The Unforeseen Consequences of Prop 209 on African American Architects

By Alison Stateman May 13, 2019 3:47 pm

reprints

Amid Los Angeles’ real estate boom, care to guess how many of the major projects underway have an African American-led architecture firm behind them?

If you said none, you’d be correct.

Why, especially in one of the most demographically diverse states, is that the case? According to minority-led firms, particularly architecture firms led by African Americans, the main driver is Proposition 209, a ballot measure passed by the California electorate back in 1996. The measure, also known as the California Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI), amended the state’s constitution, adding a provision prohibiting discriminating against or granting preferential treatment to “any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education or public contracting.”

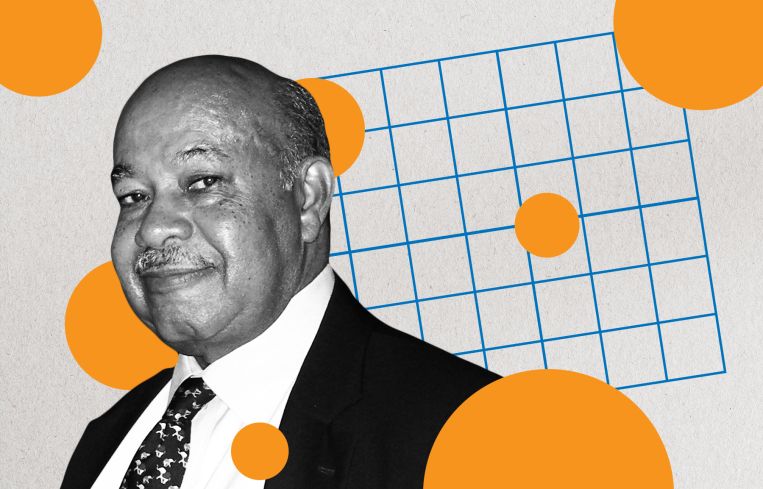

“If you look, almost 30 years later, black architecture firms have virtually disappeared and there are no major contracts that are being executed by black architects. None,” Roland Wiley, founder and principal of RAW International and a licensed architect, told Commercial Observer. “And I’m not speaking in hyperbole. I’m saying zero.”

Though the measure began within the state’s sprawling public university system as an effort to combat what some viewed as “reverse discrimination” against white and Asian applicants, its impact on the racial composition for architecture and construction work—even according to its main proponent—is the most notable. And not in a good way.

“The area that is most consequential is public contracting because in terms of employment you can go into just about any agency in California and you can see what we loosely describe as diversity,” said Ward Connerly (himself African American), who championed Prop 209. “The more select colleges have suffered a drop in black enrollment to some extent but the effect on higher education is not as significant as many would think at first blush. But in the area of public contracting, there was an increasing pattern of black people going into contracting on the basis of set asides and arrangements between prime contractors and the minority business enterprises and women business enterprises and that pipeline was sort of nipped in the bud from 209.”

Connerly, cofounder of the American Civil Rights Institute, a nonprofit whose mission is “to educate the American public, press and elected officials about the problems with racial and gender preferences in federal, state and local government programs,” still firmly stands behind the measure.

“We went from being a nation that was on the path to some very bad results to one that was really living out the meaning of the creed of this nation, which is that everyone is entitled to equal treatment under the law,” he said.

Connerly spearheaded the effort to ban affirmative action within the state university system while he served on the California’s board of regents, before helping put Proposition 209 on the ballot in 1996. He went on to champion and successfully pass initiatives modeled after Proposition 209 in Michigan, Nebraska, Arizona and Washington state.

“I think that [the loss of African Americans in public contracting] is probably the only serious consequence that I would regard as negative upon certain populations,” Connerly told Commercial Observer, “because they haven’t been able to make the adjustment to a quote ‘color blind’ procurement process.”

The historical lack of private investment in a lot of minority communities made public projects that much more important for black architects.

“Architecture in particular is a very specific industry where you need someone to, quite literally, pay for a building,” said Lance Collins, AIA, a director at Partner Energy and President of the Southern California chapter of the National Organization of Minority Architects. “There has never been a critical mass of real estate developers and banks and other institutions to invest in the private side in minority communities, which is the foundational piece.”

A lot of prominent African American architecture firms in the 1970s through the 1990s made their names from major public contracts, Collins told CO. These include Edward C. Barker, Harold L. Williams and Jack W. Haywood and Vincent Proby, who designed the California African American Museum in Exposition Park.

“Prior to ’96, there was the understanding that there were historical disadvantages that were placed on [these] firms. There were mechanisms that were trying to improve upon that and Proposition 209 just erased one of the biggest tools on the market,” Collins said.

Pre-Prop 209, smaller firms of all types, not just minority-led firms, were given a chance to be part of large public agency work to get the experience and qualifications needed to remain competitive.

“There was a political will to help minority firms, in particular get their experience level up so they could compete with larger Fortune 500 companies and larger construction groups,” Collins said.

Wiley concurred. “In our profession, it’s all about perception. With Mayor [Tom] Bradley [in the 1980s], the perception was if you were doing something in the City of Los Angeles, particularly downtown, he was going to want to see a black architect working on it,” he said.

Therefore, large private developers would reach out to black architectural firms to form joint ventures and bring them in on large-scale projects, something Wiley witnessed in his previous role as an associate at Gruen Associates from 1979 to 1984.

“There were three different black architectural firms that had staff in our [Gruen Associates] office that were part of the team, working on California Plaza. We also worked on MOCA [The Museum of Contemporary Art] on Grand Avenue. And that helped build their businesses and it helped open doors of opportunity,” he said.

“When Proposition 209 came about, it basically outlawed that kind of preferential treatment and the new elected officials, their hands were tied. It could not be race-based,” he said. “It took the professional world a little while to recover.”

As the professional world grappled with the new reality, public agencies and educational institutions had to come up with mechanisms to provide opportunities for historically disadvantaged groups.

In a post-Proposition 209 world, the county has been trying to identify and support small businesses and social enterprises, without singling out black-led firms.

In its 2016-2012 County of Los Angeles Strategic Plan, for instance, the county outlined a certification program for social enterprises, small business, disabled veteran-owned business and social enterprise utilization plan to achieve county-wide procurement goals of 25 percent for certified local small business enterprises and 3 percent for disabled veteran business enterprises.

The city’s Metro agency meanwhile, implemented a small business enterprise program which set an initial goal of awarding 15 percent of locally funded projects to small businesses, according to Tashai Smith, interim executive director for the program and deputy executive officer for diversity and economic opportunity at Metro.

That goal was increased to 30 percent since the mid-2000s she said. The agency has also established a small business prime program in 2014 in which specific contracts are set aside for small businesses to compete and grow as prime contractors for Metro. Contracts range in size from $3,000 to $3 million, Smith said. To date, the agency has awarded more than $110 million to small business firms within the prime program.

“Frank Gehry wasn’t a genius overnight,” said Wiley, who is the architect with Parsons Brinkeroff for the design of the Westside Subway Extension project among other Metro-related projects. “He’s got a whole slew of regular looking buildings before he got to where he is,” said Wiley. “We get maybe one building every 10 years and that’s no practice. We are in an environment that is inhibiting the rise and development of architects of color and I just think that’s tragic, not just speaking for my own firm, but speaking for the profession in general.”

But as long as Proposition 209 stands, it will impede many of the efforts to make L.A. more diverse in terms of public contracting. In 2014, black and Latino lawmakers tried to repeal the measure. After the measure to lift the ban quietly won state Senate approval, Asian American activists, largely concerned with how it might negatively impact their children’s opportunity to attend the state’s elite universities, caught wind of it and actively campaigned on social media networks and in direct outreach to elected officials to have it squashed, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“I just don’t see our society feels that anything is lost by excluding architects of color from this architectural conversation,” Wiley said. “Personally, in this polarized world we live in now, I don’t think it would get much traction. People are even more polarized now than when Proposition 209 came out so this is just the period of time we are living in.”

However, the tide, may be turning. A measure in Washington state modeled after Proposition 209, known as Initiative 200, for which Connerly successfully campaigned in 1998, was repealed by legislators in the state late last month, as The Hill reported. Whether it will stand or more likely be challenged in the future by groups negatively impacted by its banishment remains to be seen.