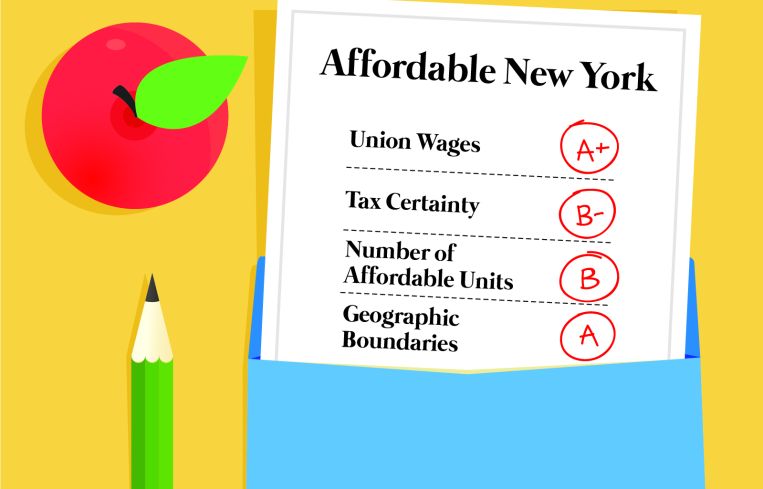

Checking in on Affordable New York, One Year Later

By Rebecca Baird-Remba June 13, 2018 11:45 am

reprints

When the 421a tax exemption collapsed for 16 months, New York’s real estate world flipped out. The Durst Organization, for example, halted construction on one of the biggest affordable projects in the city, Halletts Point in Queens, and new building permits took a dive. But now it’s been just over a year since the new 421a program—dubbed Affordable New York—was signed into law by Gov. Andrew Cuomo, and things seem to be going well, albeit slowly.

“Construction as far as I can tell has picked up the pace,” said Jason Hershkowitz, a partner and land use lawyer at Seiden & Schein. “We’re certainly seeing more projects get off the ground.”

The revamped 421a tax break comes with more rules than the old one, which dated back to the 1971 and was designed to incentivize development in a downtrodden New York City rather than create affordable housing. And developers can only apply for the new Affordable New York exemption when their buildings are complete. Unlike the old 421a, developers now have to pay for their property taxes during construction.

But if owners do secure 421a once the building is complete, they get a retroactive tax benefit that covers the taxes paid during the construction period. Under the old version of the tax break, builders could nail down an agreement that would exempt them from property taxes for the next 10 to 25 years once they had laid foundations for a new development.

Financial institutions and lenders are still adjusting to the later 421a certification timeline.

“The timing of the process is causing a little uncertainty in the lending world because they’re used to doing this at the beginning of construction, but the requirements are pretty clear,” said Jennifer Dickson, a planning and development specialist at Herrick Feinstein.

However, the delayed schedule of the new Affordable New York program means that so far, the city has only awarded the tax break to four developments, according to a spokesman for the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). Another 142 buildings are currently wending their way through the agency’s lengthy review process. Citywide, there are 72,390 properties with the old 421a tax break in place, according to the city’s annual tax expenditure report. Together, the old and new programs cost the city $1.43 billion over the past year.

Despite the change in timing with the new tax exemption, Dickson said that developers appreciate the consistency of the new program’s rules, which require them to set aside at least a quarter of the units in a new building as below-market housing. The old 421a law only required developers to build affordable housing if a development was in the “geographic exclusion area,” or GEA, which essentially encompassed Manhattan below 96th Street and gentrified areas of Brooklyn and Queens. But the boundaries of the GEA would shift every few years as legislators modified the program to include increasingly expensive areas of the outer boroughs, sparking confusion among Brooklyn and Queens developers who wanted to score the tax break.

Then there are the controversial wage floors built into Affordable New York, which were the product of a long negotiation between the building trades unions and the Real Estate Board of New York. (As a comment, a REBNY spokesman sent along an editorial by the group’s president, John Banks, that highlighted New York City’s booming housing construction numbers over the past few years.) Under the new version of the tax break, developers of projects with 300 units or more have to pay construction workers wages of $45 to $60 an hour, depending on whether the building is in Manhattan or the outer boroughs. In exchange, they get a 35-year property tax exemption. However, the city housing agency doesn’t certify that the wage requirements have been met. Instead, contractors must submit their payroll records to an independent monitor—usually an accountant or lawyer—who must then get the approval of the city Comptroller’s Office. However, HPD can’t deny a 421a certificate to a developer if he or she fails to meet the minimum wage requirements, according to the agency’s website. But a contractor does have to repay workers for any wage shortfalls, with interest.

While lawyers were concerned about the certification process for the new program’s wage requirements when they first went into effect a year ago, now they say HPD has actually made its 421a review process more efficient.

“The review period is actually shorter [than the old program],” Hershkowitz said.

The reworked tax exemption also dramatically limited the options for condo builders. In order for a condo building to qualify, each apartment must have an average assessed value of no more than $65,000. That means only relatively cheap apartments pass muster under the new program. The more pressing question is whether the missing tax break will particularly hurt buyers and builders of mid-priced condos in the outer boroughs.

“The fact that the home ownership option is so limited does seem to have an impact on condo projects,” Dickson said. “I think that at certain price points it may be something that condominium [owners] would have expected more than at the higher price points.”