Fannie Mae’s Jeffery Hayward Talks Affordable Housing, Millennials and Zoning

By Matt Grossman April 11, 2018 9:45 am

reprints

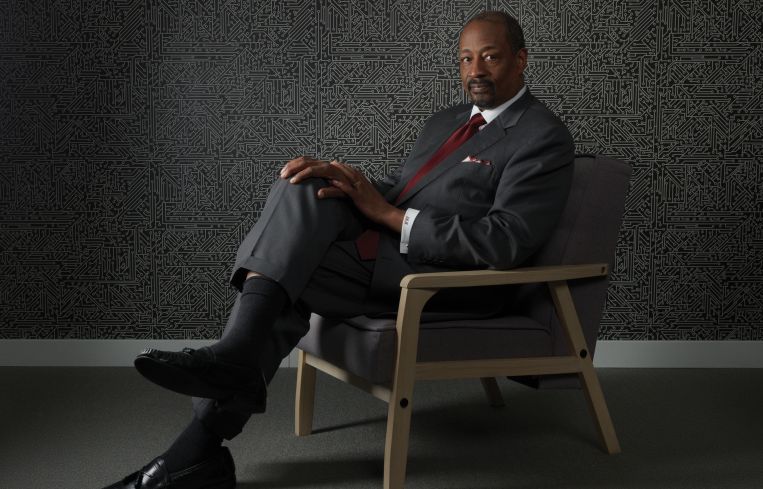

Few organizations have more influence over where Americans live than Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae—the government-sponsored entities (GSEs) that secure residential mortgages. And few leaders at those institutions are more influential than Jeffery Hayward, the 30-year Fannie Mae veteran who now heads its multifamily lending business. As we celebrated last week in our tribute to Hayward on our Power 50 list (he was No. 14), Fannie Mae recorded its best year ever in 2017, turning around $67 billion in financing and issuing nearly as much in commercial mortgage-backed securities.

But Hayward, a graduate of Pennsylvania’s Widener University, is much more interested in his agency’s path-breaking work in two public-oriented missions: its longstanding commitment to promoting affordable housing, and the newer incentives it backs for developers to consider energy and water efficiency in the apartments they build and manage.

The Fannie Mae executive, 61, lives with his wife in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Bethesda, just across the Maryland state line. The couple has two daughters, the older a pastry chef and the younger a college student. But even a chat about the lending executive’s home life comes full circle back to the history of American housing and demographics.

In just the last few years, Hayward—who had never played an instrument before—learned the electric bass by joining a blues band, a musical style that he quickly fell in love with. He noted that the blues evolved in the early to mid-20th century as masses of southern African-Americans migrated north to cities like Chicago, Philadelphia and Memphis that became laboratories for artists forging a new musical landscape. And just as the new sounds they created inform pop music even today, the communities that flourished during that era continue to shape the country’s housing patterns.

The blues is an intellectual riddle to Hayward. “It’s great mental exercise,” he said. “How do you play all these notes?”

With multifamily lending, on the other hand, he seems to have it all figured out.

Commercial Observer: A big part of your mission is promoting affordable housing. What’s most important for developers to know about your work in that area?

Jeffery Hayward: In the affordable space—and I’m talking about below 80 percent area median income—we did $6 billion of business [in 2017]. To me, what’s important though is that we did this across states. We did a lot of business in the middle of the country. We’re not just building affordable in places like Hoboken, [N.J.] or out in Sacramento, [Calif.] We also did it in Oshkosh, [Wis.] That means the full effect of what we do every day is felt by the average American citizen. Six billion dollars is a great number, but the bigger number in my view is how many states were affected.

How challenging is it for developers to turn a profit on affordable housing? Is that a big roadblock in getting more built?

For developers, it costs you as much to acquire land no matter what. You start out in the hole, because land is the same whether you’re building high or low in the market. And the increasing costs of labor [are pervasive]. Your margins in an affordable project, generally, will be less than any other product. In the lending business, I would say that banks do just fine on affordable lending. The way we do business, we make enough [profit] on our affordable lending. It’s not like it’s a loss leader. Do we make as much as something that’s market rate? No, but my view is that when you mix it all together, it’s the right thing to do.

With aging demographics in mind, how has the role of multifamily in the broader housing landscape changed?

When you talk about institutional multifamily, the [lending] standards are better [than they used to be], meaning how these buildings are financed is better. Owners are more sophisticated. It used to be a family would own and pass an apartment building down through generations. That’s changed a lot. You have a lot of institutional private equity firms that own apartment buildings, and real estate investment trusts that own apartment buildings. The ownership is much more sophisticated.

Does institutional ownership translate into improved credit quality?

I think the simple is answer is yes. When you have institutional ownership and they own a lot of apartments, that enables them to keep their costs at a reasonable level, because they have scale. There are certainly families that do a terrific job of owning properties, particularly here in New York. [Some families] have owned properties for years and years, and do a good job.

How do differences in housing preferences among millennials and baby boomers, for instance, affect the market?

For the millennials, an apartment building is a place they might want to live. For a lot of older Americans, a single-family house is where they want to live. The changes in the rental market in general [have been that] after the financial crisis, more Americans rent single-family houses than rent apartments. Most people don’t know that. The rental business has changed in America. Its ownership structure has changed. There are challenges for all of us to figure out how to continue to finance it in the right way.

How would you characterize the environment that a multifamily developer encounters when trying to find financing for a new project?

Apartment owners have lots of choices in terms of capital sources. If you’re developing a Class-A building, most of that business is with insurance companies. But the issue in multifamily is not the financing. The issue is supply. If you talk to owners of apartments, they’ll tell you, that buying an apartment building is difficult because the price is high. It’s high because the demand for apartments is high, because of the millennials. In the [market for apartments that are affordable to those making less than the area median income], there isn’t enough supply for renters. There are so many renters and so few apartments because of how much it costs to live, how expensive land is, how zoning is. And I think zoning is probably the biggest issue in a lot of jurisdictions.

How do zoning constraints influence the cost of living?

In a given jurisdiction, they might say, you can’t have more than X [density] in this jurisdiction. Here’s what that does: It crowds out affordable housing. There’s plenty of financing for the developers—the GSEs play a very important role in that. But the bigger issue is supply. Now, we can start helping figure out how to solve the supply problem but we can’t do it alone. That’s really the issue.

How pervasive are these zoning problems?

It’s everywhere. Zoning in every part of the country is the biggest enemy of affordable housing. I guess it’s not an absolute. There are places like Houston, for instance, where they don’t have zoning restrictions. Things can be built. But in San Francisco, New York, and Philadelphia, zoning restrictions really do matter. There’s a lot of this—”not in my backyard.” [People think,] “I want those people to have housing, but I don’t want to have those people live around me.”

Any developers who studied the demographics would have seen the millennials coming for years. Shouldn’t they have foreseen a multifamily shortage, and gotten ahead of the curve?

First, during the housing crisis, no apartment buildings were built. Working against the millennials was suppressed production for the better part of three to four years. Second, I think zoning in local municipalities only got worse, meaning that everybody didn’t want affordable housing in their backyard, and they made rules that made it very difficult to build such housing. Third, there’s a labor shortage. A lot of the labor either went to other professions or in other cases, there were people from other countries who went back to their country of origin [during the financial crisis]. You have a shortage of plumbers, carpenters and electricians. The last thing I would say is particularly in cities, the price of the land is a problem.

Now that equities have shown some weakness, do financiers have concerns about this stage of the business cycle?

Lenders, I think, are feeling good about the business because the demographics are so strong. The things you usually see when a cycle ends, you’re not seeing them. For instance, people are not stretching to make loans they should not make. That would be a sign you’re at the end of it. And rent continues to rise. The business works when rents rise and their incomes are rising. Incomes have been stretched a little bit. But as long as rents are stable and rising, the lending business, which relies on repayment based on rent collection, is fine.

Financing eco-friendly improvements has been an incredible success story at Fannie Mae. How did that get started?

We started some years ago our green financing business. It was an experiment. We worked with [the Environmental Protection Agency’s energy-savings program] Energy Star. We worked with the Department of Energy—we worked with all these people to figure out how to bring energy efficiency into mortgage financing. So we started small. We did $3 billion in 2016, and we did $25 billion in 2017. And the reason for the jump in my view is all the spadework that we did in 2014 and 2015 and years before where we tested [the question of] how can you measure energy consumption and water consumption. The nice thing about this is that owners have to go in and change the showerheads, replace the HVAC system [anyway]. Owners are still going to do that stuff, but they’ll be smarter about how they’ll do that, and it will actually cost them less money. [They’ll say], “Wait a minute, this is better for me!” The owners only do what’s in their own interest.

What are the concrete upsides in this area that tenants and landlords experience?

At the end of the day, what I want to see is the tenant paying less rent because it’s a more energy-efficient building and therefore the landlord doesn’t have to raise the rent as much for utilities. It’s all about the planet, but it’s also about the people who live in the apartments, and working with apartment owners to reduce their cost, so maybe the rent on that apartment is a little less.

Overall, how would you describe the state of America’s multifamily housing stock? Are obsolete units getting replaced quickly enough?

More than 100,000 units per year have come online [in recent years]. The boom [in multifamily construction] happened when the baby boomers came of age, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Now, it just so happens that many of those apartments have been refurbished and kept up over time so they don’t become obsolete. But every year, to replace the ones that become obsolete is a challenge. The replacements do happen in the Class-A segment, but the real challenge is for the lower-income apartments or middle-income [ones]. Where working-class families live, with those apartments and those rents, that’s more difficult. There’s some good stuff happening.

Your website mentions that Fannie Mae has a key role in financing housing for American Indians. What’s that business like?

Generally, that’s through the low-income housing tax credit or single-family mortgages on trust land. It’s a different market, because those communities have different sets of laws. Every tribe has a tribal council. On trust lands, real estate law is what the tribal council says it is. Before you make the mortgage, you have to make some real agreements about, how can title convey? How can you prove ownership in default? There are all kinds of things you have to do. It’s part of our duty to serve.

Tell me about the team that you lead.

If you look at everyone who’s involved in the business, it’s about 600 people. I enjoy coming to work every day and having the privilege of leading these people. To a person, it’s a teamwork environment. People work together. It’s a sharing environment. People share information, and they’re friends. It’s an innovative environment. People think about strategy. The reason we have a green loans program is because we have people thinking about the future all the time. That’s the characteristic you get when you meet a Fannie Mae employee.

What’s the relationship like between Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? Do you talk about them at the water cooler?

What we have in common is we are both in conservatorship [under the Federal Housing Finance Agency]. We certainly respect the Freddie Mac folks, and they know what they’re doing. It is competition, but competition is good for us. And we’re on different models. Their model is a conduit model, and our model is a more typical insurance-company model.

I assume you’re the resident expert in the Hayward family whenever someone’s looking for a new house?

On a personal level, everyone [in my family] who takes a mortgage calls me up. You know, in general, there’s always someone out there looking not to give you a good deal. Fannie Mae has been big on homebuyer education, and we spend millions and millions of dollars [on it.] An educated consumer prevents disasters from happening.