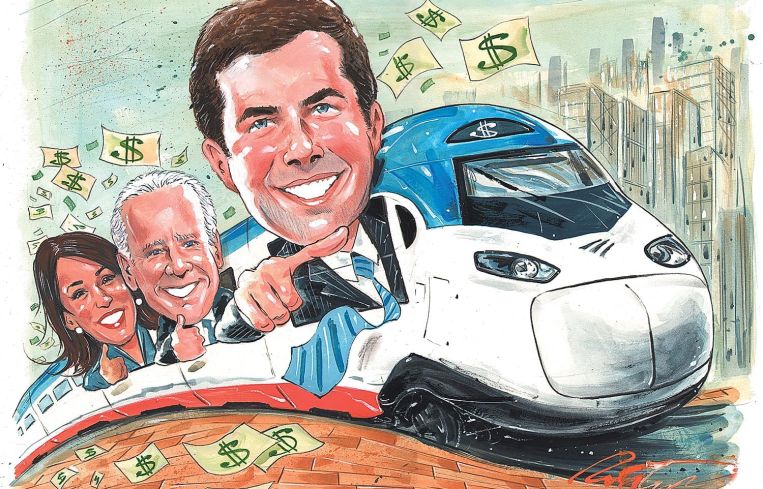

All Aboard the Infrastructure Express: Financing Biden’s Wishlist

While Biden might not get everything on his infrastructure wish list, paying for it through public channels seems to be a realistic way of setting the foundation for robust, long-term growth in the U.S.

By Mack Burke January 19, 2021 2:00 pm

reprints

Infrastructure investment has long been a target of U.S. lawmakers as a way to make a direct, material impact on the long-term growth potential of the country’s economy.

From transportation to utilities, the country’s infrastructure has been neglected and is in dire need of investment.

“We do not need just band-aids on lacerations,” JLL Chief Economist Ryan Severino said. “We’ve been underfunding our infrastructure by $5 to $6 trillion. There should be no stop-gaps, but rebuilds — airports, telecommunications, rail stations and things like that; there is no corner of infrastructure that’s not being neglected right now. My thought is — fingers crossed — they’ll be able to get some work done, but I thought that about the last administration.”

President Donald Trump was unable to significantly move the needle during his term, even at the onset, with the backdrop of a Republican-controlled Congress. But, last November, his successor, President-elect Joe Biden, released a rough outline that showcased a monumental, roughly $2.4 trillion campaign that would pour gobs of money over a 10-year period into traditional and non-traditional, or more modern, areas of infrastructure. It represents about a third of the nearly $7.3 trillion overall economic spending plan Biden wants to deploy during his term.

The mission is to overcome the nation’s infrastructure challenges, while simultaneously tackling climate change goals in an attempt to make the country more energy efficient and reach net-zero emissions by 2050 — and while also providing a more robust level of connectivity to businesses and the American people through 5G and rural broadband.

Biden’s administration will likely follow a blueprint of previous Democratic administrations when it comes to funding, which would revolve around the federal government taking a more active, leading role in facilitating financing for these projects, as opposed to leaning on public-private partnerships to make it happen.

Economists who spoke with Commercial Observer anticipate that sweeping tax changes will be instituted and a bevy of government spending will be approved to bring the new administration’s infrastructure — and economic — plans to fruition over the course of the next decade. Given the state of the economy, the timing for finally rebuilding the U.S.’s crumbling infrastructure seems right.

“It’s an age-old argument we find ourselves in,” Severino said, “that you tend to see Democratic administrations trying to lean more towards relying on public sources and Republicans more on private sources. The biggest hangup we’ve had is thinking about how we’re going to finance this.”

Biden first needs to get control of a surging COVID-19 pandemic before he can advance funding for his infrastructure proposals, Severino said. Such a move would not only cure the public health crisis, but boost the economy and put people back to work, thus bolstering tax revenues that could help cover the infrastructure costs.

It still remains a tall order nearly a year after the pandemic hit.

First-time jobless claims in the first week of 2021 beat estimates and reached about 965,000, the highest figure since last August, according to U.S. Department of Labor figures released last week. The unemployment rate remained unchanged at 6.7 percent in December, down significantly from the record high of 14.7 percent in April 2020, the highest level since the government started collecting the data in January 1948.

Just last week, Biden proposed an immediate injection of $1.9 trillion to jolt the economy and combat the COVID-19 crisis. That includes a combined $750 billion in support of state and local governments; pandemic mitigation efforts and the vaccine rollout; as well as more direct support for the American people via $1,400 payments, and in other areas, such as unemployment benefits, paid leave and subsidies for child care.

Biden’s broader, roughly $7.3 trillion spending plan for the economy — called “Build Back Better” — if fully enacted under a Democratic-controlled government, is estimated to create 18.6 million jobs and return the economy to full employment (a projected unemployment rate of 4.1 percent) by the second half of 2022 or early 2023, per Moody’s Analytics. With that, the average American household is projected to see a nearly $5,000 jump in annual income after taxes.

These policies would lead to average annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth of about 4.2 percent from 2020 to 2024, due to aggressive government spending early on, and 2.9 percent average growth throughout the decade, per Moody’s analysis.

The plans would be kickstarted further by unwinding Trump’s tax policies enacted in 2017 as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, including raising the top marginal corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent — Trump cut it from 35 percent to 21 percent in 2017 — and hiking taxes on individuals who are reeling in more than $400,000 per year. There would also likely be tax incentives provided to companies for doing business and hiring domestically and penalties levied on companies that manufacture and import products from overseas.

“The bigger, long-term implication from [the Georgia Senate runoffs] is now Democrats, under Biden, can pass, through budget reconciliation, some major changes to spending and taxes,” said Moody’s Economist Bernard Yaros.

The reconciliation process would require just a simple majority in the Senate — rather than the 60 needed to avoid a filibuster — to pass the legislation into law. Yaros said he assumes that through this reconciliation process, Democrats will pass tax and spending changes at the end of this year, which will start to be implemented in early 2022, just ahead of when Moody’s expects the country to be near full employment.

“[We expect to see] infrastructure and social benefits in 2021, assuming corporate taxes aren’t increased until 2024 to give breathing room for the economy. The stimulus is front-loaded to not have any fiscal offsets, and by 2024, the economy should be at or on its way to full employment and can sustain tax increases on corporations and wealthy individuals,” Yaros added.

These building blocks would lead to the potential for a remarkable pool of tax revenue of about $4.1 trillion — more than half of which would come from corporate income taxes — over the course of the decade, offsetting costs for instrustrure and social safety net benefits.

But, a bulk of Biden’s economic plan will likely be deficit financed, according to analysis and projections from Moody’s Analytics. The U.S. budget deficit would be $2 trillion higher in his first term and $2.6 trillion higher by the end of the decade under Biden’s proposals.

The current low-interest-rate environment, however, has created a somewhat ripe moment to take on a larger government debt load to finance infrastructure goals. The Federal Reserve’s zero-interest-rate policy, which Moody’s expects to remain mostly constant through Biden’s term in office, will work to mitigate “the macroeconomic consequences of the larger budget deficits.” The funding would be front-loaded, waning over the course of the decade, as his policies wind down and the economy ramps up and employment increases.

“The rate of return on these investments is higher than interest rates,” Yaros said. “I don’t want to say spending on infrastructure gets paid for 100 percent, but with low interest rates and the jobs and the tax revenue created, it helps pay for the infrastructure that the federal government would be financing.

“Given that the job market will be utilized and the Fed will be wary of raising interest rates, it’s a cost-effective time and place to do it … and it’s a cost-effective way to stimulate the economy,” Yaros added.

The massive $2.4 trillion infrastructure spending proposal is the largest piece of Biden’s $7.3 trillion in proposed spending during his term. Most of that infrastructure spending will come during his term, and then will extend out through the rest of the decade. It includes $900 billion for transportation infrastructure; $700 billion will be dedicated to the federal government buying goods and products made by American workers, such as clean vehicles and medical supplies, and to also fund research and development into 5G, artificial intelligence and biotech; $490 billion will go toward a bevy of clean-energy initiatives; and the remaining $300 billion will cover other infrastructure projects, such as affordable housing, rural broadband and the modernization of schools, among other projects.

“I don’t think Biden’s going to get everything on his wish list — none ever do,” JLL’s Severino said. “And I don’t think the de facto majority in the Senate will allow them to do this.”

With so much to do, where does it begin?

Yaros pointed to roadways as a likely starting line at the end of the year, when lawmakers might move to extend the Obama-era Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, which is set to expire on Oct. 1. (A year-long extension to the program was included in the September 2020 temporary spending bill.)

And, as it relates to funding traditional infrastructure — roads, rail and ports — the government, through the Department of Transportation (DOT), can do that through a variety of avenues, such as public financing via Tax Increment Financing (TIF); the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) lending program; and from grants provided through the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) program, which has provided $9 billion to 678 projects located in every state, district, territory and colony (aside from American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands) across 12 funding rounds since 2009.

In December, Pete Buttigieg was tapped to head DOT, which will be in charge of spearheading the deployment of the largest pool of funds included in Biden’s infrastructure proposal.

Buttigieg has been lauded for his work in rebuilding South Bend, Ind.’s infrastructure in his eight years as mayor, albeit on a much smaller scale. It’s worth noting, too, that when he was running for president, Buttigieg did not put much significance on public-private partnerships for funding infrastructure improvements.

Severino said in relation to Biden’s infrastructure funding plan that “there’s a logic to it that works … but if they’re going to be serious about it on the scale they’re talking about, it’s going to require a diversity of sources — some from taxes, some from debt, some from private channels, and then state and municipal sources. The scale is so grand that it seems improbable to me that the cost can be laid to one group, specifically.

“What gets lost is not public versus private, but the relationships between the bigger players, like the federal government and state and municipal governments,” Severino added, alluding to an idea that the new administration might run into problems with lawmakers from red states who aren’t so keen on heavy deficit spending.

Yaros said there’s “some potential for [public-private partnerships], but given the tack Democrats have taken, this will rely on direct funding to state and local governments.”