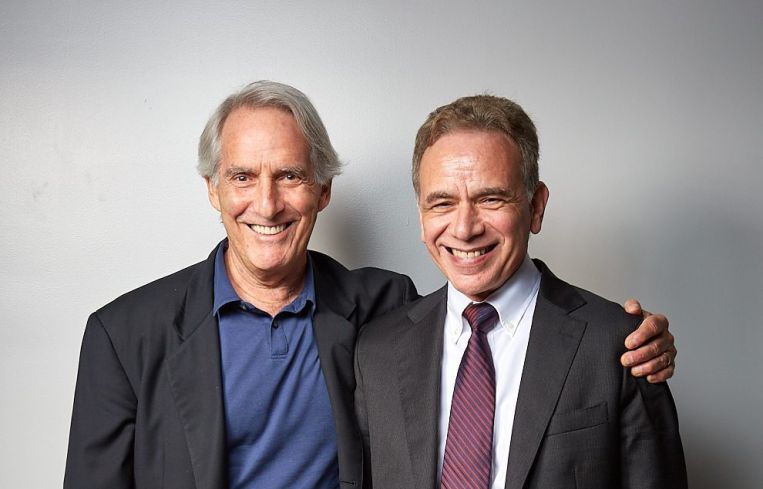

Jay Seiden and Alvin Schein Talk the Ins and Outs of NYC Affordable Housing

The self-proclaimed 'Mantle and Maris' of real estate law discuss property taxes, 421a and the de Blasio administration's Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program

By Rey Mashayekhi July 31, 2018 11:00 am

reprints

There may be larger, more prestigious real estate law practices in New York City than Seiden & Schein. But when it comes to the realm of affordable housing—and the art of helping developers navigate a convoluted regulatory terrain involving myriad tax incentives and zoning requirements—the firm’s partners, Jay Seiden and Alvin Schein, are arguably at the top of the game.

The pair started their eponymous firm in 1996 after careers working for various real estate-focused practices in the city since the 1970s. Brooklyn native Seiden brought to the table his expertise in property tax issues and real estate tax benefits programs, while Schein—the son of Holocaust survivors who was born and raised in Canada but moved with his family to Far Rockaway at the age of 10—had honed his skills in the areas of condominium and cooperative development, as well as affordable housing regulations.

Today, their 13-attorney boutique operation is one of the city’s most sought-after and highly regarded firms when it comes to assisting developers in bringing often-complicated affordable housing projects to fruition. In addition to claiming hundreds of 421a and inclusionary housing developments to its name, as well as hundreds of offering plans for condo and co-op projects across the city, Seiden & Schein also guides clients through lesser-known tax incentives like the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program (ICAP), which applies to non-residential buildings and the non-residential portions of mixed-use buildings. While those practice areas constitute the firm’s bread and butter, it is also active in the more commonplace realms of property and development rights transactions, leasing and financing.

The 74-year-old Seiden, who lives on the Upper East Side with his wife (they have two adult children and two grandchildren), grew up in Flatbush as a Brooklyn Dodgers fan before the baseball team’s move to Los Angeles in 1958. But that doesn’t stop the 67-year-old Schein, a Yankees fan who also lives on the Upper East Side with his wife (and who also has two adult children), from referring to the duo as “the Mantle and Maris of real estate development,” to Seiden’s chagrin. Indeed, Schein claims their firm has worked on more 421a and inclusionary housing projects “than any firm in the city.”

The two men recently sat down with Commercial Observer at their offices at 570 Lexington Avenue (also home to the Real Estate Board of New York) to discuss their careers to date and a range of issues facing the city’s real estate development market—from a flawed property tax system to how developers have responded to both the new Affordable New York Housing Program (which replaced 421a last year) and the de Blasio administration’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program.

Commercial Observer: How did you both come to find real estate law as your practice area?

Jay Seiden: Most of the time, you get into something accidentally. I started off back in the early 1970s doing a lot of J-51 work; the renovation of rooming houses on the west side of Manhattan was a big thing at that time. Hotels were being converted, office buildings and loft buildings were being converted—it was kind of the cutting edge of that. I became a specialist; at that time, there were maybe two or three lawyers in New York who understood the [real estate] tax programs. And there are still only two or three lawyers in New York who do.

The tax programs have always followed emerging, new areas. Soho became very important, because you had all these illegal multiple dwellings, and the J-51 program allowed [redevelopment] to get done. [Brooklyn’s] Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope—those were sort of the emerging areas. And then 421a became really the number one program, because politically, [former New York City Council member] Ruth Messinger and the City Council became very concerned that there were too many giveaways to developers.

In the early 1990s, we also started to do a lot of 421g work, incorporating more residential development in Lower Manhattan. We represented Rockrose and Joe Moinian and we were really the firm that was doing most of the 421g work.

And then all of a sudden, we were doing a ton of new development work. The 421a certificate came into play, and a couple of our clients—Sol Arker [of Arker Companies], Peter Fine [of Atlantic Development Group], Ron Moelis [of L+M Development Partners]—were guys who were building on those certificates.

Alvin Schein: In my case, when I first graduated law school, I was working in a very small practice out in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, which did what consumers needed—real estate, wills and estates, things like that. But that’s not what I wanted; I wanted to come to Manhattan. I liked real estate, and I answered an ad in a law journal; it was a small firm that did J-51, condo work and some 421a at the time. That firm actually competed with Jay’s firm, because we had very similar practices—we represented developers, we did co-op conversions. The way we worked is clients would come in for one skill set, let’s say J-51, and at the end of the J-51 period, now that they’re faced with full taxes, what are they gonna do? The rents were very low because of rent stabilization at the time; the exit strategy was to do a co-op conversion. That’s really how I got into co-op and condo work, which is a major part of our practice here.

Things happen not because you necessarily choose them, but because it’s the right thing at the right time. Years later [in 1995], Jay and I got together when, for whatever reason, my firm was closing and his firm was closing. We knew each other, we got together and we decided to start a whole new practice. At this point, I don’t even know the exact number of clients we have, but almost all of the major developers in the city use us for something or another.

How many affordable housing projects is the firm currently working on?

Seiden: I would say 50 projects under the new [Affordable New York Housing Program] and approximately 75 under the old [421a]. With the new [program], you can’t file until a project’s been completed; the old 421a, you could start the process early on, as soon as commencement of construction.

So developers don’t know that they’re going to qualify for the tax abatement until they finish a project?

Seiden: Well, we know. We write a lot of opinion letters. To take a step back, it was actually in this room that NYSAFAH [the New York State Association for Affordable Housing] was started, right here. I was on the executive committee from day one, and Alvin was involved from day one. Sol Arker was in here along with Ron Moelis, Peter Fine, Jeff Levine—all of the guys that were evolving into affordable housing developers, they were in this room and they all became clients of ours. Alvin was instrumental in writing the zoning resolution as it related to [the city’s Inclusionary Housing Designated Areas program, created by the Bloomberg administration in 2005].

Schein: Jay’s overstating that I actually wrote the zoning resolution, but I did have a lot of input when rules were being made. We had meetings at [the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development] about how the rules should be drawn, especially in terms of for-sale housing under the inclusionary program. At that time there was a big push for not just rental housing, but for home ownership, which fit into our bailiwick because we’re very interested in condo development and co-op development, and with tax exemptions that was a perfect fit.

In 2001, we did three co-ops on upper Madison Avenue in Harlem that were all entirely affordable; like, three 100-unit buildings in a row. This was a great thing for Harlem because it was all abandoned along Madison Avenue in that area, there was a great need for housing, and people wanted for-sale housing. The new administration does not care about for-sale housing; there’s almost no for-sale affordable housing being created right now.

Seiden: And they don’t want any condominiums to get 421a, period.

It was such a big issue in the industry when the old 421a program expired in January 2016. It seemed like no new rental projects were getting into the ground afterward.

Schein: Because the taxes were too high.

Seiden: You couldn’t build, really, in New York City without 421a. The tax assessments in the city are so dramatically high to where your tax bill would be equal to 30 percent of your gross rents, give or take. Guys couldn’t go into projects without 421a, and the lapse was all political. You had [Gov. Andrew] Cuomo fighting with [Mayor Bill] de Blasio, you had the unions [versus] the real estate board, and there was really a lapse period of over a year. So no one could go into the ground, or wouldn’t go in, until they knew they had a project eligible for 421a.

And the other side of it is, there’s still an evaluation—from a lot of the older developers, in particular—about whether or not they can give up 25 percent or 30 percent of their units to affordable housing. That really depends upon the land prices. It’s interesting, a lot of the older guys are not building; a lot of the new guys are doing the jobs. A lot of the clients that are in the practice now were not guys that were known in the city five years ago.

Like who?

Schein: Adam America is one of our clients, a new developer. There are groups backed by Asian money, and we see a lot of projects going up with investment money from other countries.

Seiden: Former Gov. [Eliot] Spitzer [of Spitzer Enterprises] is a client of ours. And Toll Brothers, which is a major condo developer, they’ve got to take a better look now because they don’t have 421a on [condo] projects going forward.

Your firm worked on Spitzer Enterprises’ new three-building rental complex at 420 Kent Avenue. Eran Chen of ODA, who designed the project, told us he had a very tight turnaround on that project so it would be eligible for 421a.

Schein: The program was going to end, and we didn’t know if there was going to be a new program.

Seiden: It’s funny, because [Spitzer] recently called about another project that he’s thinking about buying, which I can’t mention. We did the original work on that, and it had vested under the old 421a. So he asks, “How do you know that?” I said, “We’ve got the photos, we’ve got the cement tests, we’ve got everything.” He says, “You guys really know what you’re doing.” So we have that reputation of being pretty diligent.

You mentioned some of the key differences in the new Affordable New York Housing Program that replaced 421a, such as how it doesn’t apply to condos and how developers have to wait until after a project is completed to receive the tax abatement. How else is the new law different?

Schein: The obligations are more or less depending on the type of building you’re doing. High-rent, market-rate apartments are not subject to rent stabilization, which was a big deal under 421a. On the other hand, if you’re doing a building that’s more than 300 units, you have to pay prevailing wages for construction, which is a major cost.

Seiden: You have a lot of 299-unit buildings.

Schein: Overall, the program is liked by developers; it does provide a benefit. The oddity is that the city gives with one hand and takes away with the other. If you had a fair tax program to begin with, they wouldn’t need us. But because of the high taxes, you can’t build rental housing without it.

Speaking of which, Mayor de Blasio recently announced a new property tax reform advisory commission, which just had its first meeting in July. What are the biggest flaws in the city’s property tax code, and how can they be reformed?

Schein: Again, it’s very political. Some people say the co-op and condo owners aren’t paying enough, which [those owners] would disagree with. The class that’s really under-assessed is private homes—one- to three-family homes, which pay a small fraction of what everybody else pays. You could buy a $4 million brownstone in Brooklyn and have taxes that are like $10,000 a year. You could have a 1,000-square-foot, two-bedroom apartment in Manhattan and pay the same tax as that brownstone. It’s off by that much.

Seiden: There’s a hidden secret in all of this, which is that the city’s borrowing capacity is based upon the taxable assessed value of real estate. The way they support all of the city’s systems is that they borrow—and the higher the [property tax] assessments, the better their bonding capabilities are. And no one ever speaks about that. If you reduce the assessed value cap, then the city’s bonding capabilities would be a lot less. It’s a very progressive administration that likes to spend a lot of money, and the money comes from taxes.

Finally, I’d love your take on the de Blasio administration’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing initiative, which is a vital component of the mayor’s affordable housing goals. How has it been received by developers, and is it having the desired effect of boosting the city’s affordable housing stock?

Schein: Mandatory Inclusionary Housing was a big deal. The city was very concerned that it be legal and constitutional, because now you’re telling somebody they have to do something—it’s not voluntary. One of the integral parts of the program was that [the city] just assumed that market-rate developers would be getting 421a to make it work, because if you’re going to have 25 to 30 percent of the building at lower incomes, you have to get a tax break.

Unfortunately, it came out when 421a was dead. The first [rezoning] was in East New York, [Brooklyn], which was probably not the best place to start because it’s a challenged area, and there was never a whole lot of development going on in East New York to begin with. And right now, I’m not aware of too much market-rate development going on even since [the rezoning] happened—it’s almost all affordable.

My own view was that the statute probably was unconstitutional and it probably violated the Urstadt law, a state law that prevented the city from dictating its own rent caps. It works under 421a or voluntary inclusionary, because if you want the benefit, you agree to affordable rents. But if the city is telling you that you have to have affordable rents, that probably violates the Urstadt law. But nobody’s challenged it, so it’s legal as long as nobody says it’s not.

Developers are dealing with it. I thought there’d be less acceptance of it. But mainly where it’s coming into play is in rezonings, where if you want to convert a manufacturing site to residential, and you get a big increase in the floor area, it’s worthwhile. I would expect over time that one neighborhood after another will become [rezoned for] mandatory inclusionary, and we’ll see how that affects development. But developers are incredibly resilient here—there’s nothing you can do that seems to stop them. They’re going to build.