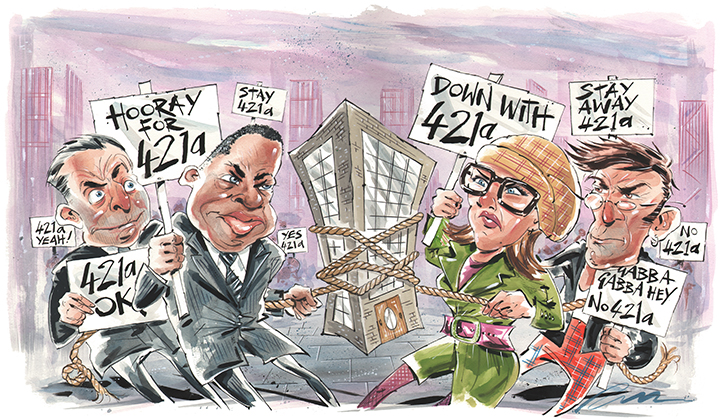

Lapsed 421a Break Leaves City’s Real Estate Community Scrambling to Get the Program Back

By Tobias Salinger January 20, 2016 10:30 am

reprints

Deadline Day

On Friday afternoon, hours before New York City’s largest and most controversial tax break was set to end at midnight, some were acting like the city was bracing for a nuclear blast.

Leaders of the Real Estate Board of New York and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York didn’t even wait until the official deadline before they conceded the 421a tax program was over.

REBNY and the construction workers unions needed to reach a deal on construction wages to preserve the 44-year-old, $1-billion-a-year property tax exemption. All last week, real estate pros were panicking that the once-unthinkable was happening right before their eyes.

Indeed, how could a four-year extension of 421a passed in Albany and championed by Mayor Bill de Blasio get tossed in the trash? The mayor professed hope until the end, telling reporters last Monday, “There’s time on the clock.” But the prospects looked grim. Anonymous persons close to the REBNY-Building Trades talks had been whispering gloom for months.

“It ain’t happening,” one insider told Politico New York Tuesday night. And that voice proved prophetic.

The 421a program is referred to by both its backers and its critics as a developers’ tax break. The property tax exemption of up to 25 years goes to residential builders and owners in exchange for affordable housing in certain parts of the city, and the new law would have expanded that requirement to all new residential projects citywide.

Yet the same new law pronounced itself void if REBNY and the unions didn’t find common ground on prevailing wage rules for 421a-aided projects. The tax break, which usually gets extended every four years, expired in 2010. But state lawmakers reinstated it for four years six months later (after renewal was set to start in 2011, it got a brief extension in June, but only through 2015). And almost immediately after last Friday’s talks blew up, the only question for the real estate community was how to get it back.

Real estate leaders, the abatement’s many vocal opponents and elected officials on both sides of the issue now must brace for the impact of another lapse. The 421a tax break involves the city’s history, its politics and its economy. The tax break started in the 1970s at a time when some worried whether anyone would want to build new housing in the city. The current impasse between REBNY and the Building Trades Council comes with some concerned the demand for new housing in the city will push everyone but the very wealthy out.

‘Unless you get New York developers to build more and more buildings, you’ll have a diminished housing stock. So I think we need to get New York developers to build more and more apartment buildings.’—Martin Heistein of Belkin, Burden, Wenig & Goldman

Many tenant advocates want 421a either gone or significantly altered. Both Mr. de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo have promoted the law passed in June (subject to REBNY and the Building Trade’s agreement) as a big change in the tax break often derided as a giveaway to developers. The real estate community supported the new law, only to see its hopes dashed. Now the onus is on the industry to make the case for bringing 421a back.

“I know there was a period of time when 421a was up in the air, and construction came to a near halt,” said Martin Heistein, a Belkin, Burden, Wenig & Goldman partner who worked seven years as general counsel to the residential landlord advocacy group the Rent Stabilization Association. “Unless you get New York developers to build more and more buildings, you’ll have a diminished housing stock. So I think we need to get New York developers to build more and more apartment buildings.”

He added, “The mantra is: ‘More housing helps the people.’ ”

Lies, Damn Lies and Statistics

No one disputes that 421a has produced housing all over the city. The law requires setting aside 20 percent of a building’s units as affordable to receive the tax break and the owners of over 168,000 units of housing got the break last year. (Friday’s missed deadline won’t affect properties already receiving the break, or those slated to receive it.)

The debate revolves around whether the program, which cost the city over $1.1 billion in forgone taxes in fiscal year 2015, ending June 30, has spurred enough affordable units.

The figures become murky when it comes to the number of affordable units produced through 421a. Housing advocates at the local nonprofit Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD) estimated in a report last January that only 12,700 of the 153,000 units helped by 421a in fiscal 2013—about 8 percent—were affordable. The 421a program’s $1 billion price tag leads to about 1,000 new affordable units per year, which is “not a very good deal” and “couldn’t possibly be defended as a housing program,” Tom Waters of the Community Service Society said last year at a City Council oversight hearing.

Yet many city officials and real estate leaders who defend 421a trot out different numbers. The tax break supported 7,600 new affordable units out of a total 42,000 new units—18 percent of the total—between 2009 and 2014, officials at the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which administers the 421a tax breaks, told Commercial Observer. The city will lose some 18,000 affordable or below-market units over the next four years without 421a, REBNY warned Friday.

Concerns over transparency prompted the Municipal Art Society to publish a map showing every building that gets 421a with the amount of the tax break and the number of affordable units. “The 421a is part of a myriad of initiatives and rules that we’ve accumulated over decades,” said Mary Rowe, the executive vice president of MAS. “We’re not trying to throw the baby out with the bathwater here. It’s just saying, ‘Make these constructive changes.’”

MAS also tracked the history of 421a, starting with its creation in 1971. Then-Mayor John Lindsay, conscious of a declining population and real estate investment, asked state lawmakers for tax incentives for residential developments. Like Mr. de Blasio more than four decades later, he received much of what he asked for from the state, at least with respect to the 421a.

Mark Willis, a former HPD official who is a senior research fellow at NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, looked to the program’s history to describe what could happen without 421a. He and two colleagues found in a November report that the loss of 421a could force land values and housing production down in low-income areas like Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn.

“In 1971, there wasn’t much of any construction going on at all,” Mr. Willis said. “You could draw a parallel between then and some of the neighborhoods today where rents would be insufficient to justify construction without the 421a tax abatement.”

Such construction didn’t entail an affordability component anywhere in the city until 1985. This changed after Mr. Koch’s attempt to block Trump Tower’s $50 million tax break. The New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, ruled in favor of Trump Tower developer Donald Trump’s right to receive 421a.

“One last element helped make the Trump Tower deal a huge home run,” the future GOP candidate later wrote in The Art of the Deal, “and that was something called a 421a tax exemption.”

Yet the popular outcry stoked by Mr. Koch prompted Albany legislators to create an affordability requirement for Manhattan projects between 14th and 96th Streets.

Upper West Side Story

Councilwoman Helen Rosenthal brought up a property at the 421a oversight hearing last January that still bears Mr. Trump’s name but changed from his hands long ago. (Disclosure: Donald Trump is the father-in-law of CO’s publisher, Jared Kushner.) Around 2,500 affordable units could turn market rate over the next five years as the temporary tax breaks expire on the Upper West Side, which is marked by Trump Place on part of its westernmost edge, said Ms. Rosenthal.

“Fundamentally, my problem is the entire notion that the affordability would expire at any time at all,” she told CO. “My ask of the administration is to find ways to keep these units in affordability forever.”

Ms. Rosenthal and legions of critics have also protested the 421a tax breaks enjoyed by multimillion-dollar condo owners at Extell Development Company’s One57. Yet 421a opponents forget the impact new construction has had on jobs, said Robert Knakal, the chairman of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield.

“It also adds tremendous tax revenue to the city. Yes, there will be some wealthy people receiving tax benefits, but those tax benefits will be temporary,” Mr. Knakal said. “And when those tax benefits expire, the tax revenue for a single apartment can be more than it was for the entire tax lot.”

Ms. Rosenthal’s district is a set piece all its own for the complexity surrounding the 421a debate. Chicago-based Equity Residential, which now owns three high-rise buildings at Trump Place, manages 174 affordable units at 140 and 180 Riverside Boulevard; 421a cuts Equity’s taxes by more than $40 million at 140 Riverside Boulevard and over $19 million at 180 Riverside Boulevard, according to city Department of Finance records.

‘Fundamentally, my problem is the entire notion that the affordability would expire at any time at all. My ask of the administration is to find ways to keep these units in affordability forever.’—Councilwoman Helen Rosenthal

Yet the abatement runs out in 2024 at 140 Riverside Boulevard and in 2019 at 180 Riverside Boulevard. Average asking prices for market-rate units at the 40-story building at 180 Riverside Boulevard, which overlooks the Hudson River and sits next to parks, run around $4,300 per month, according to StreetEasy.

A representative for Equity didn’t respond to questions about whether the affordable units would remain once the tax breaks expire.

Four blocks south, the Brodsky Organization provides 200 affordable units out of 1,009 overall at the West End Towers for $565 to $735 per month, according to the company. The two-building property’s $12.4 million tax break will end in June. But Brodsky executives plan to keep the affordable units and add 50 middle-income units on site, the company said in a statement to CO.

“We feel that it is a beneficial program that preserves affordable housing in quality buildings situated in New York City’s premier neighborhoods,” Mr. Brodsky said of the tax abatement program.

A Lousy Reputation

The controversies surrounding 421a have led to a variety of bad names for the tax break.

Investigative news outlet ProPublica called it part of “The Rent Racket” in a series about property owners who skirt the terms of the tax break. The Real Affordability for All campaign, a grassroots group of tenant activists, referred to 421a as the “LUXURIOU$ LOOPHOLE,” in an April 2014 report.

City Council members called 421a a “billionaire boondoggle” at the City Council oversight hearing last year. Williamsburg City Councilman Antonio Reynoso blamed a displacement of 14,000 Latinos in the area’s population over the last 12 years on the pace of development aided by the tax break. And Washington Heights and Inwood Councilman Ydanis Rodríguez asked Department of Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Vicki Been how anyone could trust that the program works when 20 developers in his district received the tax break without creating any affordable units.

“There are lots of criticisms of this program, there are lots. And I want to make clear: it’s not a program that I asked for. It’s not a program that, you know, was on this administration’s watch,” Ms. Been said. “It’s a program that was, you know, legislated from Albany, obviously with the city’s involvement. So I’m not here to defend the program. I’m here to ask how could it be made better.”

More Than Half a Loaf

Mr. de Blasio unveiled his administration’s answer in May, a month before the law was set to expire. The resulting law drew support from REBNY and united the mayor with the real estate community in a bid to change 421a, but keep it alive.

The state law that was passed on June 25 and signed by Mr. Cuomo would have strengthened 421a’s affordability requirement along the lines Mr. de Blasio proposed. The law would have gotten rid of what is called the “geographic exclusion area”—an area where affordable units were required—by making the whole city subject to the requirements. It also would have extended developers’ tax breaks to as long as 35 years in exchange for setting aside up to 30 percent of units for affordable housing onsite. And it would have ended the tax breaks for Manhattan condos.

Real estate leaders lined up behind the mayor, both in their words of support for his plan and in financial contributions. Real estate executives gave over $800,000 in the first half of 2015 to Campaign for One New York, a political organization linked to the mayor and operating outside of the city’s campaign finance laws, The Wall Street Journal reported.

REBNY’s members backed Mr. de Blasio’s 421a plan from the day he announced it. The mayor “now understands the importance of working with the real estate community instead of, I won’t say ‘attacking,’ but criticizing the real estate community,” said Mr. Heistein, the former Rent Stabilization Association counsel. And, for their part, real estate leaders had agreed to meet Mr. de Blasio halfway, he said.

“The obligation to set aside additional percentages of units for low- and moderate-income residents was a big change,” Mr. Heistein said. “That’s something that property owners realized has changed in New York City.”

Mr. Cuomo helped add the hitch in the law—a shutdown of 421a if REBNY and the Building Trades didn’t reach an agreement on prevailing wages. Yet real estate leaders joined with the mayor in pushing for the new law to go into effect in 2016. The law required 421a to continue under its prior form for the rest of 2015. Yet REBNY and Building Trades would have to find common ground on wages to set the new rules in motion. Both REBNY President John Banks and Chairman Rob Speyer spoke optimistically in an interview with CO in late December.

“Affordable housing is a crisis issue for the city. We have a mayor who’s put it at the very top of his policy agenda. And as an industry, we’re committed to doing everything we can to help him to advance that agenda,” said Mr. Speyer, the CEO of Tishman Speyer. “The challenge with the 421a legislation is significant, but that’s not going to stop us from putting every effort forth to work with the unions to resolve it.”

Things Fall Apart

The two sides couldn’t make a deal, though. The news on Friday night followed a week marked by questions about how much extra a prevailing wage might add to construction costs.

The city’s Independent Budget Office revealed its estimate last Monday that the cost of Mr. de Blasio’s proposal to build 80,000 new affordable units could jump by $2.8 billion if developers paid construction workers the agreed-upon salary. Such rates run much higher than median industry wages, and the prevailing wage rules also cover health insurance premiums, retirement contributions, life insurance and paid leave.

Building Trades President Gary LaBarbera responded with a statement pointing out that the report didn’t factor in “the massive tax breaks developers receive under the 421a program.”

The episode foreshadowed the breakdown in talks between the unions and REBNY at the end of the week. It also revealed how the disagreement over costs had doomed the talks.

“Unfortunately, despite a good faith effort by all parties, REBNY and the Building Trades were unable to come to a final agreement on the renewal of a 421a program that would provide good wages to construction workers across the city,” Mr. LaBarbera said in a statement.

Mr. Banks released a statement voicing REBNY’s concern that the loss of 421a will make all residential developments that aren’t condos non-viable. (Condos have been covered by 421a for all 44 years—but the law would have ended the abatement for condos in Manhattan if REBNY and the unions reached a deal. Condos in the outer boroughs with fewer than 35 units would have still been eligible under the new law.)

“New York is a city of renters and one that continues to grow,” Mr. Banks said. “Without a program like 421a, one can’t build multifamily rental housing with a significant below-market, or affordable, component on a scale necessary to address the city’s needs.”

Mr. de Blasio joined both in promising to work toward a future agreement, even though he called the failure to put the new law into effect “deeply disappointing” in a statement Saturday.

“We are facing an unprecedented crisis of affordable housing, and we must employ every tool at our disposal to confront it,” Mr. de Blasio lamented.

Picking Up the Pieces

REBNY and its members had been imploring against any 421a lapse long before even the first deadline in June. Industry leaders predicted land prices and new housing starts will fall without the tax break. Yet no one can say for sure when, or if, the tax exemption might return.

An extended absence of 421a could cause a “negative feedback loop within the broader economy,” Mr. Knakal said. “It would be a market for a period of years, probably two, three or four years, where nothing is going to sell. That means you may not get new product delivered to the market for six or seven years.”

Mr. de Blasio said, “The death of development is an overstatement by any definition,” at a press conference last Monday before the program expired. The mayor’s office announced that day that the city has financed over 40,000 new and preserved affordable apartment units in Mr. de Blasio’s first two years in office.

“We’ve been down this road before,” he said of the looming 421a deadline. “There have been times when it lapsed in the past, and then there was oftentimes action to resolve the issue after the fact.”

If history is any judge, then the 421a will come back again someday. It may take a different form or a prevailing wage agreement as part of passing the law. Those watching closely don’t expect tenants’ need for cheap housing, developers’ need for an incentive or the city’s need to adapt to new times to expire any time soon. No one really knows what will happen in the interim.

“You can get preoccupied with those kinds of conjectural things and I don’t know how productive it is,” Ms. Rowe said. “We’re a sophisticated city and we have sophisticated problems and we need sophisticated solutions.”

With additional reporting provided by Terence Cullen.