Lodge Podge: Masonic Temples in LA Are Ripe for Reuse

The world’s first and largest fraternal organization has some excellent real estate ... provided you can get past the Masonic Properties Committee

By Alison Stateman May 14, 2018 11:00 am

reprints

Adaptive reuse has been around a long time—but perhaps not as long as the “world’s first and largest fraternal organization,” namely, the Freemasons, who have some pretty sweet real estate that can be transformed into something a little more in keeping with Los Angeles in 2018 (i.e., an office or a bar).

Which is exactly what is happening.

Last November, The Lodge Room, a small theater and restaurant mixed-use venture, opened in the former Highland Park Masonic Temple. This followed on the heels of the Marciano Art Foundation launch last spring within a renovated Scottish Rite Masonic Temple at 4373 Wilshire Boulevard. Interspersed among the Guess founders’ private art collection are ornate relics left behind from the fraternal order, including huge stage backdrops and wigs from the temple’s theater.

Before that, CBRE turned to a renovated once-unoccupied temple in Glendale into their northeast regional office, which, with its soaring 37-foot ceilings and sunlit-interior showcases a prime example of adaptive reuse.

But altering such historic structures is not as simple as getting permits or hiring a commercial real estate broker. All property improvements of $25,000 or more must be pre-approved by the Masonic Properties Committee. In addition, if lodges are recognized as designated historic landmarks, as many are, there are strict guidelines about alterations. That hasn’t stopped folks from eyeing and transforming historic lodges into present-day gathering places of the office and cultural variety.

When David Josker, the managing director of the Los Angeles north region for CBRE, was tasked with finding a new location for the firm’s northeast operations, he set out seeking a property different from their office in a traditional high-rise building near Universal Studios in the San Fernando Valley.

The path to selecting and turning a historic masonic lodge into one of the firm’s most talked about offices at 234 South Brand Boulevard in Glendale, was not a simple one.

Two years before lease expiration at 111 Universal Hollywood Drive at the end of 2015, the firm set up a site advisory committee and began the hunt for a new location within 10 miles of the existing location.

“We made the decision that we were likely not going to stay in our existing space and this was an opportunity to really transform from a geography and from an office space standpoint how and where we were operating,” Josker recalled. “The space that we came from was very traditional office space, but it had very few amenities around it so we had to basically get in our cars and drive to go to anything.”

The move coincided with an overall corporate decision to change how the firm operated, moving away from the concept of a traditional office with cubicles and set office spaces to a more free-flowing model. “We changed to a Workplace360 concept, which is more of a free-addressing, [no assigned desks] paperless environment, focusing on more of an open workspace [cloud storage] and activation of those spaces and around collaboration and technology,” Josker said, adding that the first CBRE office to adopt the model in the U.S. was the firm’s Downtown Los Angeles headquarters at 400 South Hope Street in 2013.

The former masonic lodge in Glendale, located across from the Americana at Brand was one of the initial and top spots he and the committee team viewed. Originally completed in 1929 by Arthur G. Lindley, who built several Methodist churches throughout Southern California, it had been without a permanent tenant for decades.

“When we walked in, we really fell in love with it and the allure and the uniqueness of the building,” he said. “It had such a cool, architectural quality to it. The building itself is 90 years old and it was built by hand by 427 masons. We immediately saw the potential.”

However, two challenges stood in the way. The location was one of the farthest sites they had considered and it required extensive renovation. (There was no elevator and limited electrical, plumbing and HBAC systems, at the nine-story building.)

In response, the CBRE team took the property off their list and went on to other options over the next 13 months, whittling down the choices to two locations in Burbank. That’s when they received an unsolicited offer from Caruso Affiliated, headed by Rick Caruso, the billionaire mega-developer behind the Grove and Americana at Brand malls, which had acquired the property from Frank De Pietro and Sons since they first saw it.

Caruso’s group sent over a hardbound book with the CBRE logo engraved with a list of the amenities, from parking to specialized concierge services as tenants in the space. In response, the committee added the site back on the short list and ultimately chose to take four floors of the 50,000–square foot property, where they are currently the sole tenants.

Caruso fully renovated the building within the eight months between when the lease was signed and CBRE staff moved in on Jan. 4, 2016. This included doing away with small windows that barely let any sunlight in on two sides of the building, quirks belying the secretive nature and architecture of the masons.

The result, a 24,000-square-foot Gensler-designed space (with input from CBRE’s workplace strategy group) seems almost a temple to both modern architectural design and workplace practices, particularly on the firm’s seventh and eighth floors. The top floor is two-stories tall with stadium-seating area in the vaulted cathedral-trussed penthouse, with exposed concrete and structural steel elements from the original building.

“Caruso punched 18 windows into the sides—actually nine on each [of the longer] sides of the building—and [they were] 10-feet wide by 20-feet-high because masonic temples don’t historically have a lot of windows in them,” Josker said.

Caruso did not return calls for details, including the cost of renovating the temple. CBRE also declined comment.

Sometimes, former temples are redesigned to remain a social gathering place, but for a new generation. Think less velvet fez and more man-bun. When the former Highland Park Masonic Temple came on the market in 2015, Hugh Horne saw an opportunity to turn the underutilized landmark into a neighborhood hub for local artists, musicians and cocktail and food enthusiasts. Private partnership and investors purchased the 19,000-square-foot building at the corner of North Avenue and South Figueroa Street for $4.8 million that July and enlisted Design, Bitches to help modernize the space.

“It came on the market as basically a mixed-use building with ground-floor retail and then these two banquet halls on the second floor, which were used sparingly for local event rentals,” Horne said. “We just thought, we love the neighborhood, we love the architecture and we just really believe in this corridor of Figueroa [Street]. The building had beautiful bones, beautiful, historic features. This was the crown jewel of a building and so when it came on the market, it was something we were very interested in.”

Horne kept all the retail tenants on the ground floor, including Delicia Bakery, whose owner sold him the property, Good Girl Dinette and Avalon Vintage. He then had the space permitted to allow a restaurant and small theater on the 8,000-square-foot second floor to give local musicians and performers a place to do shows.

“You have so many creative artists and musicians that live in Highland Park, Eagle Rock and the Eastside of Los Angeles, yet they don’t really have a proper venue to play at. They have to go to Hollywood. Folks in the music industry recognized an opportunity to do shows [here] and we thought that is the highest and best use, a combination of live performance and events,” he said. “So, nothing was lost—we still have the ability to have events—we just gained the opportunity to have live performance.”

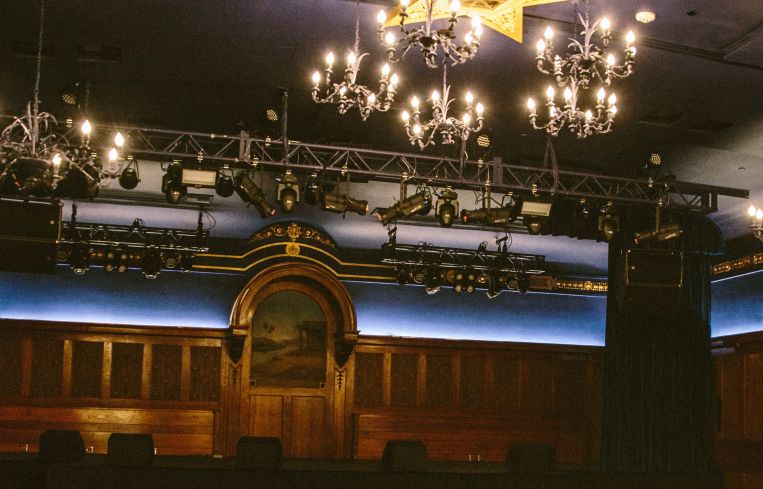

In-house talent buyer Raghav Desai books acts at the performance space, which, at approximately 3,000 square feet, can accommodate around 400 people. It opened for live events last November. Recent performances include a sold-out set by comedian Dave Chappelle, Hockey Dads and Company of Thieves.

Horne set about upgrading the temple infrastructure by installing an elevator that was ADA-compliant, a commercial kitchen, smoke alarms and other updated fire protection equipment.

From a design standpoint, however, he focused on preserving and restoring some of the period details—including Egyptian motifs and murals, which Horne said after years of exposure to smoke and gatherings needed to be “brightened up and brought back to life.”

He paid homage to the space’s former members by adding large-format checkered linoleum to the stairway, as the pattern is heavily used in masonic design.

They kept the original wallpaper in some of the restrooms and parlor rooms that felt contemporary, while doing away from some of the outdated beige and pastel colors used when the hall was last painted in the 1980s, replacing it with a blue-green color that darkens as you move further into the space.

“Our designers are really excellent with colors. They created this real story with the color. They replaced the’80s pastels with a modern blue-green color that gives a little bit of contemporary design into an old building,” he said. “They are really known with work with color [and we were] not afraid to go with color because it’s a place of art and creativity and expression.”

Aside from adding a bar in the performance space and refinishing the floors, they kept the “really beautiful woodwork” and chandeliers dating back decades.

For the remaining space, he created a restaurant dubbed called Checker Hall in a redesigned 2,000-square-foot space and a lobby bar where patrons can grab a cocktail before or after shows. In a nod to the temple’s style, the restaurant offers Mediterranean-inspired cuisine. It also features a variety of seating, from barstools to booths, as well as formal dining and cocktail-seating for patrons looking for a quick bite and drink before a show.

“It’s a large room, quite tall and was painted beige. It felt a little like a cafeteria, a little blank so our designers created the bar to be in the middle of the room to make it more intimate,” he said.

In the process of renovating, he said was delighted to find some architectural surprises, underscoring the style of the insular, though philanthropically minded masons.

“There’s a couple of panels in the wall that look like panels, but they’re secret doors,” Horne said, describing a hidden door in the corner of the room that now serves as an entrance from the green room to the stage and another found on a wood panel decorated with an old landscape mural.

“We didn’t find secret floors or secret rooms,” said Horne, sounding a bit disappointed. “But there’s some really unique architectural features and secretive details that we kept in place and sort of brought back to life. They’re really cool.”

Subscribe to CO’s Los Angeles Weekly Newsletter for more stories like this at commercialobserver.com/subscribe