Street Retail Looks to Malls in Figuring Out Ways to Cope With Big Rents [Updated]

By Lauren Elkies Schram December 7, 2017 12:00 pm

reprints

While malls and shopping centers are looking for ways to save themselves from crushing retail headwinds, at least one group thinks they’ve got something to learn from them: street retail.

The guys with the shops on the sidewalk are taking a page out of their playbook when it comes to structuring deals.

Young retail companies, e-commerce brands and even some legacy retailers looking for a brick-and-mortar presence are asking for terms long found in shopping centers—low base plus a percentage rent (meaning the retailer pays the landlord a certain percent of every dollar in sales over a certain threshold).

“That shopping center formula has morphed onto certain streets—not all streets—around the country. [It] sometimes bridges a gap between what a landlord is looking to achieve with his overall rent and what the tenant feels they can pay with respect to what their sales projections are,” said tenant representative Virginia Pittarelli, a principal of Crown Retail Services (an affiliate of Crown Acquisitions).

These percentage-rent-plus-base deals allow retailers to test out the market with minimal risk by not being locked into a guaranteed rent and give landlords an activated space along with some income. Such deals are being done across the retail spectrum and around New York City for leases as long as 10 years.

Typically in base-plus-percentage-rent deals, the landlord gives a 20 to 50 percent discount to market gross rent, plus a percentage of sales between 8 and 12 percent, according to Christopher Conlon, the executive vice president and chief operating officer of real estate investment trust Acadia Realty Trust.

Robin Abrams, a vice chairman of retail at Eastern Consolidated, explained the percentage-rent formula as follows: If the rent is $500,000 per year and the tenant agrees to a percentage rent of 8 percent above a natural breakpoint (where the base rent equals the percentage rent), the calculation is $500,000 divided by 8 percent with that 8 percent equaling the natural breakpoint above which the tenant pays. So a tenant would pay 8 percent of sales in excess of $6.3 million annually. As the rent increases over the term, the natural breakpoint increases.

“Sometimes the landlord requires an unnatural breakpoint,” she added, “and might say to the tenant that he wanted a million [dollars] in rent, and he won’t wait till sales are $6.3 million but wants the percentage rent over sales of $5 million, or whatever minimum sales figure landlord and tenant agree.”

Abrams and her team are submitting an offer for a restaurant space in an “unchartered neighborhood” where the asking rent is $1.4 million per year. The offer includes a base rent of less than half of the asking rent along with a percentage rent at lower than the natural breakpoint.

These deal structures aren’t confined to less trafficked and less high-profile areas of the city.

Lee Block, an executive vice president at Winick Realty Group, said that while he hasn’t closed any deals that incorporate a percentage-rent component, “we’re considering it on a handful of spaces that we represent.” That was the message conveyed by many brokers and landlords with whom Commercial Observer spoke.

The reason? A surplus of space and a changing retail climate.

Jared Epstein, a vice president and principal at real estate developer Aurora Capital Associates, said his company is negotiating a few deals in Soho with a “slightly reduced base rent and feature a percentage rent above a natural breakpoint, which we believe will enable the landlord, our entity, to attain market rent and likely exceed market rent so long as the store does the volume that we believe it will.”

And that is because of the high vacancy rate in Soho, Epstein said.

“In general,” Epstein said, “in any deal that features a percent rent in lieu of an amount of fixed rent, the landlord hopes to set a low break point and a large enough percent above that, which will make it probable that the landlord will achieve the total base rent it hoped to achieve. The landlord has to believe the retailer will do the business to get the landlord back to its base rent. Sophisticated landlords will offer the downside protection of a discounted base rent in this market but will also want to participate with the tenant on the upside as their business outperforms.”

For most deals to get done, then, landlords need to be flexible.

“In the last 12 to 24 months I think owners that can be more creative with percentage deals are doing it,” said Jeffrey Roseman, a founding partner of Newmark Knight Frank’s retail division. “Not every owner has the ability to do it because they may have certain restrictions from their bank or they may have paid too much for the property. [But] it’s a new creative way to get deals done.”

True, landlords need to be open to different deal structures, Conlon said. While Acadia hasn’t done deals for a low base plus percentage rent, it is “considering them now,” he said, adding that Acadia would only do them for short-term deals, or those less than three years.

While this structure is a way to get deals done, landlords start “getting in under the hood and the tenant’s don’t want that,” said tenant broker SCG Retail’s David Firestein. Also, tenants don’t like sharing their sales figures.

He added: “When you give percentage rent, then landlord’s want to be involved with sales, days and hours of operations, as well as ‘continuous operations’ [meaning you have to operate for the duration of the lease at whatever hours outlined in the agreement].”

And not all landlords are biting.

![Street Retail Looks to Malls in Figuring Out Ways to Cope With Big Rents [Updated] gettyimages 520141660 Street Retail Looks to Malls in Figuring Out Ways to Cope With Big Rents [Updated]](https://observer-media.go-vip.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/12/gettyimages-520141660.jpg?w=615)

Triangle Assets doesn’t plan to do any percentage-rent-involved deals, according to Benjamin Stavrach, the director of leasing and property management at the company.

“New tenants have talked to us about percentage-rent deals, and we have held back,” Stavrach said. “It’s a different business model. It’s not something we want to get our hands dirty with. [And] as a landlord I don’t have to give it.”

With percentage-rent deals, he noted, a landlord has to “trust” the tenant will be successful and is honest with its sales records. “You are almost investing in the tenant,” he said.

Instead, to get deals done, Triangle Assets—with its 83,000 square feet of street retail space—may lower the rent in a gross-rent deal.

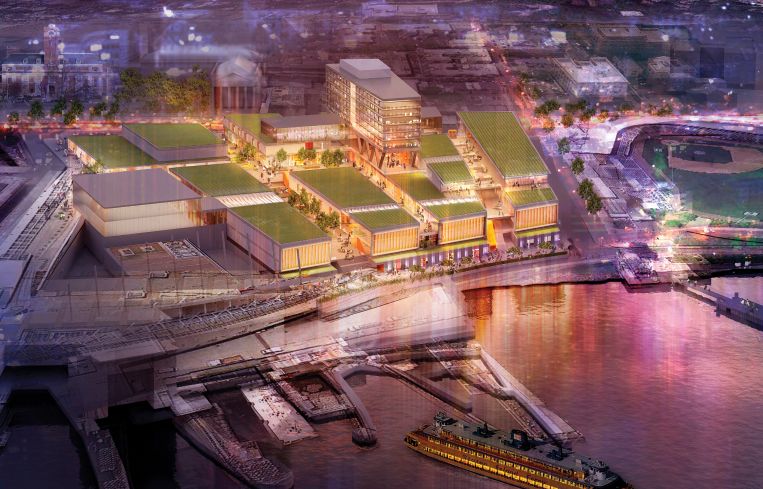

Michael Brais, a food-and-beverage retail broker with Douglas Elliman Commercial, who is leasing up the F&B component at the BFC Partners-led Empire Outlets outdoor shopping center on Staten Island, said he is working a lot with the percentage-rent structure.

Indeed, at Empire Outlets, the F&B component totals 50,000 square feet, of which 5,000 square feet remains available. Almost all the deals were negotiated with a combination of base plus a percentage rent, and the same goes for the majority of Brookfield Property Partners’ retail agreements.

That structure can be a win-win for both sides of a deal, some brokers said.

“It is fairly established, particularly in shopping centers with base and percentage rent,” Brais said. “Lower base helps the operator hedge against lower sales and helps the landlord participate in the upside.”

Malls and shopping centers historically have implemented the percentage-rent formula as a “hedge against inflation,” Conlon said. Without such clauses, rent increases are typically a “modest 1 to 2 percent annually or 10 percent every five years.”

Thomas Dobrowski, an executive managing director with Newmark Knight Frank based in New York City, handles regional mall investment sales nationally. He said the formula started to become more popular after the 2009 recession, “when dozens of malls were foreclosed on by lenders and special servicers. To placate tenants and keep them at these properties that were distressed and transitioning, percent-rent deals, along with short-term leases, became more common and enabled new owners of these malls to keep many national tenants that would have closed open and operating. The trend continues today and is becoming more common at stabilized properties as well.”

This model is good for tenants in a market where rents are outrageously high, but it’s good for landlords when the tenant does gangbusters business. In this market, it is more beneficial for the tenant.

“The tenants have the upper hand these days,” Dobrowski said. “These national retailers have a lot more leverage than they did in the past, and they are exercising whatever rights they have or proposing structures that are benefitting them.”

One of the things holding landlords back from doing too many percentage-only deals, which are very common in enclosed malls, is they can make the real estate difficult for lenders to underwrite. The underwriters “don’t like to see zeros anywhere,” Brais said.

While Conlon doesn’t think inclusion of percentage-rent will become the new “norm for deal-making,” Brais said he expects percentage-rent deals to “become more prevalent” because of the difficulty of getting spaces rented.

For now at least, deal terms are changing.

“Across the board, all streets, all landlords are being creative because we have an abundance of available space in the market,” Pittarelli said. “And the best for any type of market like this is to fill those spaces and if you can fill those spaces by being creative and working with a credit-worthy, great-image-quality retailer, why wouldn’t you?”

Update: This story was edited to include more of a tenant’s perspective from David Firestein of SCG Retail.