Stuck in the Middle: Smaller Boutique Hotels Are the Odd Ones Out

Lending opportunities abound for boutiques, but who wants them?

By Mack Burke February 19, 2019 10:30 am

reprints

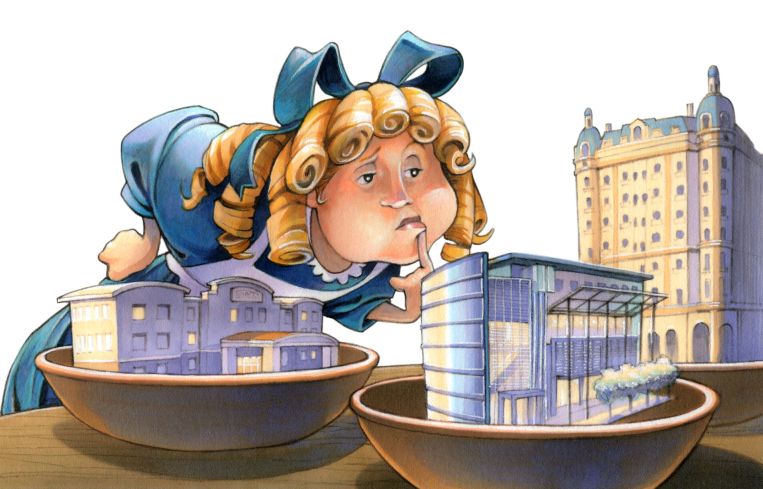

Boutique hotels have a Goldilocks problem.

Hotel financiers must decide whether a lending opportunity is too big, too small or just right.

For many, boutique and independent hotels in the $30 million and under range are firmly on the “too small” side and are viewed as riskier investments. For others, this creates a unique lending niche where the risk-return reward is . . . juuuuust right.

With the market slowing and hotel room supply outpacing demand in some of the country’s major markets, it’s more costly to be a boutique borrower today. That’s coupled with the fact that lenders are shying away from non-branded hotels or ones that don’t demonstrate a surefire record of success.

“[There’s a lot of loan requests on hotel] names that aren’t top-of-the-list for most lenders,” said Mark Fogel, the CEO of Long Island, N.Y.-based middle-market lender ACRES Capital. “There are lenders out there, but the price point is well above where these [borrowers] want to be, and certainly above where you’d be if you were a Marriott or a Hilton.”

Many independent hotels and boutique owners typically chase floating-rate bridge debt in the range of $5 million to $30 million as a short-term solution to keep from putting their asset on the market. Some lenders shy away from refinancing these assets as they can be difficult to underwrite for additonal upside due to uncertainty that’s spawned from a slowed hotel market and today’s late-cycle environment.

“Often [our pipeline is] a good indicator as to what is not hot right now in the marketplace,” Fogel said. “As an alternative lender, people come to us as a second or third option after they test the [commercial mortgage-backed securities] market and the banks just because those are cheaper forms of capital.”

Acres Capital has seen 158 hotel financing opportunities—totaling $3.6 billion—over the last 12 months. “That’s a lot,” Fogel said, as it represents 13 percent of the 1,200 potential deals the firm has looked at over that period.

“[That many] opportunities basically says to us that somebody has turned off the spigot somewhere on what was once a traditional and good source of financing for [smaller hotel assets],” Fogel added. “Right now, the general consensus is if you’ve got a good flag, like a Marriott or a Hilton, in a good market, like Chicago, New York or Los Angeles, you’re going to find financing for that.”

Put simply, alternative lenders are the ones boutique hotels typically go to for refinancing, but these financiers are also wary.

Los Angeles-based private lender Thorofare Capital provides debt on independents mostly out of its short-term, opportunistic bucket of capital, which provides nonrecourse, interest-only debt, ranging from $5 million to $40 million in loan size, with an average loan-to-value of up to 68 percent.

“Underwriting for nonrecourse routes has become more strict and cap rates are stressed heavily on boutique hotels where they usually have a non-institutional owner,” said Thorofare Principal Felix Gutnikov. “But, there’s been a big pick up in refinance requests that are nonrecourse.”

“At the end of the day it’s about making an investment decision and, secondly, it’s more of a basis play focused on cash flow and capital markets-driven underwriting,” Gutnikov continued. “The most important thing for us is who the operator is and if it has specific experience in operating boutique hotels. With the ones we’ve financed, it’s never to a beginner.”

Gutnikov highlighted a recent $17.8 million loan Thorofare provided for the 200-key Mainstay Hotel in Newport, R.I., which he said was interesting because of the asset’s location in a destination market. The sponsor on the deal is planning to reposition the property into a lifestyle-focused boutique.

In contrast, some sponsors have resorted to incorporating a flag in order to gather financing interest for an asset. Amherst Capital Management head of originations Abbe Franchot Borok told Commercial Observer about a recent $26 million loan the firm made to a non-institutional family owner for the purchase of an independent hotel in Davis, Calif., where the borrower’s business plan is geared to actually transition the asset from a boutique into a branded hotel. “Our borrower was buying it and planning a renovation process into a Hilton Garden Inn,” she said. (Amherst declined to provide the name of the sponsor or additional details.)

Gutnikov said many lenders haven’t fully warmed to boutique assets just yet given the state of the market, which has become slightly oversaturated.

One broker at a prominent advisory firm who is currently in the market with over a dozen boutique hotels argued that these independent hotels can actually prove to be more valuable than, say, a branded asset of the same size.

“Properties that are not branded have more value because they’re unencumbered,” the unnamed broker said. “If the property is showing good cash flow and is unencumbered, buyers will pay more when it goes up for sale.”

While alternative lenders certainly aren’t the only source of capital, boutique hotels can, indeed, get the necessary financing needed, but it costs.

“I don’t see a serious lack of financing from any source,” the unnamed broker said. “We’re doing a handful of deals on smaller, independent hotels that are stabilized. If it’s stabilized and the cash flow is sufficient, life company money is available…and CMBS money is also available. Then you have the debt funds and some CLO players quoting deals as well. I really haven’t seen the market as flush as it is now.”

Acres’ Fogel said, “We make these loans on stable hotels…we’re charging LIBOR +8 and +9 and that’s way above where the CMBS market is right now, but, you know what? There’s really no choice right now.”

“People are just taking bridge loans from groups like ours and saying, ‘Let’s wait for another day,’ ” Fogel added. “Somebody is going to make the loan, but not at the loan-to-value that these [borrowers] might want…and the rate is going to be 2 to 3 [basis] points wider than the flagged assets.”

While sentiment from banks would indicate that they’d prefer to stay on the sidelines when it comes to financing these hotels, Thorofare’s Gutnikov said he has seen banks get involved in financing if the sponsor is willing to accept recourse.

“Banks are still major players but more constrained on loan-to-cost and overall volume of business as they might just reserve a pool for their best relationships and clients,” said Matt Mitchell, a senior vice president at hotel construction lender Hall Structured Finance. Mitchell said there’s certainly been fewer options for less established developers, and that’s “where we’ve seen an opportunity. We’re a contrarian lender, where we look for space that we feel is underserved.”

Fogel said, “Hotels move day-to-day with the times. It’s very hard to pinpoint, especially in markets outside gateway cities. Any miss on revenues by 10 percent or more is a big deal. You don’t get misses like that, generally, in the other asset classes. Banks just look at hotels—outside of flagged hotels—as a very high-risk investment situation.”

Thorofare’s Gutnikov said he’s seen entrepreneurial life companies and mortgage REITs getting more involved with smaller hotel financings over the last 12 months, most likely trying to get in while yields are high.

“For full-service hotels in major markets you’ll see more of an 8 to 9 debt yield, while with limited-service hotels in second and tertiary markets might be an 11 to 12 debt yield. You see a lot of borrowers getting floating-rate [loans] for a [transitional asset] to grow cash flows,” said the unnamed broker.

“People will go with a floater…until they can stabilize it,” the unnamed broker continued.

Since 2016, national hotel market fundamentals have slowed but are stable. “With the run up in hotel performance, it’s tough for a lot of us to continue to underwrite additional upside,” Gutnikov said. “In the last 60 days, we’ve gotten over $200 million in [floating-rate, bridge] loan requests” from hoteliers looking for capital on deals in Manhattan and Brooklyn, Baltimore, Miami, and across Southern California in Napa Valley and Laguna Beach.

Fogel said he sees just about every deal that passes through Acres and “it just clicks that there are so many more hotel deals [needing financing]. I didn’t get that sense two or three years ago.”

CMBS conduits deemed too rich with hotels—branded or otherwise—aren’t well-received in today’s market, and the collateralized loan-obligation space, although focused on smaller, floating-rate loans on transitional opportunities, hasn’t yet fully embraced the boutique product.

CMBS rejects these boutique deals because “of the treatment they get from ratings agencies and B-piece buyers,” Gutnikov said. “[CMBS would] prefer less cyclical property types like industrial. Hospitality is just risker, so when [conduits] get priced, bonds with less hotel compression get better treatment.”

Fogel said he recently looked at a $30 million branded hotel deal in Chicago and was told it got 12 CMBS quotes. More often than not, the boutiques aren’t so lucky.

“If I was a CMBS lender, I wouldn’t want to [include independent hotels] either,” the unnamed broker, who has spent time in the realm of structured finance, said.

Is it just cold feet? Hotel occupancy outperformed last year, by some standards, following a nearly 10-year boom for the sector after the real estate industry emerged from the financial crisis, but analysts expect the figure to flatten in 2019 and possibly turn negative in 2020.

What’s getting put in CMBS right now is the “best of the best,” Fogel said. “There are a lot of hotel deals in the CMBS world that are coming due and were over-leveraged and that’s what‘s getting refinanced these days. That CMBS market was huge back in 2007 and 2008 and now it’s contracted greatly.”

Although CMBS remains strict and selective in their inclusion of small and independent hotel assets in conduit pools, that doesn’t mean that the space is completely discriminatory.

Brokerage firm Sonnenblick Eichner recently securitized two loans—$5 million and $6 million—on two independent hotels in Palm Springs, Calif. The two 10-year, fixed-rate loans—on the 22-room Sparrow’s Lodge and 27-room Holiday House, respectively—were securitized by Bank of America and there were “a lot of CMBS lenders [vying for it],” Principal Elliot Eichner said. “You never just have one.”

Sparrow’s Lodge and Holiday House, though, are unique. Both hotels are very popular destination locations in Southern California and have been ranked in a variety of high-profile travel publications and also sport a strong sense of exclusivity that appeals to the growing millennial demand for lifestyle-focused products and independence.

“There are a lot of lenders that will only lend on flagged hotels, but I think that’s changing,” Amherst Capital’s Franchot Borok said. “With the current trends in hospitality, that has created more interest in soft-branded hotels that are affiliated with the larger brands but aren’t directly flagged. Boutiques are certainly more difficult to finance right now, but those represent a larger portion of the hotel sector.”

“We think it’s more of a challenge to find refinances in smaller- to middle-market loan sizes,” she added. “The lending perspective…is that the capital is not as efficient with the small loan size, and that’s more pronounced in hospitality. That’s a sector that’s more volatile than the other food groups. Lenders put a much higher level of focus on the credit review.”

Although it’s unclear when the current extended real estate cycle might pivot downward, many players remain wary of a possible economic recession, which obviously drives strategy behind boutique lending.

Franchot Borok added, “There’s a much smaller bucket of lenders who are active in [lending on boutiques and to lesser-known sponsors]. Hospitality assets are the first to correct, and we’re late in the cycle. You need a steady hand on the wheel, a group who can manage through cycles and weather market conditions.”