The Invisible Hand of Gotham: A Professor Explains How Economics Shaped the Skyline

By Matt Grossman September 4, 2018 12:30 pm

reprints

You might not know it from the shoves and glares exchanged on the Lexington Avenue subway, but an affinity for extreme proximity is the lifeblood of New York City.

That, at least, is an argument advanced by Jason Barr, an economics professor at Rutgers University–Newark who has dedicated much of his career to studying the ways free-market incentives have shaped and influenced Manhattan’s skyline.

“Skyscrapers start with economic demand: the desire of people and businesses to be tightly packed in the same location,” Barr told Commercial Observer in an interview last month.

It might seem an obvious point. But the professor’s new book, Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers—just out in paperback—crackles with reminders of how Manhattan’s cityscape inextricably owes its form to economics. Born of thousands of individual decisions about what to build, where to build and how tall towers ought to rise, the skyline represents to Barr the ways the market’s invisible hand has played the leading role in shaping the island’s development.

Larger-than-life personalities loom over the Big Apple’s real estate industry. But Barr, who also blogs about skyscrapers on his website Skynomics, is convinced that no one developer can ever singlehandedly alter the agenda set by the eternal forces of supply and demand.

“To put it succinctly, the battle for place leads to a land dance, a kind of multiple-partner waltz around space,” Barr writes in the book. “Each [developer and financier] tries to be the leader and take the dancers in a particular direction, only to get a response to go in a different direction.”

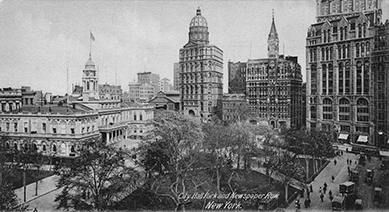

A story from the early days of the city’s professional class illustrates Barr’s point. In the late 19th century, assertive moguls like Horace Greeley, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer dominated New York’s newspaper industry. But despite their wealth, power and desire to differentiate their publications, a set of market incentives magnetically drew all of the city’s major newspapers to headquarters that rose within blocks of each other on the streets immediately southeast of City Hall.

“They were clustering around the printing presses and clustering around the seat of government,” Barr said. “It was also useful for attracting talent. If you were a young journalist and wanted to make a name for yourself, you’d show up [in the neighborhood], visit the newspapers and say, ‘Hire me!’ ”

As a result of the economic benefits that nearness bequeathed, each paper was willing to spend millions to build its own skyscraper on the block to house its entire staff in close proximity to the action, rather than take up tenancy in cheaper areas elsewhere. Thus, economic forces gave rise to some of the island’s first skyscrapers even while countless acres of land to the north had yet to be developed.

Of course, Gotham wouldn’t be much of a city if developers had never set up cranes north of Canal Street, and the office towers of Midtown also owe their pedigree more to piecemeal economic developments than to any individual developer’s bold scheme. Barr’s recent conversation with CO—in Union Square Park, of all places—afforded a handy perspective on mass transit’s role in drawing development in Manhattan inexorably northward.

“Streetcars allowed people to move uptown, which in turn allowed places like Union Square to begin to develop as retail, restaurant and entertainment districts,” Barr said. “It was really around Madison Square Park that the first ‘midtown’ developed.”

Dating back to the city’s earliest days as the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam, the port at the island’s far southern tip had always been its critical economic engine, Barr said. The city’s first generation of skyscrapers, clustered in that area, but not until horse-drawn trolleys emerged did neighborhoods north of Houston Street offer anything approaching the commercial density to support buildings that aspired to skyscraper heights.

Gradually, toward the end of the 19th century, the emergence of the Ladies’ Mile retail district along Fifth Avenue between East 14th and East 23rd Streets brought sufficient commerce to the neighborhood leading to small businesses beginning to clamor for office space nearby. Skyscrapers became practical as tenants demanded convenient offices from which they could serve the crowds that department stores, like Bergdorf Goodman and Lord & Taylor, brought to the neighborhood.

“In 1902, the first skyscraper north of Lower Manhattan was the Flatiron Building, which was very much designed to rent space to smaller tenants like architects and insurance companies,” Barr said. “[At the time], you’d mostly see renters there that were related to the local economy.”

Studying how changes in rents, land values and the prices of construction materials evolved over the 20th century, Barr created a model that seeks to isolate the factors that explain the volume of skyscraper construction over time. His model shows that construction should have peaked during economic boom years like the mid-1920s and the period from 1984 through 1994, a pattern that closely mirrors the historical reality. During times of economic scarcity, on the other hand, new construction almost vanished. As the Great Depression sunk commercial rent rates and World War II created an extreme scarcity of raw materials, the city recorded practically no new skyscraper building whatsoever between about 1935 and 1946.

As the economy surged after the war ended, developers embarked on an office-tower building spree that hardly let up until the 1970s, and that populated Midtown with most of the modernist towers that that neighborhood’s legal and finance tenants inhabit to this day. But Barr’s data reveals that, even as rents soared during that period, there was in fact no overall tendency for buildings to grow any taller over the second half of the century.

“The average trend was actually flat until the last 10 years or so,” Barr said in the interview. “Part of that was the cost of building taller and taller. You could say that the balance of cost and benefit always seemed to put a cap on the tallest buildings you’d see.”

More recently, a unique set of economic incentives has conspired to shape the skyline in a new way. Technological advancements—themselves demand-driven, of course—have made a new slew of pencil-thin “supertall” condominium towers not just feasible but also tremendously profitable in Manhattan.

“The supply and demand factors—they’re all working in favor of these [condo] buildings today,” the professor said, citing examples like 432 Park Avenue and 53 West 53rd Street. Via improvements in wind-bracing technology and the use of mass dampers to stabilize a lightweight frame, it’s now practical to build 100-story towers on slim foundations, Barr said, saving developers from the need to buy huge plots of land to support tall towers.

Even economic forces as broad as global income inequality have played their part in enabling the supertall condo boom.

“If you make an apartment building thin, every apartment is kind of like having a penthouse. There’s a tremendous demand for that,” Barr said. “The concentration of wealth in the world has created a giant pool of investors for these condos.”