Lou Naidorf’s Legendary Career From Slapsie Maxie’s to the Capitol Records Building

By Michael Aushenker October 18, 2019 5:52 pm

reprints

Contrary to popular opinion, the Capitol Records building was not designed to resemble a stack of records.

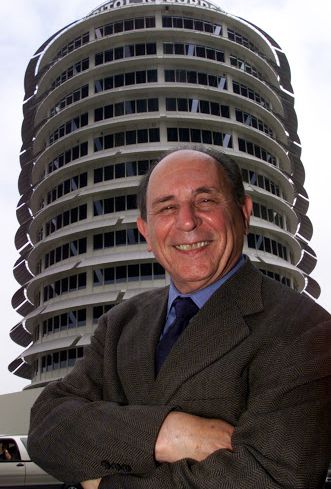

That comes straight from Lou Naidorf, the longtime architect at the legendary Welton Becket and Associates firm who designed the 13-story building at 1750 Vine Street that has served as corporate headquarters of one of the music industry’s great labels while still in his early 20s.

For four decades — from 1950 through 1990 — Naidorf worked for the late Welton Becket, who had a hand in such iconic mid-century masterpieces as Santa Monica Civic Auditorium and The Theme Building, that flying saucer mothership centerpiece at Los Angeles International Airport which, until recent years, housed Encounter restaurant.

However, the most iconic design to emerge from Becket’s famously Googie-esque architecture firm was arguably Naidorf’s Capitol Records building, which opened in April 1956.

Becket formed Welton Becket and Associates, which he grew into a worldwide firm before his 1969 death. The design studio has since been folded into Ellerbe Associates and was eventually acquired by AECOM. Today, the firm is known as Ellerbe Becket, an AECOM Company.

In 1990, after leaving the Becket firm, Naidorf became the founding Dean of Architecture at Woodbury University in Burbank; a role he served for 10 years.

Today, Naidorf, who turned 91 on Aug. 15, lives in Santa Rosa, Calif., having relocated to Northern California to live closer to daughter Victoria Naidorf, a prominent real estate attorney at Coldwell Banker who lives in Walnut Creek.

When Commercial Observer caught up with Naidorf for a conversation by phone, 10 days after the passing of his wife of 16 years, Sandy Chronos Naidorf, who had passed away after a long-debilitating disease.

“Thankfully, she ended in the most peaceful way,” Naidorf said. “I kissed her five minutes before she passed.”

Sandy was Naidorf’s fourth wife. Naidorf had five children and today has 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren, “all of whom I like,” he said.

Commercial Observer: After 40 years working for Welton Becket and Associates, you became Dean of Architecture at Woodbury University in 1990. What was Woodbury like when you arrived?

Lou Naidorf: Woodbury was in bad condition, which I was naïve about, but the extra money came in handy. It was really at the edge financially. They brought in a new president, Paul Sago, and he’d come from Azusa Pacific University…he took over the place when it was literally on the brink of bankruptcy. He brought in a couple of partners and tried to transformed the place.

What did you do upon arriving at Woodbury?

I let the entire adjunct faculty go and hired young teachers. It was turning people loose to do things. And for the [predominantly Latino and low-income background] kids, it was important for them to get out of the victim mode.

We all have to work our asses off and we did. It was an incredibly energizing time. I wanted them to know that it was in their hands. I felt it was critical to take away fear, give them emotional support and show them that it was their lives. I still get calls from the students, they’re now middle aged.

How did you get the program going?

I was almost 62 at the time. I had come out of an office. I had taught at all of the other schools in the area, but I was completely unaware of the educational system. And now I’m in this dump. And it was freeing. Everyone said you must have been dismayed. I feel like I was let loose.

The program was so bad, we weren’t even listed. My goal was to have the finest program in the country. At our first meeting with the kids, I told them that the school was dreadful.

When I got there, they would’ve taken in anybody who would breathe…It was a grab bag of kids. [But] I could see in the work there are kids that are high school dropouts who are doing better than students with PhDs. I believe that if you presented kids with challenging projects, be absolutely candid and had faith, that they could do it, they would do remarkably well.

How did you leave it 10 years later?

It took just over three years to become accredited. The school went from being a pariah to a model school and it’s been improving ever since.

What was it like working there?

It was like at the Becket office. I thought tight budgets were fun to work with. It’s like playing on a wet day with a string missing from your racket — but it was a wonderful fresh feeling to have a president as a partner in crime who had been miffed that he had to be at this crap-ass school. It was a change to build out of dirt, mud and belief. The greatest thing was to watch the flowering careers of people who wouldn’t even let them into the door.

Let’s go back further in time: How did you arrive in Los Angeles, working for Welton Becket?

I didn’t know anything. I was 19-and-a-half and I was married for two years at that point. I skipped [University of California] Berkeley. I had no money and I had to get a job. I graduated the first in my class and skipped a year. The new dean of architecture, William Wurster, wrote me a letter of recommendation to five firms in Los Angeles. I told him I had to get back to L.A., where my wife was, and that’s where the work was, actually.

They had done a building with sunshades on it, the Prudential Financial Insurance Building on Wilshire Blvd., west of the La Brea Tar Pits. Becket was very near the Prudential building on the Miracle Mile. The Becket office had moved out there. He had a habit of getting a major client and then moving near where the project was going to be.

How big was the Becket firm when you started there?

He had 90 on his staff. It was 1950. What I didn’t realize at the time he had middle-aged staff in their forties all of these architects hadn’t worked for the better part of 20 years because of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Although architecture died [in this period] the film industry burgeoned. People needed to get their minds off of the Depression they needed set designers — particularly architects trained in historic work. They could design Nero’s palace, they could do Gothic, they could do anything. They had very little experience, they were unlicensed. They came into the firm four or five years before me and they had very little experience in architecture except working on sets.

On a Tuesday, I drove down to L.A. in a 1934 Ford. The naiveté of a 21-year-old, I go in there into the conference room and there’s Welton Becket along with his director of design, his director of electric engineering, the five top people in the firm — all interviewing a kid coming in for a junior drafting position. They offered me a job for $1.75 an hour. In San Francisco, they were paying 80 or 90 cents an hour.

What projects were they tackling when you arrived?

They were working on UCLA Medical Center. It was well-advanced. My first assignment at the office was to design the little tubing support in the cafeteria that your tray rides along. This was a massive job. You have to understand, I love what I did, and I loved every little fucking part of it, so I don’t care. The next job was a bar run by “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom, ex-boxer. He bought what used to be a Van De Kamp’s Bakery and took it over and turned it into a restaurant. This was a small job but it was right next door so I took on that. I designed the sign: “Please wait to be seated.”

How was Becket supportive of his employees?

I was the lone atheist Jew from Berkeley. I was the lone Democrat, everyone else were nice blond Republicans. Becket himself, his family descended from Sir Thomas Becket.

He was a classmate of Wurdeman. he was a physical guy he went hiking in mountains East of Washington. Wurdeman had a heart attack, Becket carried him out. Saved his life. He then went into partnership with Wurdeman knowing that Wurdeman was living on borrowed time. They were in business for about 20 years. He had built a partnership desk for Wurdeman. He died one-and-a-half years before I got there. Nobody sat at that desk.

Another story is more direct. One day, I’m beavering away. I look up in my cubicle. The office is dead. Everyone had gone to lunch; the whole place is empty. I hear a voice in the back and it’s Welton Becket. I can hear his voice talking to [a client] named Charlie. Welt says, “Charlie, let me give you a tour of the offices. It’s empty now, everyone will be back in 15 minutes.” He tells Charlie, “Charlie, I’ve got the perfect architect for you: Philip Kimmelman.” Charlie replies, “Do you have any other project architect?” Welt says, “Philip would be perfect for the job.” I’m quickly picking up on what’s bothering Charlie. Charlie tells Becket, “I would prefer the project manager doesn’t have a name like Kimmelman.” I hear Becket say, “I understand. Let’s walk back to my office, Charlie. Let me show you to the elevator, I think you’ll prefer a firm that doesn’t have a name like Becket.”

Wow, he really came to the defense of his Jewish employee.

[At the same time,] Becket was bigoted, paternalistic and paid no more than he had to. It was the way of the time. And by the way, he put up with an enormous amount of crap from me. He was a member of L.A. Country Club. The guy came in and talked about the situation in Cuba. I had designed the Havana Hilton. He once said, “Anybody in Cuba with any brains in them has some white in them.” I said to Welt, “How can you say something so dumb?” He looked at me and said, “Why are you so hard on me, Lou?” I said, “Because you just sit there with the white bread at the country club. You’re wrong, you’re just fucking wrong.” Anybody else would’ve fired me. He had an innate loyalty to his people.At what point did you get the Capitol Records assignment?

I got Capitol Records very early. When I was 24, [Becket] called me into his office, which was unusual, closed the door and said, “We have a confidential project I’d like you to design it.” I asked who the client was. He said, “I can’t tell you, it’s confidential. No one in the office is to know anything about the project, you’re not to discuss it with no one. It’s a block away from Hollywood Boulevard, a small building and they want small floors.” It was under the 13-foot story and 150-foot height limit. That was not an earthquake-related requirement, it was an urban designer requirement. They wanted a tower that was 100,000 square feet with floors less than 7,000 square feet per floor, 13 floors and, surprisingly, the second requirement was a very unusual one. Usually, there was a bottom floor, a large lobby and retail space, but this was to have a very small lobby and to sit on top of a high windowless box and a little entrance lobby.

What was your first impression?

Funny thoughts are going through my head. It was like “The Twilight Zone.” They wanted it as equally sized as possible. Small, very cheap. It was the cheapest office building ever built. It was really bare-bones.

I had just finished a master thesis; an office building around the Presidio in San Francisco. And I was asking myself, “What goes on in an office building? Business! What about a government building? They’re bureaucrats, they run stuff.” I’m trying to understand how the building works. At a factory, they make cars. I’m thinking about it, there’s one super-computer in the country, ENIAC, making gunnery calculations for the Navy. I want to do the building for 50 years from now. I set the building for the year 2000. How will the buildings differ? An architect reacts to changes. I saw a film that had an acre of people, all sitting at rows and rows of desks with adding machines. You know this computer is going to take over. Fifty years from now, they won’t have all these people, they’ll be replaced by computers. I did this mental leap. At the same time, I’m doing research on structures for the Moon. I’m quickly arriving at these conclusions. What comes into this building is raw information.

There were no corner offices, this guy wants no corner offices, they were all the same. So, I design the building, I put sunshades on it, a touch of color, play of light and shadow on it.

It’s a misnomer that people think it’s a stack of records?

Becket said the client is coming in next week, finish your model. A week or so later the client comes in I had some drawings this guy walks into the office, short guy in a navy suit white shirt very stern looking guy and he looked at the building and he said, goddamn it what was that? He was livid. He said to Becket, “I told him not to tell him anything.” [In walked Glenn Wallichs, he’s the head of the Capitol Records.] When he saw my design, he thought they had violated his confidentially. He said, “Goddamn it, people will think it’s a cheap stunt like Clyde would do.” His brother Clyde Wallichs — a slick, Cal Worthington type — owned merchandising arm of Capitol Records. Clyde ran Wallichs Music City [record store] and his owner brother Glenn was this stern conservative businessman who didn’t want to be associated with his brother.

I found out later that one of the reasons for confidentially was that Glenn didn’t have the land secured for the building. He was starting the preliminary association with [British record label] EMI for some kind of merger. He didn’t want them to know he was putting all of his capital – no pun intended – into this office building.

He was out to put a financing package together to the insurance company and get major backing. Becket calms him down. I didn’t tell him a word. This was a very specific building. Well ,I don’t want that I want a regular building. Becket said, “Come back in a couple of weeks and I’ll have something for it.”

So what happened next?

Now gets word out at the office that this design I’m working on looks like stack of pancakes and I’m the butt of all kinds of jokes. So, I put it aside and I put together a regular boxy building. And Glenn comes back and he likes it. I said, “Listen, take both [versions] in to the insurance company. The round building is more efficient but get a second opinion. So he takes both models to the insurance company. Two weeks later, I see him and I asked, “How did it go?” The insurance guy had told him, “Glenn, you’re going to have to occupy half the building and lease the other half. You’re not on Hollywood Boulevard. Do the round building, it’s damn good for leasing. So, bless some anonymous guy in the insurance company.

How long did it take to go up?

About 18 months. It was a very simple cheap, concrete building. It was completed at the end of 1955. They had the dedication in the spring of 1956.

The sunshades were metal with enameled surface. What was the ground floor this mystery? The recording studios. They had echo chambers that extended out under the parking lot in the back and panels they could rotate or move to have greater or less absorption.

[Capitol Records] had the Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Jack Mercer, Nat King Cole. Les Paul was involved in the design. We had him as an acoustic consultant.People probably assumed that it was intended to be a metaphorical building like the Brown Derby or Tail of the Pup. Did you spend a great part of your career correcting people?

Yes, but I gave up [because so many writers had gotten it wrong]. Greyhound Tours — of all people — called to ask if it was a stack of records. The only ones who were scholars of this were Greyhound Tours. In a way, it doesn’t matter because I designed the building to be a happy building.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly said that Naidorf lived in assisted living. He does not.