.

This time, it really is a financing tool and it’s not that different than financing on a warehouse line, with the exception that it’s match term and non-mark-to-market.

This story was updated to clarify the bank’s loan servicing portfolio against it’s separate loan portfolio.