How an Iconic New York City Eatery Opens a Second Outpost After Nearly a Decade

After years of only one location, spots like Russ & Daughter and Katz's have opened new locations. Many of them in food halls.

By Nicholas Rizzi July 16, 2019 10:00 am

reprints

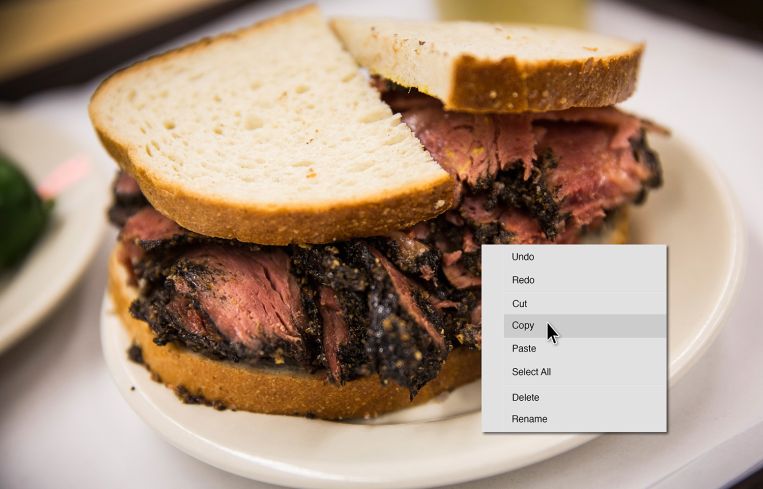

Katz’s Delicatessen has been open at 205 East Houston Street in the Lower East since 1888, serving up famous giant pastrami sandwiches and being immortalized in films like “When Harry Met Sally.”

And for nearly 130 years, the only way to taste the same sandwich Meg Ryan seriously enjoyed at Katz’s was to wait on their punishing line—which can sometimes snake out the door—and figure out the ticket ordering system. (A lost ticket is a $50 fine.) That is, until 2017, when the eatery opened up its second location ever, dubbed A Taste of Katz’s, at the DeKalb Market Hall in Downtown Brooklyn.

“We have a lot of regulars right over the bridge in that area,” said Jake Dell, the owner of Katz’s who started running operations in 2009. “It was just sort of a natural extension to be able to say, ‘Let’s bring the food just a little bit closer to you.’ ”

Katz’s is one of a growing number of iconic New York City institutions that have started to expand to new locations in recent years, many by opening stalls in food halls.

These include the 120-year-old Downtown Brooklyn Middle Eastern market Sahadi’s Industry City outpost, famed Staten Island pizzerias Denino’s and Joe & Pat’s (one of the only reasons some New Yorkers ever took the ferry) slinging pies out of Manhattan storefronts and the East Village’s famed Ukrainian eatery Veselka gearing up to open a stand in The Market Line food hall in the Essex Crossing development next month.

“I’ve been aware for several years of the growing trend of food halls opening up around Manhattan and I had a pretty strong feeling that the more popular aspects of our menu would fit well in that venue,” said Tom Brichard, who has owned 65-year-old Veselka for the past 50 years. “We became aware of Essex Crossing and it’s in a traditional immigrant neighborhood, it’s not too far from us and there were other similar establishments. For those reasons we were really attracted and decided to go ahead and open.”

Smoked fish purveyors Russ & Daughters has been especially prolific, after just 100 years. It only had one shop, at 179 East Houston Street, and it was strictly a shopping destination, not a restaurant. But in 2014—on its 100th anniversary—the fourth generation of owners opened up a sit-down eatery Russ & Daughters Cafe at 127 Orchard Street.

“We decided that we should offer our customers a place to sit down and eat Russ & Daughters,” said Josh Russ Tupper, who co-owns Russ & Daughters with his cousin, Niki Russ Federman. “After a lot of deliberation, we determined the Lower East Side to expand our presence to support the neighborhood and to really solidify who we are and where we came from.”

Russ & Daughters was wildly successful right out of the gate, garnering rave reviews and hour-long waits for its kippers and lox.

The duo kept going and opened another restaurant in the Jewish Museum in 2016 and then a commercial kitchen with a retail storefront inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard in February. In all of them, Tupper said they worked hard to maintain the same principles his family developed in the original shop—serving “simple, delicious food”—but the plans weren’t always greeted warmly by regulars.

“Russ & Daughters has customers that have been shopping with us for 80 years and a lot of them have strong opinions about what we do and how we do it,” he said. “We got a lot of customers that said, ‘What are you doing? Why would you do that? Don’t screw up this store we love so much!’ ”

“All of them visited the restaurant and said, ‘You did it perfectly, it’s amazing,’ ” he added. “It was great validation from people that were skeptical, to say the least.”

Dell also had to deal with people figuring out if the new Katz’s sandwiches lived up to the legacy of its Lower East Side ancestor, even though the pastrami is driven across the bridge from the original location every morning.

“There’s still an ongoing comparison, that’s sort of inevitable,” Dell said. “Some people swear they prefer one or the other. That’s O.K. with me as long as they’re happy.”

But while figuring out how to send out pounds of pastrami 10 minutes away from Manhattan to Brooklyn was relatively simple since Katz’s has been in the catering business for years, it would be nearly impossible trying to recreate the Katz’s experience elsewhere, Dell said.

“You can’t recreate nostalgia,” he said. “Some of that is really just one-of-a-kind. It can’t be bottled up, but the food can.”

For the design of A Taste of Katz’s, Dell instead focused on paying “homage” to the original deli. It has neon signs like the East Houston Street spot, even installing a vertical Katz’s sign on the stand similar to the one that’s stood outside the Manhattan spot for years.

Instead of lining up the Brooklyn Katz’s with photos of celebrities who ate at the eatery, like the original location, Dell instead went with shots that showed off the history of Katz’s throughout the years.

“We put just sort of nostalgic pictures of moments of Katz’s in the same style [since] obviously we don’t have the same celebrities,” he said. “Pictures of things that make Katz’s special.”

Tupper also knew there’d be no way to try to remake the Russ & Daughters storefront anywhere else but decided to add elements from it—like the lit boxes of products attached to the walls—to give it a similar feel.

“We never want to recreate,” he said. “We introduced elements of the store but didn’t try to make it look, like, 100 years old or exactly replicate the store, which we think couldn’t be done. The experience, we hope, is similar. You get to interact with your server and bartender the way people interact at the store with clerks.”

When coming up with the design of the Jewish Museum and Navy Yard outposts, Tupper said they had to basically start from scratch each time and make all new decisions.

“I don’t think that we ever will create a model or a visual that we can just replicate,” he said. “Just because it feels very corporate and franchisee and [that’s] not really what we’re all about.”

Part of the reason New York City icons like Russ & Daughters and Katz’s have expanded in recent years is due to the new breed of owners that have taken the reins of the family business. Tupper and Federman took over in 2010 and immediately had expansion on the mind. Joe & Pat’s, which has been serving up thin-crust pizza in Castleton Corners, Staten Island, since 1960, only opened at 168 First Avenue last year at the behest of the 26-year-old Casey Pappalardo when he joined his father and uncles in running the shop, AM New York reported.

Another factor has been the remarkable rise of food halls around the city and the country, with many like Katz’s, Veselka, Russ & Daughters, Sahadi’s and Di Fara Pizza using that as the platform to unveil act two. In 2016, there were about 120 food halls nationwide, but that number has grown to about 275 in 2018, according to a Cushman & Wakefield report published in May. C&W expects the number to climb to about 450 by the end of 2020. (And, despite the rapid growth of food halls, demand has matched it. In the past four years, less than 10 major ones shuttered, the report found.)

Food halls give eateries like Veselka and Katz’s a lower risk (and less stressed) venue to open a new location. They don’t have to deal with securing a large, expensive retail space to accommodate the restaurant or deal with a lot of the back-end work, like cleaning bathrooms.

“When you have a business that is iconic, it’s a huge operation, typically the owner is onsite every day,” said Rohan Mehra, a principal of Essex Crossing co-developer the Prusik Group, who handles retail leasing for the project. “As many things as possible to make [the owner’s] lives easier, you can increase the chances of taking them on board.”

Previously, if these eateries wanted to open a new location they would have to go out and raise money, enlist a broker to find a space and then hire a team of employees that could range from 50 to 75 people, said Trip Schneck, an executive managing director of specialty food and beverage, entertainment and hospitality at C&W. (Many icons chose instead to simply sell their food in supermarkets like Junior’s Cheesecake and Rao’s.)

“That’s a very difficult thing to do,” Schneck said. “It’s difficult to raise money for restaurants, it’s difficult to find attractive rent deals in certain locations like New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago or Miami. And it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find these talented workers and deal with rising wage costs.”

Schneck estimated a restaurant owner would now need to raise between $1 million to $3 million to open a spot in the city, which also includes buildout for the space that could cost $200 to $700 per square foot.

In a food hall, the buildout is already handled by the developer and an eatery only needs about four to five workers, so the money needed is only between $10,000 to $100,000, Schneck said. Plus, a food hall stall can get away with a much smaller menu.

Veselka’s Brichard said he has been “very, very conservative” about any expansions since taking over the business from his former father-in-law, despite countless offers throughout the years, but the ease of cooking pierogies at its original spot and sending them nearby to Essex Crossing made sense.

“We can prepare perogies ahead of time, refrigerate them and cook them really quickly,” he said. “We kind of see it as another way to remind people that Veselka’s still in the Lower East Side.”

Food halls can also have more flexibility in the structure of deals for eateries, Schneck said. Many of them work on license agreements—with the stall sharing 25 to 30 percent of profits with food hall owners—and they only need to commit to 12 to 18 months in that spot.

“I do think from a risk-reward standpoint, it’s a much safer bet than starting a restaurant in today’s climate,” he said.

At Essex Crossing, Mehra only requires six months notice if a brand decides it needs to close, making it less likely a new outpost can tank an icon.

“If something goes wrong with Tom [Brichard], personally I don’t need to ruin his business,” he said. “They see that’s my vote of confidence. It just helps them out tremendously.”

And it makes sense for Mehra to be especially flexible with places like Veselka because a spot like that can give a food hall a more neighborhood-y feel, get people in the door and even attract other eateries to sign deals. He even turned down offers from major chefs to favor smaller, community spots.

“Once you have Veselka, all of the other quality people start to see the vision that you’ve been telling them,” he said.

Aside from Veselka, Mehra also signed deals in The Market Line for second locations from Gowanus, Brooklyn, grocer S.E.A. Market and a family-run Lower East Side fishmonger, which will call its spot Essex Pearl.

Even if it’s less risky to open in a food hall, it isn’t all smooth sailing. Owners reported having to iron out a lot of kinks in the first few weeks, but they have one major advantage over new restaurateurs when opening a new spot: decades of passed down business advice.

Dell had issues getting the timing for deliveries and cooking right during A Taste of Katz’s debut, along with a piece of software for taking orders that failed early on, but he had an old saying his grandpa always told him to get by.

“Make sure the products good, and the rest will fall into place,” he said. “Make sure that pastrami is the best thing you’re going to have. That the matzo ball soup is maybe the second-best you ever had. That’s the most important thing.”

“Everything I’ve done has been about maintaining every single tradition here,” he added.