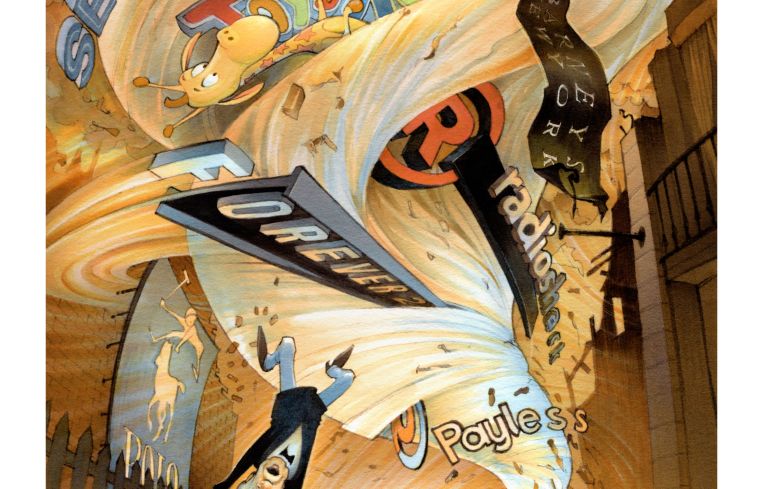

Retail’s Punishing Decade

Barneys bombed. Toys ‘R’ Us tanked. Forever 21 was not-so-forever.

By Nicholas Rizzi December 17, 2019 12:00 pm

reprints

If you wanted to sum up the story of retail in the 2010s, you could do worse than examine the case of Ralph Lauren.

When the luxe clothing retailer signed a lease for a 38,000-square-foot flagship at 711 Fifth Avenue back in 2013, the deal demonstrated the excitement and faith that all the parties involved had in the power of a high-powered brand on a high-trafficked corridor. The recession wasn’t completely in the rearview mirror, but the future was looking brighter. The deal won the Real Estate Board of New York’s Ingenious Deal of the Year award.

But by 2017, things had gone horribly wrong. Ralph Lauren decided to eat the cost of $68,500 in daily rent rather than stay open, as reported by the New York Post. It was lights out for the impressive flagship — with its charming coffee shop, working fireplaces and vintage fixtures — less than four years into its run.

And Ralph Lauren is one of the lucky ones; at least they haven’t declared bankruptcy.

No sector of real estate has had a rougher ride over the ups and downs of the decade’s roller coaster than retail. The 2010s kicked off with the industry reeling from the effects of the financial crisis, and e-commerce giants like Amazon grew dominant as people learned that they loved to shop from home. Many iconic, even decades-old retailers were forced to file for bankruptcy, and were then sold for scraps or shuttered completely.

“Retail brands and retailers are all in a downward spiral,” said retail consultant Kate Newlin. “It just is less and less defensible to say, ‘I think I’ll go shopping today.’ That behavior is going away.”

Some have dubbed this decade a “retail apocalypse” — others think that’s a bit melodramatic. But many veteran brokers have said this isn’t like any other downturn they’ve weathered in their careers.

“This does not feel like a cycle,” said Michael Hirschfeld, a vice chairman of national retail tenant services at JLL who’s been in the business for four decades. “This feels like a tectonic shift. This is not recovering.”

From 2015 to 2019, at least 81 major retailers filed for bankruptcy, according to a report from CB Insights. Among the casualties this decade were RadioShack, Gymboree, American Apparel, Payless Shoes and Toys “R” Us. And department stores have been particularly bruised.

Last year, Sears — once the largest retailer in the United States, and one of the most iconic — filed for bankruptcy with $11.34 billion in debt and announced plans to close more than 500 stores nationwide. Henri Bendel closed its iconic New York City flagship store in January after its parent company liquidated its assets. Macy’s announced plans to shutter more than a dozen stores nationwide. Lord & Taylor, one of the country’s oldest department stores, was sold to 7-year-old clothing rental startup Le Tote for $100 million in August, and that was after the retailer had already sold its 424 Fifth Avenue flagship to WeWork and Rhône Capital for $850 million.

The latest blow landed in November when Barneys New York was sold to Authentic Brands Group and B. Riley for $271 million, with plans to close the majority of its seven stores around the country and license Barneys’ name to competitor Saks Fifth Avenue, which Authentic Brands owns.

The loss of department stores also contributed to the record numbers of malls closing across the country, causing mall owners to scramble to add movie theaters and coworking spaces to lure customers back through the doors.

Kenneth Hochhauser, an executive vice president at Winick Realty Group, blamed the casualties not so much on a retail apocalypse but instead on what he coined a “choice apocalypse.” Consumers now have infinite options available — both off- and online — to purchase everyday items like jeans, and so they don’t need to rely on traditional stores.

“I can get things anywhere, anytime,” Hochhauser said. “So that dollar, instead of it being channeled to 10 retailers, literally, I could spend it on 100.”

The biggest shakeup this decade, experts said, was the rise in the proliferation of technology and e-commerce; from online-only brands like Casper offering door-to-door mattress delivery to mall owners using shoppers’ cellphones to track their habits. Now traditional brick-and-mortar retailers have focused on integrating their online presences throughout their companies, said Meghann Martindale, the global head of retail research for CBRE.

“It’s been online [and] e-commerce versus brick-and-mortar, offline retail, and they were competing and operated in two completely different silos from a business model standpoint,” Martindale said. “[Now] we’re seeing the real integration of those two coming together from a business model standpoint, a brand experience standpoint. Consumers are shopping interchangeably between the two.”

Retailers previously didn’t know how to allocate sales to specific store locations at the beginning of the decade — even if a customer visited the store and later bought the product online — but now have figured out ways to better track those numbers, said Robin Abrams, a vice chairman at Compass.

“There was mass hysteria and a huge disconnect,” she said. “Now I think there’s less concern and there are different creative ways retailers and developers get around it.”

And it hasn’t been all doom and gloom this decade. There were new batches of tenants filling space — including formerly online-only brands — and record-high rents. Massive new retail projects also finally crossed the finish line or started to open this decade; in the New York area, Related Companies’ seven-story Shops and Restaurants at Hudson Yards opened in March, the Empire Outlet mall on Staten Island opened in May and the long-delayed, 3.1-million-square-foot American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, N.J., opened its first sections in October.

But not everybody’s convinced these projects — which have been in the works for years — still make sense in today’s retail climate.

“I don’t imagine that this investment thesis is going to hold,” Newlin said. “I think reality outpaced Hudson Yards. It just feels sad.”

“I couldn’t imagine anybody actually buying anything there,” she added. “I never see anybody carrying shopping bags out of Hudson Yards.”

The struggles of the decade also created pockets of opportunities for retail brokers to negotiate better deals for tenants, especially right after the 2008 financial crisis when owners felt “the world has come to an end” and were more willing to work on leases, Hirschfeld said.

“I think lenders would say a low point was 2009, but 2009 was a springboard for us,” said Hirschfeld who, with Steve Ferris, founded brokerage Surge Retail, which was bought by JLL in 2013, leading to “seven pretty amazing years so far,” Hischfeld said.

Most brokers expected the worst coming into the decade, but were surprised by how fast Manhattan’s retail market got back on its feet.

“The marketplace in Manhattan rebounded, in my opinion, much more quickly than most anticipated,” said Andrew Mandell, a managing partner at Ripco Real Estate, “so much so that by 2014, retail rents had reached their all-time high.”

Average retail rents in Manhattan were $530 per square foot in the first quarter of 2010, according to CBRE. They reached their peak in the fourth quarter of 2014: more than $1,000 per square foot.

“You had these almost inexplicable deals that were being made,” said Mandell. “What happened from that point forward was you started to see these retail bankruptcies occurring. Reality set in and sometimes it’s a bit of a domino effect.”

Since then, Manhattan retail rents slid into their longest slump in 17 years, and in the third quarter of 2019 average asking rents in the borough were $756 per square foot, according to CBRE.

“What a lot of landlords didn’t realize, and retailers too, was that you can’t keep raising rents by 25 percent, 35 percent and 50 percent if sales were going up 2 percent or 3 percent,” said Lon Rubackin, a senior vice president at CBRE. “It’s not like the spigots turned on and retailers started doubling their business.”

Retailers weren’t the only ones that began to struggle; landlords started to feel the pain too. For example, Thor Equities’ $37 million mortgage at 115 Mercer Street — which it bought in 2013 — was sent to special services in April, partly due to trouble with its retail tenants Roland Mouret, Kooples, and Derek Lam, the Wall Street Journal reported.

The landlord also had its loan at 545 Madison Avenue sent to special servicing in May and defaulted on its $17 million loans on its retail property at 1006 Madison Avenue that same month, The Real Deal reported. Thor has subsequently started pulling out of the city’s retail market to focus instead on industrial, as Commercial Observer previously reported. A spokeswoman for Thor declined to comment.

“When you’re at a peak and you’re an owner, you’re in a very difficult position,” Mandell said. “If you have a space that’s available, one of the issues you’re hearing is that the market is softening, but you’re still holding on and you just witnessed the historical leases that have been signed at this time. When it settled in, I think that the leasing process took longer.”

The astronomical rents of 2014 and 2015 also led to storefronts staying vacant longer and contributed to another new trend: temporary pop-up stores.

“It was spawned by this environment where owners were waiting and didn’t want to lease space long-term,” Mandell said. “Now it became an avenue if you wanted to try an area or expansion on a very short-term basis.”

Landlords and brokers initially turned their noses up at the pop-up phenomenon, where stores can stay open for as little as one day, but more and more those became the only deals that could get done.

“You get the occasional broker [saying], ‘I don’t do pop-ups,’ ” Abrams said. “I’m like, ‘Really? What have you done for the past two years?’ Because nobody was doing real deals. It just wasn’t happening.”

The general reluctance on behalf of many landlords to take seriously the pending warning signs was not without reason.

“Conversations I remember having — particularly in the U.K. back in 2015, 2016 — I was sitting with mall owners saying, ‘If I were you, I’d be really concerned for these reasons,’ ” said Ross Bailey, CEO and founder of Appear Here, which books temporary space for retailers. “Now, if you look at some of the biggest REITs in the U.K., or mall businesses, if you look at their market cap in 2015, 2016, they had the best year they ever had. So, you’ve got some young schmuck sitting in the meeting telling you the internet is going to change all this stuff … they’re like, our share price is [going through the roof], we’re good. We’re having the best year ever.”

The prevalence of pop-ups helped previously online-only brands establishing a real-world presence. A growing number of them then opened long-term brick-and-mortar outposts, including Casper, shirt company Untuckit, and even Amazon.

“The rise in digitally native brands going to bricks and mortar is huge,” CBRE’s Martindale said. “I think we will continue to see that … From a brand awareness and a consumer acquisition component it’s been proven — because we’re seeing hundreds of new digitally native brand stores opening — that they see the value in having that brick-and-mortar store.”

Pop-ups also got landlords more comfortable with flexibility in leases. While a 10-year lease was common at the start of this decade, now five years can be considered long term and many street-level retail space owners are signing 10-year leases with the option to leave in five years, something that was only previously available in malls, Hirschfeld said.

“It’s a lot more creative negotiating,” he said.

A newer phenomenon is the rise of department stores like Neighborhood Goods, Bulletin and Showfields. The stores bring together several digitally native brands under one roof, allowing them to dip their toes in offline selling without the commitment to a traditional lease.

And, at traditional department stores, which have seen closures, other types of tenants have started appearing. Gyms, athleisure brands, restaurants, virtual-reality arcades and movie theaters have all been taking more retail space this past decade.

“We’re seeing the shift with entertainment where technology is giving them the ability to be a lot more nimble and go into more unique spaces and more urban environments in smaller footprints,” Martindale said.

However, these new tenants have opened fewer locations and signed for smaller square footage in the past decade, Hirschfeld said.

“You have parallel phenomenons of shrinking store count [and] shrinking store size,” he said. “Every time a tenant does a deal to replace something, very often they’re taking less space than they had. So a deal gets done, but more space comes on the market.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)