The 1918 Flu Pandemic’s Effects on New York City

REBNY’s on its second pandemic in New York. The last one left behind radiators and rent control.

By Nicholas Rizzi January 26, 2021 3:23 pm

reprints

It might be hard to believe, but New York City and the Real Estate Board of New York have been through this before.

In 1918, amid a world war, the United States and Europe also fought a deadly influenza pandemic that ranks among the worst in history. The virus hit New York on Aug. 11, 1918, when a Norwegian ship with 100 passengers sick with the illness docked on the city’s shores.

The vessel, named Bergensfjord, was met with a reception of ambulances and health officials who transported the infected to a hospital in Brooklyn, The New York Times reported. But more kept coming, with other liners from France and the Netherlands carrying passengers sick with the virus to the city.

Even though the pandemic — which lasted for about two years — started in March 1918, it became particularly deadly toward the latter end of the year, because of a “second wave” caused by a mutated strain of the infection spread by soldiers returning from the war, according to historians.

All told, an estimated 20 million to 50 million people lost their lives to the influenza virus, more than the total loss of life during World War I. And, while it eventually got the name “Spanish Flu,” that’s only because Spain didn’t suppress news of the virus like other countries did, said New York City historian Kevin Draper. It’s still unknown exactly where the virus originated.

“It’s just because they admitted it and tried to really do the right thing,” Draper, who runs New York Historical Tours, said. “It was pretty bad all over the world.”

While the virus touched down in New York in August, its first recorded death in the city was on Sept. 15, 1918, and it hit hard the next month, according to NYT. And, by October, the city was seeing nearly 4,000 new cases a day with a daily death rate between 400 to 500. New York City had about 30,000 total deaths from three waves of the virus, with 20,000 of those in the fall of 1918 alone, according to a paper in the medical journal Public Health Report.

However, unlike some people today claiming that the coronavirus pandemic is a hoax and refusing to wear a mask inside a grocery store, the general sentiment in the city during the 1918 pandemic was to defer to scientists on how to limit the spread of influenza.

“Overall, people in politics, and the [city], did listen to science and they did listen to the so-called professionals,” Draper said. “Science and technology were really changing the world. People believed in it.”

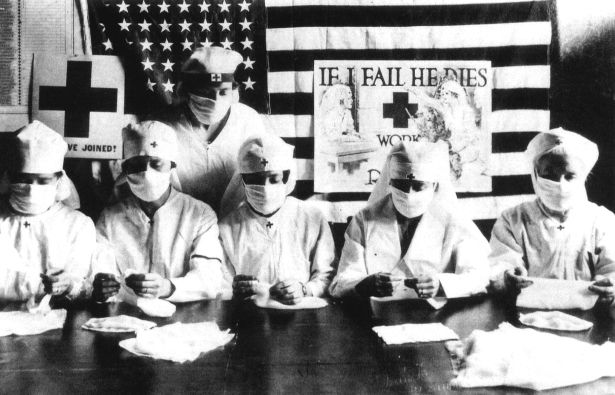

Photos from that period of time show police officers, barbers, street sweepers and residents donning masks to prevent the spread of influenza. More people wanted to wear masks at the time, but they were much harder to come by than today.

“One of the biggest things people understood was social distancing,” Draper said. “Anti-common sense wasn’t as promoted and wasn’t as common.”

The architect for New York’s pandemic plan at that time was Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland, who made a series of sometimes controversial decisions aimed to curb the spread of the virus. Since New Yorkers in 1918 lacked the ability to fire up a laptop and tune in to a Zoom meeting for work, the majority of offices and factories remained open during the pandemic, according to Draper.

“They tried to keep businesses open and running,” he said. “They didn’t quite realize how quickly these things could spread.”

Yet, Copeland did take measures to limit the number of people cramming into factories, offices and subway cars. He worked with business owners to create staggered work shifts for people and avoid rush hours. Offices remained opened from 8:40 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. while wholesalers started earlier and manufacturers started later, according to NYT.

Another notable strategy from Copeland was to create more than 150 emergency health centers across the city to ease the burden of hospitals treating infected patients, according to PHR. Gymnasiums, armories and homeless shelters were converted to treat the sick, and the city also relied on at-home care for some.

The city installed posters all around explaining how the virus was spread and telling residents to cover their coughs and sneezes in public. Copeland also took on another unsanitary public behavior: spitting. He even allowed police officers to slap $1 fines on people caught in the act, according to NYT.

Not every one of Copeland’s moves received a warm greeting. He came under fire for refusing to shutter schools and theaters throughout the city. Copeland reasoned that schools were cleaner and safer than many homes in the city — especially tenements. He also figured teachers could provide education on how to limit the spread of disease and students could be given a daily medical exam, according to PHR.

In a time before home televisions, Copeland also wanted to keep theaters open, so the city could use them to disseminate information to residents about the viral illness. However, he required theaters to open all of their windows and doors off-hours to ventilate and limit the number of people inside.

While some of his methods were questioned, Copeland’s strategies rewarded the city with a relatively low fatality rate from the virus compared to other cities, according to PHR. The city’s death rate was around 4.7 deaths per 1,000 people, lower than Boston’s 6.5 per 1,000 people and Philadelphia’s 7.3 per 1,000 people.

And, because theaters, restaurants and offices weren’t forced to shut down like the current coronavirus pandemic, the real estate industry wasn’t hit as hard as it is today, Draper said.

“The fact [that] they didn’t do that … you’re not going to have the negative effect on the real estate industry,” Draper said. “The fact that industry kept going meant they kept paying rent.”

That didn’t mean the economy was all rosy in the city. People were still afraid to frequent bars and restaurants and mostly stayed confined to their homes whenever possible, Draper said.

The wholesale and retail traders were especially hit hard by the pandemic, and mills were forced to close. Employment fell between 7 to 15 percent, too, according to a report from the National Bureau of Economic Research. However, all recovered by the end of 1919.

For its part, REBNY, which was then in its third decade, was focusing much of its efforts around the time of the pandemic on winning changes to the city’s zoning laws, something that became especially important once the pandemic finally waned, Draper said.

“It could tie your hands on how you develop and how you build buildings,” Draper said. “[REBNY] wanted you to be as free as possible.”

Toward the end of 1919, the pandemic started to subside — not by a vaccine — and focus shifted to soldiers returning home from World War I. They needed places to live and raise a family.

“A lot of these guys got married, a lot of these guys had kids, so we had an increase in our population,” Draper said. “And, with that, you need more housing and more stuff.”

That, along with a surge of new immigrants, helped lead to the Roaring 20s, which included one of the biggest real estate booms in the city’s history and meant developers were scrambling to build as much housing as they could, Draper said. The city’s population grew by nearly 18 percent from 1910 to 1920, from 4.7 million to 5.6 million, according to census records. And there was a huge jump in housing construction — especially in the second quarter of 1926 — to meet that demand, according to a Fordham University research report.

Along with the post-pandemic real estate boom came something real estate developers didn’t care for — and still complain about.

Early in 1918, New York City was dealing with what Mayor John F. Hylan called the worst crises in its history: a coal shortage, according to American urban historian Robert M. Fogelson’s 2013 book, “The Great Rent Wars.” Working-class residents stood in line all night waiting for lumps of coal, and riots erupted in Williamsburg and Brownsville, Brooklyn, after coal yards ran out. Thousands died in their cold apartments, and many were already dealing with rent climbing 33 percent from 1917 to 1918.

Combined with a deadly pandemic spreading through the city and the masses were ready to revolt. Rent strikes hit the streets more than ever before, which eventually led to rent control laws coming into effect in the 1920s.

And, for any New Yorker who’s ever been awoken in the middle of a night by the loud banging of your radiator that makes your bedroom feel like Florida in August in a matter of minutes, you have the influenza pandemic to blame for that as well.

Health officials were especially concerned about the spread of disease in the wake of that pandemic and realized that fresh air was an effective method for limiting the spread of airborne viruses, according to Bloomberg. That remains true in the winter, but New Yorkers generally weren’t too keen, just like now, to throw open their windows in the middle of January.

So, steam heating and radiators were designed to keep dwellings warm enough inside so that New Yorkers could keep their windows open during the coldest days. Currently, about 80 percent of apartment buildings in the city still use steam heat.

While, hopefully, we don’t stick future generations of New Yorkers with something as unbearable as steam heat after the current coronavirus outbreak passes, Draper does anticipate another Roaring 20s in the city’s future.

“Everybody I talk to thinks we’re going to have a Roaring 20s coming up,” Draper said. “Everyone just has this pent-up desire.”