Woodstock Generation Changes the World of Senior Living

By Rebekah Sager February 28, 2019 5:28 am

reprints

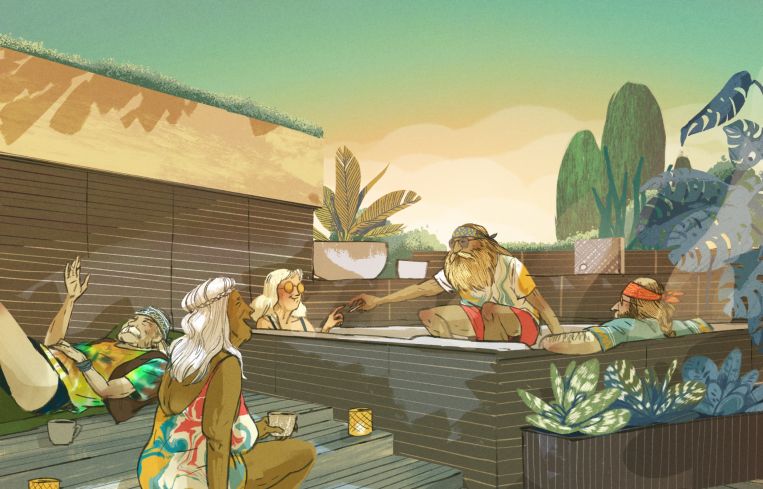

As the silver tsunami of baby boomers rushes in at record speed toward retirement, senior-living specialists are doing what they can to cater retirement communities toward their needs. The problem is, the kids who grew up during the time of free love, free choice and rebellion are not going into their platinum years without a fight.

“Senior-living communities were built for the baby boomers’ parents—not for them,” Lisa Cini, whose company, Columbus, Ohio-based Mosaic Design Studio, one of the nation’s leading providers of design services for senior living, long-term care and health care institutions. “The model needs to change from one of safety, security and dignity, to one of freedom, connection and creativity. It’s time we move away from themed corridors and concentrate on interiors that support the kind of activities boomers will enjoy.”

The term “baby boom” is used to identify the huge increase in births following World War II. Boomers were born worldwide between 1946 and 1964—with 3.4 million born in the first year. In 2011, the first baby boomers reached the average retirement age of 65. Today, there are about 76 million baby boomers in the U.S., representing about 29 percent of the population. Of that large population, only 4.5 percent (about 1.5 million) of older adults live in nursing homes and 2 percent (1 million) in assisted living facilities, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Cini explained that when she started designing for seniors 25 years ago, it was with the World War II and Depression-era generation in mind, called the Silent Generation, in mind. “They’re thankful for a good meal; they’re the ‘we’ generation. They want to leave a legacy for their children and they don’t want to be a burden,” Cini said. The boomers, other the hand, are experimental. “They’re the ‘me’ generation. They’re not trusting of ‘the man,’ and the last thing they want is to be forced to move into a senior-living situation—a commune maybe, but something their parents might have lived in, forget it,” she said.

Cini’s designs have taken a radical change to accommodate this group. Her homes—which include dozens of individual apartments—are a mash-up of hotel-meets-resort-meets commune, and are in places like Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, West Chester, Ohio, and Chicago, Illinois.

“Facility”—as in a senior facility—“is the F-word for them,” Cini said. “When we design for aging adults to ‘live’ vs. exist, we design a ‘home’ not a ‘facility.’

“Facilities are hospitals and places where you don’t want to stay and they don’t focus on Soul Space so that you can be your best you, hence…we never want to design a facility, we focus on designing a home that has items that allow you to live with freedom,” Cini said.

One of the major changes in design is the dining options. Boomers will not agree to a one-stop-shop, cafeteria-style dining room. They want options. (The 1960s watchword would be “freedom.”) So, instead of one place where you go to eat three meals a day and you get a predetermined menu, Cini’s homes offer three to four of what she calls “micro-restaurants,” that have their own personalities. Such as Paxton’s Grill, offering American favorites off the grill and The Chalkboard Café (think Starbucks but with daily fresh baked breads and sweets along with a grab-and-go menu and coffee tea and smoothies), or the Tuscan Grill, offering wood fired pizzas made to order in front of you, farm-to-table vegetables grown in the community garden onsite and signature wines.

The price tag of the moniker of “independent living” isn’t cheap. Residents can pay between $3,000 and $6,000 a month in rent, more in bigger cities such as New York or Los Angeles, as Commercial Observer previously reported. If seniors need “assisted living” or “memory care” facility the rate can be as high as $4,000 to $8,000 depending on amenities, location, square-footage of the residence and other factors.

Keren Brown Wilson has over 30 years of experience in long-term care and supportive housing. She was the principal architect of the Oregon model of assisted living and worked with policymakers in other states who wanted to replicate it. Wilson said that although there’ll always be a place in the market for Continuing Care Retirement Communities (C.C.R.C.s), there’s also a lot of interest in trying to figure out how to layer [amenities] on to independent living for people of more modest means.

“Many of the C.C.R.C.s are now very different than they were 40 years ago,” Wilson said. “For example there’s one in Portland [Mirabella] that is very expensive. It has penthouses with views of Portland. It has a-la-carte concierge services. So the C.C.R.C.s are already modifying themselves to adapt to the preferences of customers who have the resources.”

Mirabella currently houses 44 beds and costs on average about $8,000 per month. Amenities include an art studio, indoor pool, beauty salon, woodworking shop, resident business center, room service, four restaurant-style dining options including a lounge, a formal dining room with city views and a rooftop terrace.

“I think if I were in the C.C.R.C. business I’d be thinking about that next layer of people who can’t afford a million-dollar buy-in or high monthly expenses. I’d be looking at both the horizontal and vertical integration of the model,” Wilson said.

Some senior living communities ask for an upfront fee, some ask for month-to-month payments, and some for both. The cost depends on the type of community and what amenities are available. Low-income seniors can qualify for subsidized programs from the U.S. department of Housing and Urban Services, but generally speaking the monthly cost is determined by the income of the senior.

To meet the demands of the “me” generation there are a plethora of communities to choose from.

In Ocklawaha, Florida, there’s the “toy-friendly” resort for seniors called Lake Weir Preserve. This senior community, which doesn’t charge HOA fees or have amenities since residents travel in RVs half the year, caters to seniors who love their Harleys, big bikes, RVs, boats and old school Buicks, and offers them a place to tuck them away in a five-car garage. “The baby boomer demographic is the largest user of ‘toys’ in retirement. Many will buy their first sports car, or perhaps refurbish a car they had in their teens,” said Adriana Rosas, director of community development at Lake Weir Preserve. “For the last 10 years there has been a steady growth in RVs, motorcycles, and classic car shows,” Rosas said.

In Newton, Massachusetts, there’s a C.C.R.C. located on a college campus called Lasell Village, where residents get in touch with their inner-Berkeley student, requiring them to attend 450 hours of classes a year—complete with Pilates and heated swimming pools. Designed on the scale of a small New England neighborhood, Lasell Village is located on a 13-acre site on the campus of Lasell College in Newton, Mass., a suburban community 10 miles west of Boston.

“Baby boomers are drawn to a community with a vibrant culture that embraces learning and engagement in intergenerational classes, lectures, clubs, and a full roster of fitness programs,” said Anne Doyle, president of Lasell Village, and vice president at Lasell College. “Our educational and health care offerings allow our community to thrive.”

At Lasell, residents are required to commit to 450 hours per academic year, in class, volunteer or paid work, equaling to the average schedule of a full-time student—all in an effort to make sure the senior residents remain active and involved on the campus.

“Along with the entrance fee”—which starts at $450,000 for a 640-square-foot one-bedroom—“there is a monthly fee [of $4,200] that covers an extensive list of services and amenities,” Doyle said. This includes meals, extra educational programs, IT, an on-site convenience store and hair salon.” Units can go for as high as $1.3 million for a 1,900-square-foot apartment.

Not to mention the several communities with multiple golf courses, spas, activity centers and restaurants that rival five-star eateries. At the Fountaingrove Lodge, an LGBT retirement community in Sonoma, California, two-bedroom bungalows demand an entrance fee of $1 million, plus monthly installments of more than $6,000.

Included in the price is continental breakfast, 21 flexible meals, weekly housekeeping, wellness and fitness programs, according to the website. Additionally, residents have access to a fitness center, wine cellar, art studio, swimming pool, salon, theater and even a restaurant captained by a classically trained chef who worked under Wolfgang Puck and as the sous chef at the legendary Chez Nous.

The Rio Verde Community and Country Club in Rio Verde, Arizona, keeps residents active by offering activities such as hiking, cycling and horseback riding. It also has two golf courses. The community’s 1,000 custom-built homes start at about $350,000 and can top $1 million.

“Baby boomers are being a very demanding customer,” Stephen Maag, the director of residential communities for LeadingAge, an association of nonprofit providers of housing and other aging services, told The New York Times, adding that the industry must respond “to a consumer that has pushed back on everything they’ve touched in the last 60 years.”

Ultimately, getting boomers into any kind of senior-living space is a challenge.

Ninety percent of boomers say they’re determined to age in place, according to AARP, and Americans 65 or older have the highest homeownership rate of any generation. Almost 80 percent of seniors own their homes, compared with 35 percent of Americans under age 35, according to Realtor.com.

To make matter worse, according to the Stanford Center on Longevity, 30 percent of boomers have little money set aside for their golden years to pay for the luxe C.C.R.C.s, and among those who do have savings, the median balance is just under $300,000 for boomers born between 1948 and 1953 and closer to $200,000 for those born between 1954 and 1959.

No one is quite sure where this freedom-fighting, autonomous demographic will end up, but what is certain is there will be a very real need for diversity of housing options to satisfy this burgeoning age group in the very near future.

Update: This story was edited to correct the description of the association LeadingAge.