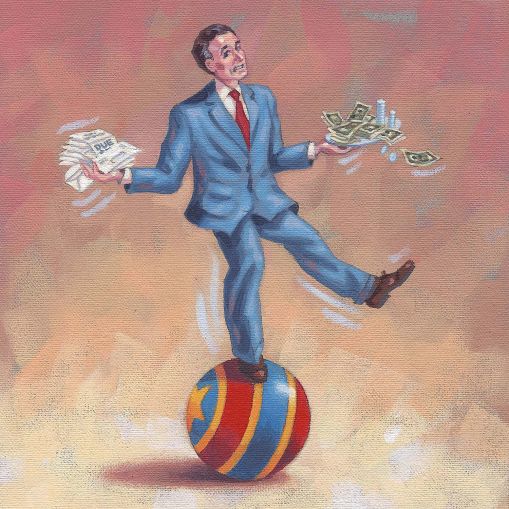

Striking a Balance Between Tenants, Landlords and Lenders

By Adam Bonislawski April 10, 2020 4:32 pm

reprints

The effects of the coronavirus have begun to ripple through the commercial real estate world. Last month, restaurant chain The Cheesecake Factory made waves with the announcement that it wouldn’t be paying April rent. Sandwich maker Subway similarly informed its landlords that it might not make rent payments due to government-enforced shutdowns. As Commercial Observer reported, a recent Fitch Ratings report found that as of March 29, more than 2,600 commercial real estate borrowers representing over $49 billion in mortgage loans have sought debt relief due to the outbreak.

On the surface, the problem the COVID-19 pandemic poses for real estate is straightforward enough. The outbreak has shut down large swaths of the economy, which means many people and businesses can’t pay their rent. If they can’t pay their rent, building owners can’t pay their mortgages. And if building owners can’t pay their mortgages, debt holders won’t receive what they are owed.

The tricky part is figuring out what, exactly, to do about the situation.

For landlords, it’s generally in their best interest to keep their current tenants in place, suggested Adam Henick, co-founder of commercial brokerage Current Real Estate Advisors. That’s particularly the case given the challenges of finding new tenants in the middle of a multi-state shutdown.

“Landlords want to be able to get through this with their tenants in place rather than trying to find a new tenant when no one is even allowed to go tour spaces,” he said.

“You don’t want to have to go through the process of re-tenanting space, which generally involves an incremental investment,” agreed Michael Maturo, president at RXR Realty. “From a landlord standpoint, you want your tenant to get back in business as soon as we get the all-clear. So I think it makes a lot of sense for landlords to work with those [tenants].”

It isn’t entirely up to the landlords, however.

“The majority of a landlord’s revenue goes to pay their mortgage, their taxes, their utilities,” said David Schwartz, principal at Slate Property Group. And so plans to offer rent deferment or forbearance will require coordination between several different parties.

Aaron Appel, senior managing director with commercial real estate finance firm Walker & Dunlop, said that, generally speaking, it wasn’t in lenders’ interests to take a hard line, either.

“Everyone understands that this is a challenging situation,” he said. “If lenders start to put large numbers of owners in default, number one, they don’t really have the capacity internally to handle all those defaults. Secondly, that is just going to devalue their underlying collateral, which is going to have a material ripple effect across their portfolio, which is something they certainly want to avoid.”

Most everyone, in other words, would be best off providing their counterparties as much flexibility as possible. Doing that, though, means managing a number of moving parts.

Already there are signs that this could get tricky. To take one example, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) that was passed into law last month allows for homeowners with a federally-backed mortgage to delay payments for at least 90 days. The law didn’t, however, address mortgage servicers, who are still on the hook for payments to investors even if they don’t receive the monthly payment. That has servicers warning of a cash crunch, with a group of industry organizations putting out a press release this weekend calling for the government to “provide a liquidity facility for single-family and multifamily servicers.”

“The government has set up a structure whereby it wants to make sure people can stay in their apartments,” said Mike Flood, senior vice president of commercial/multifamily policy at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “And if you’re a borrower, you can receive forbearance as long as you don’t evict those people. That’s great. But now you have to take care of the [servicers] for the whole system to work.”

Appel said that while the servicer landscape could be “a little bit opaque and slow-moving” for borrowers trying to navigate it, he expected that large servicers in the commercial real estate space would put in place “certain underlying guidelines … in terms of how to deal with loans that were in good standing that may no longer be in good standing due to a lack of revenue related to the crisis.”

“We think there will be some industry standard-type policies or positions that servicers take for their entire portfolios,” he said, adding that more bespoke solutions can be developed for individual assets that aren’t effectively addressed by such industry-standard approaches.

Kathleen Olin, managing director of industry initiatives at the CRE Finance Council suggested that standardized solutions would be difficult to implement for some types of investment products.

“With something like CMBS — given any combination of the borrower, the property, the loan structure, the servicing contract, who the servicing parties are, and who the investors are — when you take those different factors, you really have this infinite combination of circumstances where an across-the-board solution isn’t necessarily the right way to approach it,” she said.

Given these complexities, Olin said it was important that borrowers communicate potential issues to their services as soon as possible, a sentiment that was echoed by several other observers.

“We are advising our clients to anticipate problems and communicate that you are committed to the asset,” Appel said. “That you are expecting substantial rent shortfalls from these assets and that after paying baseline taxes and insurance on the building you are going to pay your debt service with any revenue that comes in and that, to the extent you are short, you would want that balance to enter into some sort of forbearance period until the asset is fully operational again.”

Flood said that the MBA has been setting up calls with organizations like the International Council of Shopping Centers and the American Hotel and Lodging Association which represent the borrower side of the equation.

“The idea is to get them talking so that when a borrower wants to talk to their servicer, they come with the best practices and information they need in order to have good discussions with their servicers,” he said.

At the moment, many landlords have limited visibility into what rent payments will look like in the coming months. Unemployment claims have skyrocketed, but expanded unemployment benefits could tide over some workers until the economy improves. Additionally, small business loans provided under the CARES Act are intended to help companies keep workers on payroll and cover expenses like rent and debt obligations.

Then there is the question of what sectors are better and worse positioned to ride out the storm.

“You look at the hotel and hospitality segment, and that has been hit really hard,” said Maturo. “And then retailers, I think you have to put them in a little bit of separate box because they may have deeper and longer-term issues they have to address.”

“But I think with residential, office, industrial, lenders generally feel that any disruption is going to be temporary, and I don’t think anybody wants to get all heated up over it yet until empirical evidence from the rents is gathered,” he added.

May 1 will be a key point for gathering such evidence, said Michael Lefkowitz, an attorney with Rosenberg & Estis. Debt service payments are paid in arrears, meaning April payments were made with March rents, reflecting tenant finances prior to the peak of the coronavirus crisis.

“Most of my clients had solid March collections,” Lefkowitz said. “But the issue is going to be April rents and whether or not businesses that have been told that they cannot open or those which are… operating remotely are going to be in a position cashflow-wise to pay their rent. It’s something we are all monitoring very closely.”

He said that thus far he had dealt with one property, a shopping center in Florida with a number of restaurant tenants, that had been unable to make its debt payment. In that case, the lender has agreed to “stand still on debt service payments,” Lefkowitz said, noting that the lender was a bank with which the borrower had a long term relationship.

“In that situation, they knew there was going to be an April 1 problem,” he said. “I think a lot of landlords still can’t say for sure. They know there is going to be some distress, they know there are going to be some issues, but you can’t know for sure exactly what those will be, unless [the property] is largely retail, largely restaurant, because those are the ones that have felt the most direct effect.”

Maturo said that April rents for RXR’s commercial tenants came in “with limited dilution,” adding that while rents for the month were not yet fully in, its large company tenants and most of its mid-sized companies had paid.

“I don’t think anybody is looking to press any buttons in terms of default notices or things of that nature,” he said. “Before there is a move, I think everybody wants to see what happens.”

About one-third of apartment renters, or 31 percent, in the country did not pay rent in April, a 12 percentage point increase from the previous month, according to a survey from the National Multifamily Housing Council released on April 8.

Schwartz said Slate Property had also seen solid rent payment of April rents, though he noted that his company’s portfolio has little exposure to hard-hit areas like the service industry.

But while the full fallout of the pandemic has yet to be felt, the industry remains worried that it is coming, he suggested. “If this doesn’t turn around soon-ish, people are concerned about May rent.”

Appel likewise indicated that things would probably get worse before they got better.

“The majority of our business has been focused on sourcing equity for transactions and placing credit for borrowers,” he said. “We think there is going to be a big shift in our business to advising people on achieving the most optimal type of forbearance.”