City Unveils Plan to Allow More Development in Industrial North Brooklyn

By Rebecca Baird-Remba November 19, 2018 5:00 am

reprints

The Department of City Planning is about to release a long-overdue plan to encourage taller commercial buildings in the industrial zone that stretches from Greenpoint to Bushwick in northern Brooklyn, Commercial Observer can first report, a week after the city and the state revealed a controversial proposal to build Amazon’s new HQ2 campus on industrial land next door in Long Island City, Queens.

The rezoning process kicked off three years ago when Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a ten-point, $115 million plan to create more job opportunities and protect businesses in New York City’s manufacturing areas. After de Blasio unveiled the manufacturing initiative in November 2015, the mayor and his planning department promised to study the North Brooklyn Industrial Business Zone (IBZ). By the end of 2016, they said they would release a set of policy recommendations that would enable more development and prevent industrial tenants from being displaced. The 1,066-acre swath of land along Newtown Creek stretches from the northern tip of Greenpoint and winds its way south through East Williamsburg and Bushwick. The area has long been home to heavy manufacturing uses, like wholesale food distribution, concrete plants and waste transfer stations, but in recent years, artists, tech companies and higher-paying light industrial tenants (think furniture makers, 3D printing services, film studios) have begun to move in. And in some parts of the neighborhood, landlords have started pushing out industrial businesses with the aim of either selling to hotel developers or converting loft buildings to office space.

Also, developers, business owners and planners have long pushed to reform industrial zoning throughout the five boroughs, arguing that the parking-heavy, low-density manufacturing zoning created in 1961 stymied development and made it tough for manufacturing businesses to grow. The parking requirements baked into the zoning code make it difficult to build in the city’s industrial neighborhoods, because the necessary car storage takes up too much space on small lots and is often prohibitively expensive to build.

“There are a lot of manufacturers in the city that would expand but can’t because they’ve hit their density caps,” said Armando Moritz-Chapelliquen, who oversees economic development programs at the nonprofit Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development. “So increasing the density in industrial areas is crucial if you want to allow businesses to grow and increase the number of jobs.” He added that “the parking and loading requirements were onerous and needed to be right-sized.”

The city’s promised deadline for the study came and went two years ago, and industrial business advocates and local activists became increasingly frustrated. They began to assume the proposal was dead, said Leah Archibald, who was heavily involved in the planning process for the study as executive director of industrial business group Evergreen Exchange. Then, out of the blue, the mayor told a reporter at a press conference earlier this month that the North Brooklyn industrial zone study would be out before Thanksgiving.

The new policy also arrives six days after de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled a widely criticized plan to build a new 4 million-square-foot headquarters for Amazon just across Newtown Creek in Queens. Some sources familiar with the rezoning questioned the timing of the Brooklyn industrial report’s release, particularly because it had sat on the back burner for two years.

The 167-page draft report obtained by CO would allow slightly taller, denser buildings across the manufacturing neighborhood and dramatically reduce parking requirements for new buildings and expansions. City planners hope that it will let existing industrial businesses grow and encourage the construction of new office and industrial space near the area’s two L train stops. Although the industrial business zone has lost nearly 30,000 jobs since its peak employment rate of 42,300 workers in 1969, it gained 2,270 jobs—1,200 of which were industrial—from 2010 to 2016, according to data from the state Department of Labor. Roughly 19,500 people worked in the North Brooklyn IBZ in 2016, 77 percent of them in industrial jobs.

“With nearly 20,000 jobs and a wide diversity of businesses, the North Brooklyn Industrial Business Zone is one of New York City’s most important job-producing centers,” DCP Director Marisa Lago said in a statement. “As this administration works to foster more good-paying jobs in a broad range of business sectors, the North Brooklyn Industry and Innovation Plan zeroes in on key goals and tools to modernize outdated industrial zoning.”

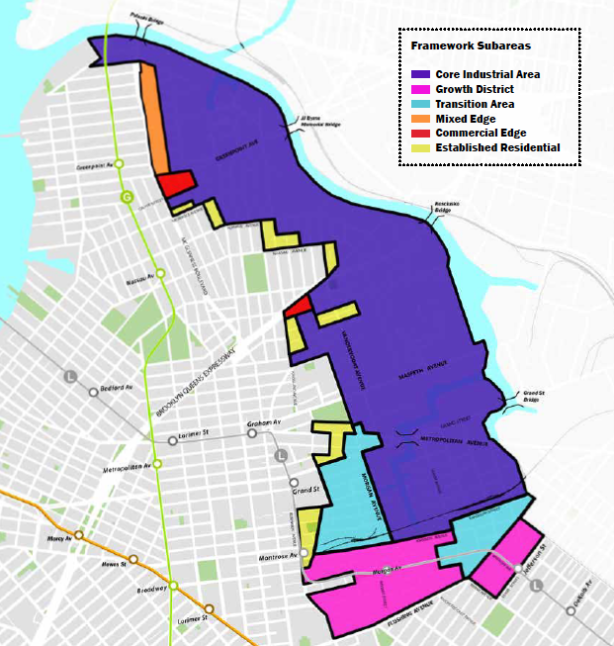

The plan calls for the sprawling neighborhood of warehouses and loft buildings to be split up into three distinct zoning areas. The “core industrial zone” occupies two thirds of the neighborhood and includes a large, rather remote area along the creek in East Williamsburg and Greenpoint. It will be upzoned to allow buildings twice as large as the square footage of the lot they sit on. The new zoning will ban nightclubs and concert venues, which have proliferated in East Williamsburg and Greenpoint in recent years, and limit the size of new retail spaces, restaurants and offices. Then there will be two small “transition zones” west of Morgan Avenue and south of the freight tracks. A yet-to-be-determined incentive will be written in the zoning code there to encourage developers to build or preserve industrial space in exchange for the right to include more office space in their projects.

The third area, dubbed the “growth district,” will encompass several blocks of mid-rise loft buildings near the Morgan Avenue and Jefferson Street L train stops. The rezoning will allow new four- to six-story commercial buildings, with no limits on the kinds of business that can inhabit them. Planners hope that new new office space and retail will follow.

Industrial business advocates were mostly thrilled with the proposals.

“This is a significant blueprint for how we can move zoning forward in the [industrial business zones] citywide,” said Moritz-Chapelliquen. “The fact that there’s a meaningful core industrial tool in this plan is real progress.”

But they called for limits on the type of development that could happen in the growth district and for the Department of Buildings of the new rules governing the kinds of tenants that could operate in the core industrial area.

“If we’re going to channel development, we think that any development should have some element of working class jobs,” said Archibald, referring to the growth district. “Maybe rather than an across-the-board upzoning, which is what they’re talking about, maybe create an incentive program, so that if you build an office building, keep one floor of industrial.” She added that she was concerned about “enforcement to adequately oversee any use group limitations” in the core industrial area.

Councilman Antonio Reynoso explained in a statement that he was “incredibly pleased” the study was finally being released. “Industrial jobs provide a critical pathway to the middle class for folks with low educational attainment and/or limited English proficiency, with better wages and opportunities for advancement not present in the retail and service sectors. However, as the surrounding area gentrifies, manufacturers are facing competition from non-industrial uses such as offices, nightlife, and retail. I believe the restrictions on non-industrial uses proposed in this study will provide the necessary protections to allow the North Brooklyn IBZ to retain its industrial character and continue to serve as an economic hub for local communities in the years to come.”