A Massive Rezoning Promises to Remake the Central Bronx

By Rebecca Baird-Remba February 15, 2018 9:45 am

reprints

Beneath the elevated 4 line on Jerome Avenue in the Bronx, auto shops bump up against drug stores and bodegas, pizza places and dollar stores, schools and doctors offices, hair salons and juice bars. Noisy, dirty muffler repair and auto glass shops dominate blocks and blocks of the busy thoroughfare, but a city plan to encourage redevelopment in the neighborhood is raising questions about the fate of the auto shops and their workers.

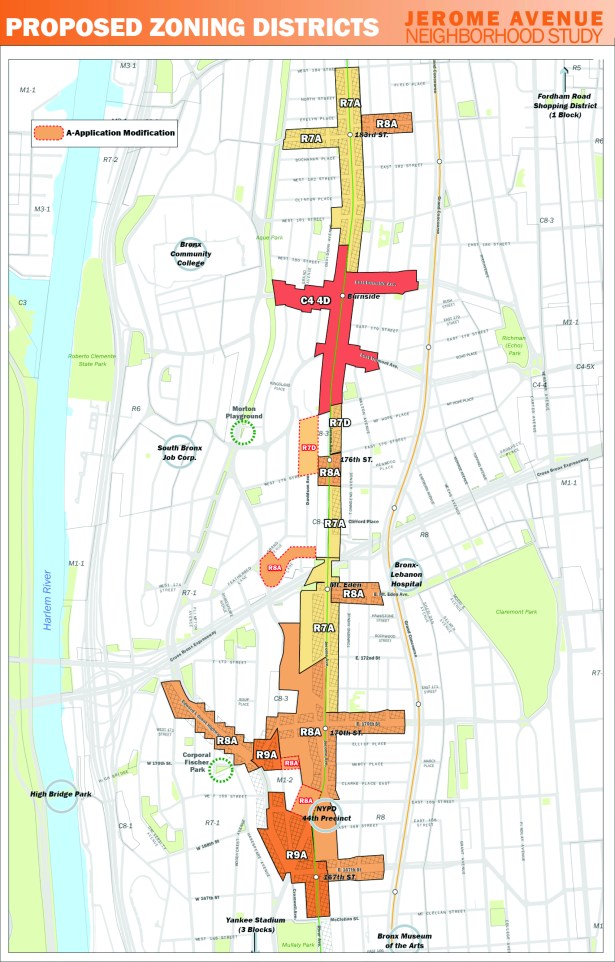

After three years of planning and contentious public meetings, the city is finally getting ready to rezone 92 blocks of Jerome Avenue, running from 165th Street in Highbridge to 184th Street in University Heights. Along the way, Jerome also passes through Concourse, Morris Heights, Mount Hope and Fordham Heights. These are some of New York City’s poorest neighborhoods: The median family income hovers around $25,900 in Bronx Community Districts 4 and 5. Two thirds of the housing stock is rent-regulated, and 80 percent of the apartments and homes were built before 1947, according to the Department of City Planning.

Most of Jerome is zoned for heavy commercial uses, like auto shops, parking lots, car washes and gas stations. And while the car repair industry and various kinds of small shops have proliferated, residential development is nonexistent. In early 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration realized that the strip of low-rise commercial buildings along Jerome was ripe for redevelopment, and the neighborhood could play an important role in the mayor’s initial plan to build and preserve 200,000 affordable units by 2022. (The administration upped its goal last November to 300,000 units by 2026.)

The rezoning is expected to pave the way for new mixed-use, midrise residential buildings—up to 4,000 apartments, 440,000 square feet of retail and 40,000 square feet of offices across 45 development sites. And the new construction would displace roughly 98,000 square feet of auto-related businesses and 48,000 square feet of industrial space, according to city zoning documents. While the city has promised to spruce up local parks and improve lighting under the elevated subway tracks, activists wonder whether the new zoning will ultimately put the owners of auto shops, as well as their hundreds of employees, out of work. Neighborhood groups are also uneasy about how much of the new residential construction will be affordable for locals.

“Our community cannot be expected to accept additional density without seeing significant investments made in our neighborhood that we truly need today, that we needed yesterday, and the day before that, and the day before that,” City Councilwoman Vanessa Gibson said during last week’s hearing. “This plan cannot and must not move forward without real investments and protections for our residents and small businesses.”

She’s pushing for the city to build several hundred new school seats in the neighborhood, fund the renovation of 12 parks, commit to a local hiring plan for construction projects and develop a plan to help potentially displaced auto shop owners and workers.

Jerome Avenue will be the fourth major neighborhood rezoning orchestrated by the de Blasio administration, after the fiery and rushed effort to revamp East New York, Brooklyn, approved in April 2016, the under-the-radar rezoning of Far Rockaway, Queens, and the drawn-out, contentious rezoning of East Harlem that passed last November.

“Overall the neighborhoods that are being rezoned are mostly low-income communities of color,” said Emily Goldstein, a senior campaign organizer at the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development (ANHD). “They’ve all had many years of disinvestment, and now they’re facing this idea that, in order to get reinvestment they’ve needed all along, it has to come with a rezoning. I think there’s huge concern of how these shifts in the market will affect displacement. There’s a question of what’s going to get built and for whom.”

On the housing front, advocates have scored two major victories since the city held its first round of public meetings on Jerome in the summer of 2015. Last year, the City Council signed off on two major pieces of tenant legislation that will help protect the working-class, rent-stabilized tenants of the south and central Bronx from displacement. The first, passed in April 2017, was the right to counsel in housing court, which guarantees a pro-bono lawyer for all tenants facing eviction who earn up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line. The second was the creation last November of a certificate of no-harassment program (CONH), which requires landlords to prove to the Department of Housing Preservation & Development (HPD) that they have not harassed tenants in order to get building permits for new buildings or demolition.

The Jerome Avenue proposal has wound its way through several stages in the seven-month-long public review process, winning conditional approvals from Community Boards 4 and 5 and the Bronx Borough President. Last Wednesday, a City Council subcommittee held the final public hearing on the rezoning, before the plan heads to the full council for a vote and final approval in late March. In the meantime, the area’s two councilmembers, Gibson and Fernando Cabrera, will hammer out the finer points of the land-use rules and community benefits with the de Blasio administration.

Auto Shops Being Driven Out for Good?

Despite some key housing victories, neighborhood activists still worry about the fate of Jerome’s auto shops, which are largely owned and staffed by Spanish-speaking immigrants. The majority of auto repair workers along Jerome only have a high school education, said Pedro Estevez, the head of the United Auto Merchants Association. Since many of the auto shops will inevitably be priced out of Jerome, he argued that the city should step up and fund new training programs, relocation costs and initiatives to help bring the remaining auto shops into compliance with the new zoning. The strip holds roughly 200 car-related businesses, car washes, gas stations, used car sellers and auto repair, muffler, glass and tire shops. Eighty-nine percent of those businesses only have one-year commercial leases or no lease at all, according to Estevez. City planning documents predict that 43 auto shops and 45 non-auto-related businesses are likely to be pushed out, but critics think those are low-ball estimates.

During last Wednesday’s public hearing, Estevez unveiled an “Auto Business Readiness Plan,” which would create a $4.5 million training center that would offer workshops and classes to workers and help them learn new automotive technologies. He also pitched the idea of developing a new five-story commercial building that would house up to 200 car-related businesses as well as ground-floor retail in a different Bronx industrial area.

“The city’s not offering anything,” Estevez told Commercial Observer. “They’re going the same route as Willets Point. But they’re using a rezoning instead of eminent domain…When the Bronx was burned down, these [business owners] built that [Jerome] corridor out of the ashes. They put their blood, sweat and tears into it, every day, rain or shine, coming to work.”

At Willets Point, next to Citi Field in eastern Queens, the city has seized several blocks’ worth of auto shops through eminent domain to clear space for a planned development with 1,100 affordable apartments, a school and retail. Some business owners, faced with the costs of setting up shop elsewhere, simply closed, and hundreds of Latino autoworkers lost their jobs. Forty-five auto shops tried to relocate to an auto mart in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx called Sunrise Cooperative. The city Economic Development Corporation gave Sunrise $7 million to help the group rent the warehouse at 1080 Leggett Avenue and build out a new home for their operations in 2014. Then after the group fell behind on its lease, the agency provided another $2.5 million last year in order to help Sunrise catch up on its rent. But the landlord refused to accept the cash and ultimately evicted the auto shops last fall.

Back on Jerome, planning officials said that the city expects to offer loans of up to $250,000 to small businesses that want to grow, relocate or meet the new zoning requirements by getting the right licenses or permits. A spokeswoman for the Department of City Planning also pointed out that the plan for Jerome has been changed to ensure that a few blocks of industrial, auto-business-friendly zoning remain along the corridor.

Gibson also said that she wanted the city’s Department of Small Business Services to create community coordinators that would help owners on the corridor navigate challenges created by the rezoning and educate them on city-backed grants and loans for small businesses.

“I’ve always had a commitment to protecting as many of the auto workers as I can,” Gibson said. “No one likes the way [Jerome] looks today. But [improvements shouldn’t come] at the expense of displacement…I don’t want to repeat the failed venture at Willets Point. The challenge is that if they stay, how do we allow them to operate better, to look better? We want to offer them a chance to move to another part of the Bronx. I don’t want to hear from the city that the only thing we have to offer small businesses is a loan. ”

‘Affordable for Whom?’

Before one of the first big public meetings on Jerome in October 2016, more than 100 neighbors marched up University Avenue to Bronx Community College’s library and chanted, “Whose Bronx? Our Bronx!” and “Affordable for whom?”

Many housing advocates and developers agree that for now, most of what will be built along Jerome Avenue will be subsidized affordable housing. Adam Mermelstein, whose firm Treetop Development is building a 400-unit residential project in the South Bronx neighborhood of Mott Haven where 20 to 30 percent of the units will be affordable, said that the rents along Jerome are still too low to support the construction of housing without subsidies.

“I think it’s going to be difficult for folks like myself to come and build market-rate unsubsidized units in this area, at least at the current rent levels of the central Bronx,” he said. “I think the first wave will be the tax-credit developers or the affordable developers, and then the later wave will be the market-rate developers.”

The open question is, Just how affordable? Will the average family in Highbridge or University Heights, earning $20,000 or $30,000 a year, be able to rent an apartment in one of these new developments? The answer is a little unclear.

Gibson predicts that roughly 45 percent of the housing constructed in the wake of the rezoning will be permanently affordable. However, she doesn’t think the city will be able to provide a breakdown of how many of those units will be within financial reach for low-income renters. The HPD is in the midst of financing several below-market development projects in the neighborhood, Gibson said, and existing affordable-housing financing programs will help ensure that some percentage of the new units house folks earning $30,000 or less. (Planning documents predict that 2,243 low- to moderate-income units will be built by 2026, but they don’t say how many will be affordable to current residents. An HPD spokesman said it will encourage developers who use city financing programs to build 100 percent affordable housing. However, the agency said it can’t predict exactly how private land owners will develop their sites and couldn’t give estimates of how much low-income housing will be built after the rezoning.)

A handful of landowners in the area have already committed to building 100 percent affordable housing. Maddd Equities, for example, is planning 720 below-market rentals at 1159 and 1184 River Avenue, set to be financed through HPD’s Extremely Low and Low Income Affordability (ELLA) program.

Since the city reduced the size of both the East New York and East Harlem rezonings, activists argue that the Jerome rezoning—which has actually grown to cover 22 more blocks as the planning process has advanced—should be cut in half. Members of the Bronx Coalition for Community Vision contend that the new zoning should cover 46 blocks, instead of 92, and produce 2,000 units instead of 4,000. If there are fewer new units built, it’s more likely that the city will be able to subsidize them and create a generation of entirely below-market housing. And a smaller rezoning will affect fewer existing residential buildings. That means fewer landlords of older rent-stabilized properties would have incentive to cash in on rising property values by harassing tenants or selling, activists claim.

A smaller rezoning might also mean less gentrification when the central Bronx finally can support new market-rate housing, which could be in the next decade or so.

“Ten years is not that long in the landscape of a community,” said ANHD’s Goldstein. “What are the shifts going to be? And to what extent is this rezoning going to move those faster and in the direction of less affordability?”

Jason Gold, an investment sales broker at Ariel Property Advisors, compared Jerome to the rezoning of Mott Haven in 2009. After several years of sluggish real estate activity, the formerly industrial South Bronx neighborhood is suddenly flush with new, market-rate construction. Chetrit Group and Somerset Partners are building a 1,300-unit, six-tower market-rate rental complex along the Mott Haven waterfront, and Tahoe Development is putting up a 47-unit condominium project at 225 East 138th Street. There’s also Treetop’s two-building development at 414 Gerard Avenue, which will be 70 to 80 percent market rate, with the remainder of the units renting through the affordable housing lottery.

While the new zoning along Jerome might push up investment sales numbers and property values, Gold agreed that developers aren’t going to build much market-rate housing there in the next few years. The development potential of many sites on the corridor will quadruple overnight, but “I don’t see a developer buying a property that was recently rezoned and kicking tenants out,” he said.

Bulwarks Against Displacement

Pumping subsidy and tax credits into rent-regulated buildings has long been a way to prevent low-income tenants from being priced out. And the de Blasio administration has proudly pointed out that it struck deals to preserve 5,500 rent-stabilized apartments over the past four years in Bronx Community Boards 4 and 5, which cover the neighborhoods affected by the rezoning. The city has also pledged to preserve an additional 1,500 units near Jerome in the next two years.

But Gibson said that she’ll push for the city to protect 2,500 or 3,000 units in the same period, because the neighborhood will be ripe for displacement and harassment. Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. backed her up with a report released last week that identified 2,075 units within a quarter mile of the rezoning area that it considered a high priority for city preservation efforts. Properties on the list had high numbers of building violations, were already enrolled in some kind of subsidy or tax credit program and were in census tracts with larger families and lower incomes.

One of the best ways to prevent poorer Bronxites from being pushed out of the neighborhood could be the CONH program—if it works. The pilot program, set to launch at the end of August, will require some residential landlords to prove that they have not harassed current or prior renters in the past five years to secure permits for new construction, major alterations or demolition.

HPD has created a “building distress index” that will tell the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) know which properties to flag when those owners seek permits. Buildings that have been sold recently, changed hands repeatedly over the last couple years, racked up a significant number of code violations or been issued a full vacate order would all make the list, as would ones where the landlords have been found guilty of harassment in the past. The list of properties would be public, so tenant advocates will know when those landlords apply for permits and be able to educate tenants in those buildings on their legal rights.

The program hinges on the HPD and the DOB sharing data and ensuring that the right properties get flagged when their owners apply for building permits. The agencies have nine months, beginning when the CONH law was passed last November, to set up those databases and notification systems. An HPD spokesman said the agency anticipates a smooth rollout of the program and expects to meet the fall 2018 deadline.

Councilman Brad Lander, who sponsored the legislation and organized the task force that drafted it, said, “We’ll be watching closely and exercising oversight. They [HPD and DOB] agreed to work with us on this task force process.”

But he does worry that tenants who are being harassed or have already been harassed out of a building will be afraid to talk to HPD about their experiences.

“I’m concerned that there are situations where harassment has occurred, but this system won’t detect it,” he explained. “In some cases where harassment took place, it will prove difficult or impossible for those tenants to make their case.”

Lander argued that his new citywide version of the certificate would discourage harassment while still allowing developers to build new housing and renovate older buildings. Still, CONH programs in neighborhoods like Hell’s Kitchen have created hurdles for landlords looking to renovate or sell.

“It definitely presents challenges for a landlord who’s looking to buy that kind of building and renovate it and re-let it,” said Treetop’s Mermelstein. “I think that will stymie some development in this area, and it discourage some investment.”

Goldstein, who also worked on the CONH legislation, said, “It has a lot of potential. It all rests on the idea that landlords are harassing their tenants because of how much money they can make in the future, and if we mess with that calculation, they’ll hopefully stop.”