How Donald Trump Got His Start With the Grand Hyatt

By Aaron Short March 22, 2020 2:00 pm

reprints

By this time next year, a 40-plus year vessel of President Donald Trump’s insatiable ambitions will be no more.

Midtown’s Grand Hyatt Hotel, the refurbishment of which propelled Donald Trump into the clubby realm of Manhattan real estate mogul-dom four decades ago, will no longer abut Grand Central Terminal.

The building’s current owners, TF Cornerstone and MSD Partners, will demolish the stately 1,298-room hotel and replace it with a 2-million-square-foot office tower in a plan they announced in February 2019, as Commercial Observer reported.

The hotel is expected to remain open for the rest of this year — although it’s uncertain how many people are checking in, after the city’s hospitality industry abruptly cratered amid a global pandemic that shows no signs of letting up.

But eventually, the glass-and-steel facade that Trump retrofitted onto the hotel’s majestic bones in 1980 will come down. A much larger office and retail building containing a scaled-down Hyatt hotel will sprout in its place.

No one should get too sentimental about the loss of the Hyatt. After all, demolitions are part of a growing city and the Midtown East rezoning that passed three years ago paved the way for a new crop of office and residential space in the city’s densest business district.

And Donald Trump is no stranger to demolitions, razing the Bonwitt Teller building on Fifth Avenue to construct what would be the crown jewel of his family’s real estate empire and also serve as the campaign headquarters and home of the president-elect.

Yet a little bit of Trump’s past disappears with the erasure of the Hyatt. The story of how the Queens developer leveraged his family’s capital to make his first Manhattan deal is now political legend. Manhattan has moved on away— even if Trump hasn’t.

Donald Trump wanted to be a somebody — and to be a somebody you had to play in one of the most cutthroat markets in the world.

His father Fred Trump bought up property and built single-family homes in Queens during the Great Depression and garden apartments for families of veterans during World War II in Virginia and Pennsylvania. With the help of substantial federal loans, he developed post-war apartment complexes in Bensonhurst and Coney Island for middle and low-income families. (His methods for squeezing revenue out of his developments and pocketing loans drew the attention of state and federal housing investigators.)

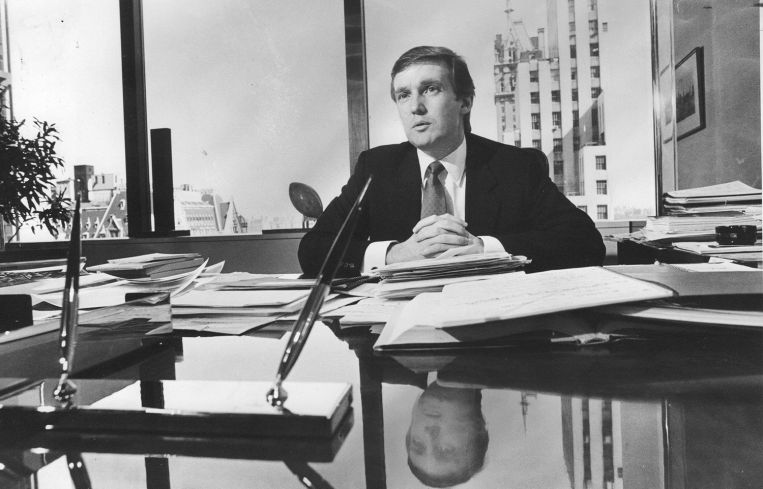

By the time Donald joined the Trump Management Company in 1968 the family had about 14,000 apartments in its portfolio across Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens. Three years later, the 25-year-old was named president of the firm by his father and he moved into an apartment on East 75th Street in Manhattan.

Both men visited apartments and toured construction sites around the city with thoughts of how to expand their empire. Fred mostly stayed in the outer boroughs but Donald had his eyes on the skyline.

“Donald is sort of unique,” said Andrew Stein, who was a Manhattan state assemblyman at the time. “The other guys, the Rudins and the other big families, were much more low-key, much quieter. And, with Donald, it was a showman from the get-go … He’s always been like that. He always loved the publicity and attention.”

He did not inherit those traits from his father, Stein believed.

“Fred was a very natty dresser, a very low-key guy in a lot of ways,” Stein said. “He did everything sort of quietly. He owned all these apartments in Brooklyn and Queens, and Donald wanted to break into the Manhattan market.”

Meanwhile tenants at the Trump properties started to fight back over years of racial discrimination and shoddy treatment. A series of complaints that the Trumps turned away black applicants looking to rent at their properties drew the attention of the Justice Department, which then sued Trump Management in 1973, according to the New York Times, putting Donald on the front page ignominiously.

The Trumps needed a lawyer and the man they hired would shape the Trump’s legacy for the next half century: Shortly after the lawsuit became public, Donald bumped into Roy Cohn at the members-only hot spot Le Club in the East 50s and asked for his advice. Cohn encouraged him to “go to hell and fight the thing in court and let them prove you discriminated,” Trump recounted.

It would be his most consequential hire until The Apprentice. They countersued the federal government for $100 million for defamation and held a press conference announcing the action. The suit would be tossed out after Trump settled with stipulations to halt future discrimination at his properties while he didn’t have to admit guilt.

With the nation’s most politically connected attorney on his payroll, Trump set his sights on Manhattan and charming the city’s political class.

“I had dinner with him first in 1974. That’s the first time I met him,” Stein said. “He was lobbying me about the rent laws. Roy Cohn called me and said, ‘I’d like you to meet Donald Trump.’ So, we had dinner and he lobbied me about the rent regulation and rent laws.”

Soon an opportunity in Midtown presented itself.

The Commodore Hotel opened in 1919 and quickly became known as one of the most luxurious hotels in the United States with an expansive lobby, low-slung ceilings, a waterfall, and one of the best locations in the city as the neighbor of a major railroad station.

But the 26-story hotel and its owner the Penn Central Transportation Company struggled in the 1970s, forcing its closure. The hotel lost $1.3 million in 1975, according to the Times, and would have lost $4.6 million in 1976 if it had stayed open. Its occupancy dropped from 46 percent in the first three months of 1975 to 36 percent the first three months of the following year, reports said at the time.

Trump had been hustling to look for a property in distress. With the hotel set to close and layoff thousands of workers, Trump approached Penn Central with a plan to refurbish the property for $77 to $100 million and bring in the Hyatt Hotels Corporation to run the new building.

Trump didn’t have the cash to buy the property and he certainly didn’t want to pay for it with his own money. But he had two advantages to make the deal work. His father Fred co-guaranteed a construction loan with Hyatt for $70 million to spur the project. Hyatt took a 50 percent stake in exchange for managing the hotel.

But Trump insisted he did not want to pay for the property himself. Instead he used his political connections, guided by the hidden hand of his cutthroat attorney, to lobby state and city officials for a tax subsidy that would be unprecedented in city history — a new program specifically designed to spur business investment when the city teetered toward bankruptcy.

Trump convinced then-Councilman Michael Bailkin to set up a 40-year tax abatement on the property, the longest ever granted by the city, allowing the state to own the land under the hotel and lease it for $1.

But he needed the support of Richard Ravitch, who Gov. Hugh Carey put in charge of the New York State Urban Development Corporation. Ravitch got a call from a fellow parent from his child’s school who asked whether he would be able to meet with a client of hers named Donald Trump.

“Trump came into my office and said that he purchased the Commodore Hotel, was converting it to a Hyatt, but couldn’t get the financing and needed a tax exemption,” Ravitch said. “I had the power to grant tax exemptions for economic development purposes. I did not think that a Hyatt Hotel on 42nd Street required tax forgiveness, and I said, ‘No.’ ”

Trump went around Ravitch and secured support for the plan from Carey, Mayor Abe Beame, and the agency’s board which ultimately approved it.

Trump got his $4 million-per-year tax break and spent $100 million to envelop the Commodore in glass. He was also shrewd enough to bring in contractors who knew what they were doing.

“Whether it was to his credit or to others, he had a lot of people working for him that were political,” said Barbara Res, a Trump Organization vice president who worked for a subcontractor on the hotel. “He was very brash and very inexperienced and he had us doing things that were not smart because he insisted on it. But Trump started a little bit to listen and he learned a little bit about the business.”

There was still the matter of a subway connection Trump promised to fund between the 42nd Street station and the east and west side of the hotel. Trump reneged on the promise, infuriating the city’s new mayor, Ed Koch.

By then, Ravitch had left the housing board to run the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Trump had Cohn call the MTA counsel to demand Ravitch build the connection between the 42nd Street subway and the Hyatt.

“I said, ‘There’s no way I’m using a penny of public money for that. I would be glad to do whatever we could to facilitate it, but I’m not spending any public money,’” Ravitch said. “The next morning, I got a call from Ed Koch, who I had a wonderful relationship with, and he said, ‘What did you do to Donald Trump? He called me up and told me to fire you.’ I said, ‘Ed, did you tell him you can’t fire me, you didn’t appoint me?’ and he laughed. We talked about Donald Trump until the last time Ed went in the hospital.”

The newly refurbished Grand Hyatt Hotel and the city’s provocative real estate magnate both arrived in 1980. Trump was firmly an up-and-comer when he finished the Hyatt.

“He made an incredible deal on the Hyatt. They went for many years without paying any taxes on it,” Res said. “It was double the budget but it didn’t matter because Hyatt made so much money that the rooms were triple what they thought they would get. But it was a big splash.”

A portion of the reporting originally appeared in “The Method to the Madness,” published in 2019 by St. Martin’s Press and co-authored by Aaron Short and Allen Salkin.