Milk, Honey, Bonds: Despite Market Troubles, Retail Landlords Are Raising Money in Israel

By Rey Mashayekhi May 3, 2017 10:30 am

reprints

In a retail environment often characterized as the worst in a decade, there is still one place where retail landlords can find refuge from challenging headwinds—and where investors are willing to back their businesses with tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars.

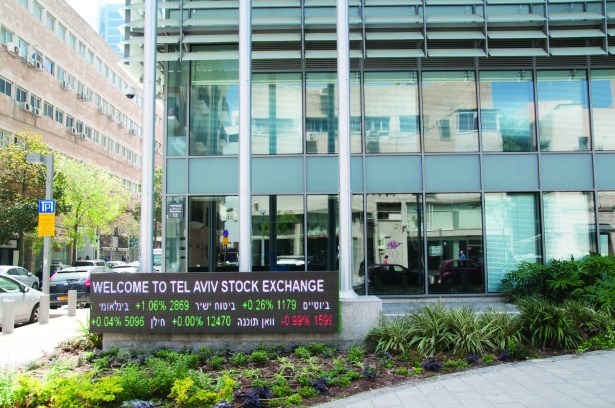

Israel’s bond market has emerged in recent years as an increasingly popular vehicle for U.S. developers and landlords to raise capital. Using their American real estate assets as collateral, companies—particularly small to midsized players that usually have to rely on mezzanine debt to finance their holdings individually—are able to issue publicly traded, corporate-grade debt at borrowing costs far below what they’d be able to secure in the domestic lending market.

Despite difficult conditions in the retail market nationwide, U.S. retail landlords are now looking to Israel more than ever before and finding success through bond offerings on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. In February, retail mogul Jeff Sutton of Wharton Properties issued around $245 million in debt in Tel Aviv at an interest rate under 4 percent, with the bonds backed by a portfolio of Sutton’s prime Manhattan real estate assets.

Other retail players have gotten in on the game as well. In March, New Jersey-based retail and shopping center landlord The Klein Group raised roughly $25 million through its own debt offering—the company’s second such deal on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (it raised roughly $60 million in an initial offering in 2015).

And in early 2016, developer Michael Shah’s Delshah Capital raised north of $100 million through a bond issuance backed by Shah’s Manhattan retail properties like 55 and 69 Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District (as well as a considerable 1,000-plus unit portfolio of rent-subsidized apartments).

All of this activity has taken place against a backdrop of concern for the U.S. brick-and-mortar retail market. From trendy storefronts in Soho to shopping centers and strip malls in suburbs across the country, retail landlords have been forced to cope with store closures (which are on pace to exceed 8,600 nationally this year, according to an analysis by Credit Suisse released in April), heightened vacancy rates and a drop in taking rents.

Despite their willingness to invest in bonds backed by U.S. retail assets, the Israeli investors who are pouring money into the Tel Aviv bond market are far from blind to the issues that retail landlords are presently facing.

“We’re constantly being asked questions by different investors: ‘What’s the situation [with the U.S. retail market]?’ ” said Yossi Levi, the vice president of Tel Aviv-based financial consultancy InFin, which has advised companies including The Klein Group and Delshah Capital in their Israeli bond offerings.

Levi said that the investment community in Israel is particularly aware of the issues being faced by big-box retailers like Sears and Macy’s, which have announced significant store closures in recent months, and are curious whether such issues within the retail sector at large could possibly affect the real estate companies that have issued bonds in Tel Aviv.

“The ratings agencies are educated about the situation,” he noted. “There is risk exposure in the retail sector; there are vacancies, and it’s scary [for investors]. The main issue is that people bought [retail properties] knowing rents were very high, and now prices are dropping.”

That naturally raises questions about whether American issuers with retail properties—assets whose projected income and cash-flow are a critical part of the metrics used by investors in evaluating companies—will face struggles in the near-term and perhaps even find it difficult to pay back the debt.

With concerns mounting among investors, the onus has fallen on the companies whose bonds are trading on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (as well as their advisers) to explain to the market why they are positioned to survive the current conditions.

“Israeli investors are extremely well informed; they know that retail is not shining at the moment—at least not in the newspapers,” said Jacob Klein, the president of The Klein Group. “When we did our second raise in March, we explained to investors that not all retailers are the same. Obviously, retail is shifting and changing, but not everybody is painted with the same brush.”

Klein, who owns retail properties in Manhattan as well as shopping centers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, said he told investors his company has little exposure to “big-box” retailers and that its properties are well served by their location to population centers and a diverse tenant mix.

“It’s harder today to find fashion tenants in Manhattan or New Jersey, but there is big demand from food users—every day there’s a new food concept coming up, and they’re all looking for locations,” Klein said. He also noted that service-based retailers are “still thriving,” as well as drug stores and grocery stores (Klein signed Trader Joe’s at his retail condominium unit at 660 Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side last year).

But Klein and other retail landlords whose companies are now publicly traded entities in Israel still have to play the game of investor relations when it comes to easing market concerns.

“They say, ‘Well, we read that retail in Manhattan is terrible, rents are dropping, vacancies [are rising]’—they know all of this, and they ask direct questions,” Klein said of what he hears from his investors in Israel. “And I tell them, if you look at our portfolio, we are at 98 percent occupancy. We lose a tenant here and there, but we keep working on leasing everything up.”

Shah said that when Restoration Hardware—one of Delshah’s larger tenants, at 55 Gansevoort Street—saw its stock price take a hit in recent months, “I had a few questions from Israeli bondholders about what was going on and whether we were concerned about the lease.”

But Shah said he addressed those worries by explaining that Delshah’s base of stable, credit tenants with long-term leases—including the likes of major clothing retailers J. Crew and the Urban Outfitters-owned Free People—would cope just fine. “I told them I was more concerned that I bought the [Restoration Hardware] stock.”

Long Island-based Namdar Realty Group, a retail owner that completed a $125 million bond raise in Tel Aviv late last year, has faced similar concerns. The company, which owns 15 million square feet of commercial real estate at shopping centers across the country, found itself having to explain to investors that Sears’ recent struggles (the company has announced around 150 store closures in the last few months) would not greatly affect its own business.

The day after Sears announced a recent wave of closings nationally, Namdar and its Israeli market advisers delivered a report to investors detailing the landlord’s exposure to the retailer, according to Israeli market sources—explaining how less than 3 percent of the Namdar portfolio’s operating income came from Sears.

As for Sutton—whose portfolio of assets backing his Israeli bonds include prime Manhattan properties like 747 Madison Avenue, which houses Givenchy—retail concerns didn’t hinder the significant demand his debt offering commanded from Israeli investors, which could have supported a bond issuance of more than twice the $245 million Sutton eventually raised.

Like Delshah, Wharton Properties’ base of credit tenants—with lease lengths exceeding the actual duration of the bonds issued—has served investors well so far. The company’s bonds have recently traded at around a 3.7 percent yield on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, below their initial coupon. (Sutton declined to comment for this article.)

But that doesn’t mean that retail-focused real estate players who may look to raise debt in Israel in the future will find the same success, particularly if the brick-and-mortar retail environment continues to deteriorate.

“Remember that we’ve been in this market for almost two years and are close to our investors,” Klein noted. “If I was going to issue new bonds today in Israel, strictly backed by retail, it would probably be a tougher sale to make because of the general environment.”

Retail landlords opting to tap the market in Tel Aviv could expect numerous questions from the investment community about why their company is exempt from retail’s current travails, and “they should be prepared to answer them,” Klein said. “The first question would be, ‘Why is retail in the doghouse? ’”