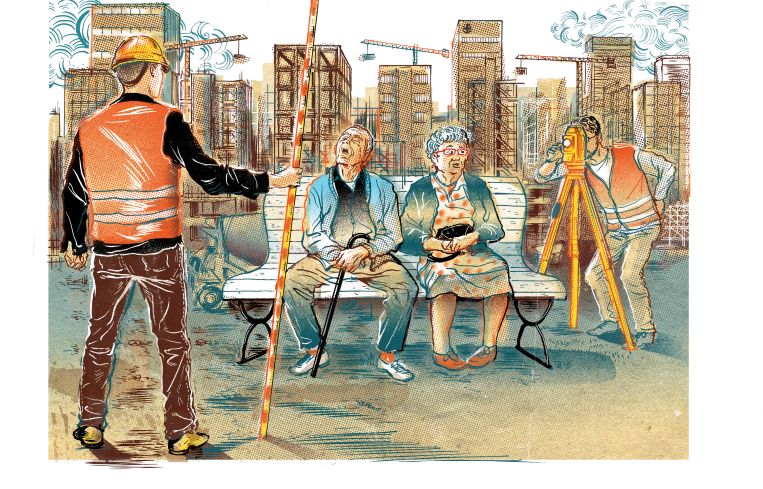

Senior Explosion: Developers Look to Cash in on Rising Older Population

With a nationwide 65-plus population on the rise, shrewd developers are building medical offices, hospitals and senior housing. How’s that working out?

By Christopher Cameron April 16, 2018 10:53 am

reprints

Soon after his death in Houston in 1939, the estate of Monroe Dunaway Anderson, a Tennessee cotton trader, wrote a $1,000 check to the Junior League Eye Fund. It was the first gift from a more than $19 million endowment that would eventually found the Texas Medical Center (TMC), a city within a city, squeezed between Rice University and the Houston zoo.

Today, Houston’s TMC is the world’s largest medical complex. With a gross domestic product of $25 billion, the center has gobbled up 2.1-square-miles of land supporting over 50 million square feet of medical institutions, housing and office space.

But even that isn’t enough—not in Houston, where the TMC has another $3 billion in construction projects currently underway, and not nationally.

The population aged 65 and older is expected to grow by 3.3 percent, or roughly 1.7 million this year. Over the next five years, that figure soars to 18 percent, or about 9.2 million, according to a CBRE report. Soon tens of millions of individuals will need health care services and assisted living facilities.

Meanwhile, health care employment has jumped by 47 percent since 2000, compared with 12 percent for total employment nationwide. The education and health services sector is expected to add nearly 1 million jobs over the next five years, according to the same CBRE report.

It’s a prospect that has developers eager to cash in on a niche within the commercial real estate market that is virtually guaranteed to blossom. Better still, health care is virtually recession proof, since, rich or poor, people will always get sick.

“Overall, the medical office market is strong,” said Andrea Cross, CBRE’s head of office research for the Americas. “It’s fueled by population growth, especially the 65 and older population, which is expected to double through 2055. We have seen health care employment growing at a much faster pace than overall job growth. It even continued to grow during the Great Recession. It was really the only sector to do that.”

The largest markets for health care services and development are areas with a perfect storm of aging residents, top universities and research and development activity, Cross said. Think Boston, Houston and South Florida. But she added that markets like Chicago, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis are seeing a lot of growth in the 65 and older population, fueling demand for medical growth in those areas.

Perhaps, surprisingly, New York City boasts the largest medical development pipeline of any major metro area in the nation, despite its restrictive and costly environment. Some 3.696 million square feet of medical office buildings are planned for the five boroughs, according to Revista data.

Medical providers have also become a major force in the battle for Manhattan office space. Cushman & Wakefield spokesman Michael Boonshoft said that seemingly overnight his firm was inundated with medical leases.

Boonshoft pointed to recent deals like 222 East 41st, where NYU Langone Medical Center took all 25 floors; 237 Park Avenue, where New York-Presbyterian Hospital paid nearly $251 million for 500,000 square feet of office space; 220 East 52nd Street, where Visiting Nurse Service of New York took 308,000 square feet; and 601 Lexington Avenue, where NYU Langone is in late-stage talks with Boston Properties to lease all 200,000 square feet. And that’s just to name a few.

“In 2017, medical became a major player in the top five industries that move the office market. It was a big surprise,” Boonshoft said. “Before a lot of these deals were taking place outside of Manhattan. That is the biggest change.”

One of the things that makes it possible for hospitals and medical care providers to lease space, he said, is super-pricy Manhattan is that they have become more efficient with their space. For instance, hospitals used to need huge amounts of space because they kept their offices in house, Boonshoft said. Today, hospitals tend to house their main offices off campus in less valuable space.

Paul Wexler, a New York-based Corcoran broker specializing in leasing medical facilities, said that the emphasis from his clients is on being patient centric, efficient with space and close to public transportation. He pointed to 555 Madison Avenue, where NYU Langone Medical Center expanded the Preston Robert Tisch Center for Men’s Health—a spa-like ambulatory health care center—at 555 Madison Avenue from approximately 14,000 square feet to 32,000 total square feet.

“We are also working on a brand new medical development [at 38-01 Queens Boulevard] in Sunnyside right now, half a block from the 7 train. On the first four floors there will be a Regal cinema and above it 120,000 square feet of medical space.”

So across the U.S. health care providers and developers have looked at the numbers and shaken hands. But it is yet unclear whether enough is being done in the right places to meet the impending demand—despite a national medical office building development pipeline of 229 buildings with a total of over 11 million square feet in the fourth quarter of 2017, according to CBRE (CBRE notes that their data excludes smaller medical offices that might be, say, at the base of a new condo building in Manhattan). The market clearly seems to believe that it could handle quite a lot more.

“Two years ago there was an estimated shortage of 63 million square feet of ambulatory medical office space. Now, that is in an ideal world. But in my opinion the demand is probably two thirds of that today,” said Chris Kay, the president and COO of Hammes Company, which is ranked the largest developer of medical properties in the nation by Modern Healthcare, a trade journal.

“There is a lot of demand and there is a lot of inventory,” Kay said. “It is just that the inventory that is out there is not well aligned for the with what the industry is pushing. The industry is pushing experience-based interaction between the physician and the patients. The trend today is for collaborative interdisciplinary environments. But a lot of the traditional medical office buildings out there were built in the 70s or 80s and are outdated.”

Christopher Bodnar, the vice chairman of CBRE’s Healthcare Group, added that “there is pent up demand by developers, who are compressing yields down to win deals. On the acquisition side there is a significant amount of demand to place capital.”

So what gives? Why isn’t more being developed to meet demand from both developers and patients now and in the future?

That is where things get complicated.

Politics, technology and the highly specialized nature of the industry means that health care providers are slow to act and that few developers are actually equipped to deliver.

For instance, changes to the Affordable Care Act could leave millions uninsured, and typically, health care developers and providers target areas with a highly insured population.

Kay said that as it stands the American health care system has already left developers and providers scratching their heads.

“Projections show that there will be all of these old people in the world and we are going to need to take care of them via assisted living or senior housing. I’ll buy that. But if there is so much demand, why is occupancy in these facilities only 82 to 90 percent?” he said. “The reason is the reimbursements. These places are expensive. On the very low end, depending on what part of the country you live in, they are about $4,700 a month. If you are in New York, they are $12,000 a month. The national average is $6,500 a month. So how does a person afford that? It is very, very difficult when social security or Medicaid only pays $1,200 a month.”

The average stay in an extended care facility is one or two years, depending on the type, he said. And that’s because, by that time, most people have blown through their savings.

“You have big turnover,” Kay said. “Everyone is trying to figure out models for making this work. How do you lower the cost of taking care of patients?”

Meanwhile, rapid technological advancement and the rise of video conferencing mean that facilities are shrinking.

In recent years, IBM, Google and Amazon have all been jumping into the health care space with artificial intelligence technology with the goal of bringing care out of the hospital or doctor’s office and into a patient’s home.

That is having an impact on what is actually being built and at what pace. Less space is necessary than in traditional facilities and parallel practices are being crammed into the same buildings.

“The anchor to a building may be a surgery center. Then a parallel practice may want to go into that building. For instance, an orthopedic group,” Bodnar said. “These buildings are like ecosystems.” A typical medical office building is between 30,000 and 70,000 square feet today.

“The digitization of the health care industry is changing things so quickly that it is creating uncertainty,” Kay added. “Nobody knows where it is going to go or what is needed.”

Those factors mean that speculative development in the health care field is basically unheard of. Each project is essentially a one-off custom job that meets the specific needs of specific tenants.

“The amount of developers out there who would like to be building medical buildings on behalf of providers is significant. But the health systems have been very disciplined in their expansion strategy,” Bodnar said.

And not just anyone can do it. Far more so than in traditional commercial development, medical developers work closely with the nonprofits and provide them with everything from market research to the physicians themselves.

“There is a lot of nuance to medical development that goes beyond brick and mortar,” Bodnar said. “That’s why these groups that specialize are able to do it across the country.”

The top medical developers, according to Modern Healthcare, after Hammes include Navigant, JLL and Nexcore Group.

“Providers usually need a developer who can provide services like market strategy—which has to do with determining the size of the building,” Bodnar said. “They look at physician supply and demand. They are doing heat maps to find voids in patient service areas. They do physician recruitment, so a specialist developer needs to be accustomed with how a physician works. These developers are talking about optimizing workflow and talking about fostering collaborative care environments. And in some cases, they are providing specialty design, so that the ambiance conveys a sense of healing.”

But even at the current pace, naysayers exist.

At a conference last year, David Park, the senior vice president of real estate and construction at Novant Health, forewarned of a bubble in the medical office sector, saying, “MOBs are not like bank branches.

“At some point in time, what you start looking at is: When does that population growth, that bell curve, start down?” he said at the Bisnow event in Atlanta. “At some point that number is going to drop.”

It’s just another example of how complex and opaque the market for health care facilities is—a fact perhaps reflected in the caution being seen on the provider side.

Back in New York, where the pipeline is largest, hospitals and providers are looking more carefully than ever, Wexeler said.

“There are really only pockets of development. There is just not a lot of opportunity for medical to be developed,” he said. “Everyone is being diligent.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)