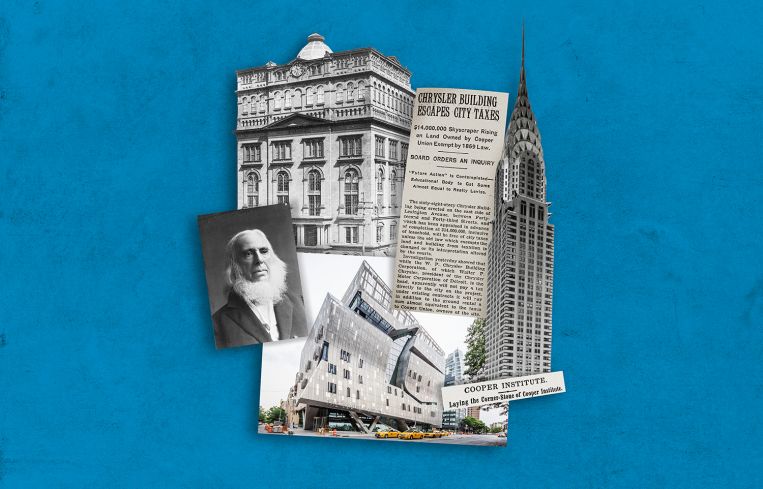

Cooper Union Makes Over $50M a Year From the Chrysler Building. But Is It Enough?

By Chava Gourarie February 19, 2019 11:00 am

reprints

In January, when it got out that Tishman Speyer and the Abu Dhabi Investment Council were putting the Chrysler Building on the market, there was a detail that might have escaped notice.

They don’t fully own the landmark skyscraper.

The property isn’t owned by a church, a real estate investment trust or one of the big New York real estate families. The land where the 77-story tower was built is owned by The Cooper Union, the elite, East Village school.

In 2019, Cooper Union will make more than $50 million in rent and tax income off the Chrysler Building—its main asset. And yet, the historic institution, founded by Peter Cooper with a mission of providing education for all, has been in such a financial crisis over the last decade that it will be charging tuition for the fifth year in its 160-year history.

The arts, architecture and engineering school began its tuition about-face in 2014, despite vehement protest from students and faculty, a lawsuit and an investigation by the attorney general’s office that uncovered a decade of excess, negligence and bad management of the school’s finances. In 2015, a court mandated the college to seek ways to return to free admission, and the college, under new leadership, is in the midst of a 10-year plan to do so by 2029. And a recent spike in rent from the Chrysler building is critical to making this happen.

“We have a 10-year plan in place to return to free tuition for all our undergraduate students, and the lease is a core component of that,” the school’s president, Laura Sparks, told Commercial Observer.

While most of the Cooper Union community is pleased to see the school begin to right the ship, many are also skeptical that the 10-year plan will be achieved, and if the school can maintain its culture until then.

“Things are going in a positive direction,” said Brian Rose, a member of the school’s alumni association council. “I support [the plan] with as much enthusiasm as I can, but I remain somewhat skeptical about where it’s going to go.”

Currently, the school has a lease agreement with Tishman Speyer, which bought the Chrysler Building in 1997, then sold 90 percent of it to the Abu Dhabi Investment Council a decade later. Under the terms of the lease agreement, which was renegotiated in 2006, Tishman Speyer paid a fixed rent of $7.5 million a year to the school through 2018 plus a share of the building’s income. In 2018, the rent jumped to $32.5 million until 2028 when it will increase again to $41 million, and then to $55 million in 2038.

In addition, because of a tax arrangement with the city, the school receives all the property taxes from the Art Deco tower that would otherwise go to the city. Tax assessments vary by year but in 2018, the tax income from the building was projected to be slightly over $20 million.

The school also receives tax or rent revenue from several additional properties, including the 400,000-square-foot office building at 51 Astor Place and the luxury residential condominium building at 445 Lafayette Street, both built on Cooper-owned land.

So how did a school with an asset as valuable as the Chrysler Building end up so deep in the hole that it chose to betray the school’s 155-year old mission?

That too is related to the Chrysler Building. And to a hulking, metallic building at 41 Cooper Square, the school’s new academic building, completed in 2009 at a cost of $164 million. To build it, the school mortgaged the land under the Chrysler Building to secure a $175 million loan, without a viable plan to pay it off.

In the 1850s, Peter Cooper, a wealthy landowner and philanthropist, founded The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art with the intention of making higher education “open and free to all.” Cooper assembled a collection of land near what’s now Cooper Square and built the Foundation Building at 7 East Seventh Street to house the school, which opened in 1859. “That really was a game changer for the entire country,” said Kevin Draper, a New York City historian, because until then, “higher education was just for the wealthy.”

Cooper bequeathed land to the school in the hopes that it would pay for the school’s operating costs. “His thought was, ‘I’ll take a lot of my real estate holdings and tie them to the university,’ ” said Draper, so that as operating costs increased, real estate values would rise simultaneously, and “they would cancel each other out.” Several decades later, Cooper’s heirs added the land at Lexington Avenue and East 42nd Street, on which the Chrysler Building was later built to the school’s endowment.

Over the 20th century, Cooper Union became renowned for its quality arts, architecture and engineering education. Without cost as a barrier to entry, anyone could apply, which allowed the school to be selective (in 2010 when Newsweek named it the most desirable small school in the country, it had a 9 percent acceptance rate, lower than many Ivy League schools), and its alumni include an impressive roster of artists, architects and engineers such as the inventor Thomas Edison, Batman’s co-creator Bob Kane, and Milton Glaser, the designer of the I Love New York logo, among others.

The school had its share of financial trouble over the years, and operated at a loss for many years, but it wasn’t until the last decade that the institution was in danger of closing its doors. In 2011, under president Jamshed Bharucha, the truth about the school’s dire financial straits, which had been steadily worsening for year, began to emerge, along with the possibility that Cooper might charge tuition.

A turbulent few years followed in which students, faculty and alumni organized to stop the board from implementing the change. Student protesters occupied Bharucha’s office in the summer of 2013 calling for his resignation, a group called the Committee to Save Cooper Union filed a lawsuit against the school, and the attorney general’s office began investigating how the school had reached the point that it did.

The investigation pointed back to the early 2000s, when the newly installed president, George Campbell Jr., decided the school needed to reposition itself for the new millennium, and for that, it needed a brand new building. In 2006, Campbell, along with a board of trustees, decided to fund the new building at 41 Cooper Square with a $175 million loan after failing to raise the funds from alumni and donors as they had originally intended.

MetLife agreed to lend the school the funds, and the loan was secured by a mortgage on the Chrysler Building land. It was because of that loan that the school renegotiated its lease with Tishman Speyer with terms amenable to MetLife. The terms of that deal appear to have vastly underestimated the value of the building. In 2010, Steven Rubenstein, then a spokesman for Tishman Speyer, told The Wall Street Journal that the 2018 rent represented a two-thirds discount from the value of Midtown Manhattan space at the time. “This discount was a great deal then, it’s a great deal now and it’s going to be even better in 2018 when it kicks in,” he said at the time. A spokesman for Tishman Speyer declined to comment on the quote.

The 30-year mortgage also came with a hefty prepayment penalty, which in 2012 would have been $81 million, according to court documents. Since 2006, Cooper Union has paid $10.3 million in interest payments, and this year, the principal payments of $5.5 million per year begin.

The AG’s report on the findings from its investigations unequivocally concluded that the loan was one of the key sources of trouble, calling it “part of a complex and risky “ plan. “The plan immediately began failing, with its key assumptions steadily unraveling over the first two years,” the report continues. “When the stock market collapsed in late 2008, the damage already promised by the plan’s failure was greatly magnified and transformed the entire project into an albatross. The new building was finished, but the school’s finances were broken in the process.”

The plan to pay it off was reliant on four assumptions, including a fundraising goal that the board had no evidence would materialize, and no contingency plan if it didn’t, the report states. Campbell has disputed the investigation’s findings.

The new building, completed in 2009, which houses the engineering school, was designed by architect Thom Mayne and cost $164 million to build. Its distinctive metallic facade with a transparent ground floor, opening up to an airy interior, was meant to highlight the spirit of the school and its commitment to “free and open to all,” per printed interviews with the architect at the time.

Rose, the alumni council member, who is also an architectural photographer, said he sees the building as a failure on the part of the leadership that oversaw its construction. “When it first went up I was excited that Cooper was doing something really cutting edge and modern,” he said. “But once I found out that the school had basically mortgaged its future, literally by taking out this huge loan, I was dismayed and looked at the building as a big mistake.”

Once the loan and lease agreement were locked into place, most of the income from the Chrysler Building was eaten up by loan payments, and the school was reliant on donations and a small endowment in order to keep the school out of the red. By the time they were forced to acknowledge the financial condition of the school, in 2011, it was in danger of closing, and the board claimed to have no choice but to charge tuition.

Casey Gollan, an alumnus and adjunct professor at Cooper, was in his sophomore year as an arts student at that time. “There was just kind of a groundswell of frustration, and it built up to a bunch of students deciding to that we needed to do something to raise much more attention,” he said. In 2011, the students painted the lobby of the architecture school black in protest, and in 2012, Gollan was one of 12 students who barricaded themselves on the top floor of the Foundation Building and announced they wouldn’t leave until the school reiterated its commitment to free tuition, along with several other demands.

The protests continued from there. Several board members resigned but the board nevertheless moved to end free tuition. In 2015, the Committee to Save Cooper Union filed a lawsuit to block the school from charging tuition, and the AG joined the melee with its own investigation. By September of that year, the school, Save Cooper Union and the AG’s office agreed to a settlement in which the school committed to finding a way to return to free tuition. The agreement also ended or limited the reign of any of the leadership that had been around in 2006 and installed a financial monitor at the school for a 10-year term.

Cooper Union formally adopted a plan in March 2018 to return the school to free education in 10 years, by incrementally increasing the amount of scholarships provided. The plan, colloquially known as the “plan to free” is contingent on the school building up $250 million in reserves during that time, which it plans to do through its real estate holdings, fundraising and cost-cutting, Laura Sparks, Cooper’s president, said. Cooper already covers 76 percent of tuition for students on average, according to documents from the school.

But Gollan, the former student activist, said the school seems more concerned with regaining strong financial footing than in restoring the school’s social mission. “When they say, ‘plan to free,’ they mean the plan to a gigantic system of risk management so that they never get into trouble again, and it happens to provide scholarships,” he said.

And, despite the fact that the income bump from the Chrysler Building has been anticipated and worked into every financial model during the crisis, for Gollan, it still rankles.

“If you were to really look at the revenue that Cooper gets from something like the Chrysler Building and other properties and investments, I think you can clearly make the case that a free education today and tomorrow and long into the future would be possible,” Gollan said. “But I think it’s been reframed as a model that doesn’t work.”

“We spent a lot of time with our community,” Sparks said, receiving input regarding the accepted plan. “They understand that as we move to free tuition, our goal is to make sure that’s sustainable in the long run. “

Sparks also confirmed that a potential sale should have no effect on the school’s finances, since the lease agreement is locked into place with the lessee.

The building is being marketed by Bill Shanahan and Darcy Stacom of CBRE, though it’s unclear at what price point. In 2007, then-owner Tishman Speyer sold a 90 percent stake to the Abu Dhabi Investment Council for $800 million.

Its pedigree makes it an attractive investment, though the existing ground lease, and the rental income a building of its age can generate limits how much a buyer will be willing to pay.

Whatever the building sells for, the fate of one of New York’s historic institutions remains tied up in the land underneath it.