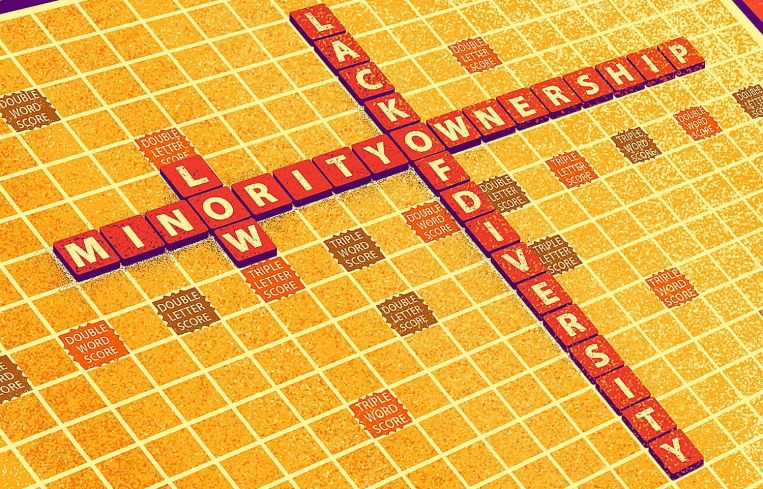

Diversifying Commercial Real Estate Boardrooms Collides With History

Finally diversifying commercial real estate’s topmost panels means more than convincing stakeholders Black lives matter, experts say

By Adam Bonislawski March 29, 2021 3:00 pm

reprints

When you picture the boardroom of a commercial real estate firm, diversity probably isn’t the first thing that comes to mind.

That’s for good reason.

An analysis published last year by Bisnow found 96 people of color among the roughly 700 board members at 68 commercial real estate companies. A 2019 study by Bella Research Group and the Knight Foundation found that just around 2 percent of commercial real estate firms are minority-owned, with another 2 percent women-owned.

Might we, though, be in the midst of a shift in thinking that could bring more minority presence to the industry’s boardrooms?

It’s typically unwise to go all Pollyanna on such questions, but there are a few indications that — in the wake of social movements like Black Lives Matter and the George Floyd protests, and the evidence of the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate impacts on minority communities — pressure is growing within the industry, and outside of it, to diversify its corporate boards.

For instance, in December, Nasdaq proposed new listing rules that would require all companies on its U.S. exchange to publicly disclose statistics on their boards’ diversity levels, and require most listed firms to either have two diverse directors or explain why not.

In its 2020 report, the New York City Employees’ Retirement System noted that it had influenced 20 companies in which it has holdings to adopt policies that require consideration of diversity when searching for new CEOs and board directors.

Also last year, California passed legislation requiring publicly held companies operating in the state to have at least one board member from an underrepresented community by the end of 2021.

And, in its most recent investment stewardship report, asset management firm BlackRock said it is “increasingly looking to companies to consider the ethnic diversity of their boards, as we are convinced tone from the top matters as companies seek to become more diverse and inclusive.” The report noted that, in 2020, BlackRock voted 1,500 times against the managements of companies it invests in due to “insufficient diversity” on their boards.

None of these developments are specific to the commercial real estate industry, but all could impact a number of firms in the space. They also demonstrate growing emphasis within the business world on diversifying corporate boards.

“In the environment of the past 12 to 24 months, certainly there are more companies recognizing that maybe they have been slow to take up diversity as a value at all levels,” said Ken McIntyre, CEO of the Real Estate Executive Council, a trade association for minorities in the commercial real estate industry.

Last year, McIntyre joined the board of Newmark Group. This year, he joined the board of real estate investment firm Acadia Realty Trust.

“In the past year, clearly, COVID’s disproportionate effects on communities of color, and then the George Floyd incident and other racial injustices and, of course, people marching in the streets and all of us being home to see those events has brought it to the front burner,” he said. “And, so, all companies now have had to have the discussion about where they are on diversity.”

Will those conversations continue after the public’s focus moves inevitably to other topics? Certainly, firms themselves don’t seem overly anxious to discuss the issue. Of the half-dozen large commercial real estate companies contacted for this story, none were available for an interview.

“I think there are some firms who have fully embraced it,” McIntyre said. “But, I do think that there are some firms who will only continue to act if their external constituents require them to. And those constituents could be shareholders, they could be tenants, they could be potential employees, they could be funding sources.”

He pointed to developments like the new California legislation and BlackRock’s comments in its stewardship report as indications of the kind of outside pressure commercial real estate firms will likely continue to feel.

“Speaking as a board member, boards have been sensitive to how their companies are rated with respect to the environment, how their companies are rated with respect to governance. And now I think most board members realize that it is just a matter of time before the pension funds and institutional investors and retail investors that own the common stock of these companies start to focus on diversity,” McIntyre said.

In terms of board diversity, commercial real estate has lagged the already unspectacular performance of the U.S. corporate world at large. According to the 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, 22 percent of directors at companies in the S&P 500 are minorities. (The previously cited figures from Bisnow suggest that figure is around 14 percent for commercial real estate.)

One factor contributing to the industry’s slow progress on the issue is likely the fact that the business is not as public facing as other sectors, and so has not felt as much pressure to diversify, said G. Lamont Blackstone, principal at real estate consulting firm G.L Blackstone & Associates and chairman of Project REAP, an organization aimed at boosting diversity in commercial real estate.

Another could be the fact that boards are relatively new to the commercial real estate scene, said Collete English Dixon, executive director of the Marshall Bennett Institute of Real Estate at Roosevelt University.

“A lot of private companies just had little advisory boards,” she said. “That was just a bunch of friends you got together at the golf course to talk about what you were going to do.”

Dixon said the public company model began to proliferate throughout the commercial real estate world with the rise of real estate investment trusts (REITs).

“So, you are talking about 20 to 25 years ago, and many of the people who were on those boards … were predominantly white males,” she said.

For those inclined toward optimism, this could present an opportunity. Many who joined boards during that initial wave of formation are likely now approaching retirement age, which could mean a number of seats opening up. If the current emphasis on board diversity informs how those seats are filled, it could accelerate the process of bringing underrepresented voices to these bodies.

“It may be a great combination of time and place,” Dixon said. “Opportunity is crossing over with what is going on timing-wise with public [commercial real estate] companies, REITs, and their board evolutions. And, also, you have a growing pool of diverse talent that is bringing to the table the same kind of experience, and maybe even better experience, than that first round of board members.”

And, while some of the current focus on diversity is no doubt a reaction to the high profile that issues like racial justice have attained over the last year, the hope is that by increasing board diversity, companies will ensure an ongoing commitment to the idea.

“It has ripple effects,” Dixon said. “That diversity of thought in the boardroom will wind up having the opportunity to influence decisions the company makes about talent. It’s a complementary and virtuous circle.”

“From my experience, it is the exception that somebody gets onto a board, where they are not known to at least one or more of the board members or senior management,” McIntyre said, speaking to the importance of social and career networks in board selections.

Of course, the ultimate development that will drive the diversification of boards, and workplaces more generally, is companies embracing the notion that diversity isn’t just good politics — it’s also good business.

“The whole concept is not sustainable unless you believe it is more than just the right thing to do,” Dixon said.

“The invisible power of diversity is that every organization needs talent, and if talent of color goes to your website and does not see people of color in leadership positions, then you will never be able to measure the opportunity cost from a talent perspective that that optic is costing you,” McIntyre said. “Having a diverse board gives all of the talent potentially coming into your organization the idea that they have a shot. And that gives you as a company the opportunity to benefit from the broadest group of talent possible.”

It also gives an organization opportunities to see pitfalls, and opportunities [that] a more homogenous board might miss, Blackstone noted.

“If you’re sitting in a boardroom and everybody thinks exactly the same because they are all 50-plus-year-old Caucasian males, I suppose that is great, if they all happen to be right,” he joked.

Blackstone highlighted research done by McKinsey & Company looking at the relationship between the diversity of a company’s leadership and its performance. In 2018, the consulting firm put out a report finding that companies in the top quartile for ethnic and cultural diversity had a 33 percent greater likelihood of outperforming their peers financially. Firms in the top quartile in gender diversity had a 15 percent greater likelihood of outperforming.

He suggested that such findings could be driving companies’ move to diversify their boards, though he added that he was “not by any means suggesting that this is the dominant influence.”

Generally speaking, Blackstone said the evidence that the commercial real estate industry has come to understand the edge diversity can give a business remains spotty.

“That doesn’t mean it’s not happening, but I have not seen enough that commercial real estate organizations are reacting that way,” he said. “But, my point is this: Diversity can, and will, be a value proposition.”