The Power Disruptors: The Players Who Are Upsetting Real Estate’s Status Quo

By Rey Mashayekhi April 27, 2017 10:00 am

reprints

In today’s economy, change is inevitable. New ideas and innovations constantly transform the way people do business. As the technology sector has grown—permeating nearly all aspects of the global economy—every entrepreneur is seeking the next big, disruptive product or platform. Traditional industries, especially, have appeared ripe for disruption by tech-focused companies.

Real estate has been no exception to this. The industry is perpetually evolving, with companies ranging from established internet giants to plucky tech startups bringing fresh approaches to the table. For a business that has a reputation as being manned by dinosaurs—unwilling or unable to change—real estate has fostered a remarkable variety of innovations in recent years.

This has forced the remaining dinosaurs to adapt or be left behind. But in a twist, many disruptive companies are now veering back into their respective industries’ traditional spaces after they’ve carved out—or eviscerated, in some cases—those models.

Here are some of the companies who are disrupting the status quo in 2017.

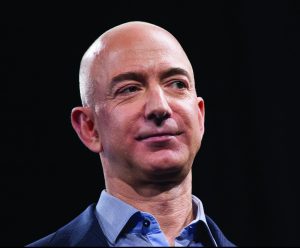

Jeff Bezos, Amazon

Jeff Bezos’ online retail behemoth has already made life miserable for brick-and-mortar retailers internationally by making the shopping experience—for virtually every product imaginable—as easy as clicking “buy now.” While the retail market’s troubles are not exclusively down to Amazon, it’s indisputable that the rise and growth of e-commerce has contributed to the current state of affairs—with retail store closings nationally on pace to exceed 8,600 this year, according to Credit Suisse.

Amazon, meanwhile, expects to add 30,000 new part-time jobs over the next year, including 25,000 at its vast network of warehouses (which have attracted much criticism over alleged labor abuses and poor working conditions, it should be noted). Perhaps ironically, the company is now veering into the brick-and-mortar sector itself: Beyond plans to open up to 100 pop-up locations across the country (it had only 16 as of last August), Amazon is following the 2015 opening of its first physical bookstore in Seattle with locations in New York City.

In January, it was reported the company would open its first New York bookstore at a 4,000-square-foot location inside the Shops at Columbus Circle, at Related Companies’ Time Warner Center. And this month, it emerged that Amazon would open a second store at Vornado Realty Trust’s 7 West 34th Street in Midtown.

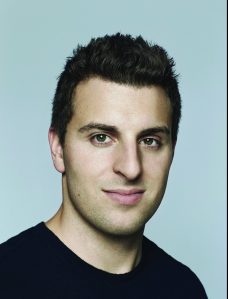

Brian Chesky, Airbnb

Much as Airbnb has disrupted the hospitality industry, almost singlehandedly sending the hotel sector into oversupply and denting room rates in the process, regulators have sought to strike back and disrupt Airbnb. In October 2016, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed legislation that raised fines for New Yorkers caught illegally listing short-term rentals online; cities like Miami have taken similar measures, and New Jersey is said to be vetting its own regulations.

The hotel industry has played an influential role in pushing lawmakers to pass such measures, as The New York Times reported in April. Airbnb, however, has pushed back, filing a countersuit immediately after Cuomo signed the New York bill into law and succeeding in obtaining a restraining order blocking Miami’s attempt to ban short-term rentals. But it appears all the pressure has had some negative impact on Airbnb’s business, with the company’s growth slowing in recent months, according to an analysis by UBS.

Still, Airbnb turned a profit for the first time in the second half of 2016 and expects to remain profitable in 2017. This March, it raised $1 billion in its latest funding round—a haul that valued the company at a remarkable $31 billion. That same month, Chief Executive Officer Brian Chesky said Airbnb is “halfway through the two-year process of getting ready to go public”—with a 2018 initial public offering now looking likely.

Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey, WeWork

While coworking outfits like Regus have been around for decades, WeWork is now essentially synonymous with the office-sharing phenomenon it helped popularize. In the seven years since its founding, the company has swollen into a business valued at $17 billion, with more than 170 locations in over 40 cities around the world.

Simultaneously, WeWork has gobbled up tens of millions of square feet of office space, changing the complexion of major office markets and epitomizing how the modern workplace must evolve to serve today’s workforce. WeWork offices are spacious, comfortable, open, distinct in their design and highly amenitized; every office landlord and broker in the world now knows how important these traits are in drawing the creative, tech- and information-oriented companies—often staffed and helmed by millennials—that are increasingly driving the economy.

As such, WeWork is now looking to bring its services to companies larger than the small- to medium-sized firms that embody the coworking model. Through its recently launched “Enterprise” division, WeWork is now offering full-floor spaces and even entire locations to single tenants, while also outsourcing its services to construct, design and manage existing office spaces occupied by clients.

So after threatening to completely overhaul the traditional office leasing and design model, WeWork is now looking to give traditional commercial property managers, designers and interior architects a run for their money on their own turf.

Ross Bailey, Appear Here

After taking London and Paris by storm, Appear Here—“Tinder for shops,” according to its founder and CEO, Ross Bailey—launched in New York City this year. Using an online platform featuring a database of 80,000 brands in the market for short-term retail space, landlords like Blackstone Group, Brookfield Property Partners and Thor Equities are able to book tenants at their properties across Manhattan and Brooklyn in just a fraction of the time typically associated with negotiating a retail lease.

Much as Airbnb disrupted the hotel space, Appear Here hopes to shake up the traditional retail brokerage model. The company—which Bailey founded in 2013 at the age of 20—claims that most of the leases booked on its platform are signed and sealed in three to six days. That undoubtedly has much to do with its short-term leasing model: Appear Here only deals in retail leases ranging from pop-ups that are open for a few days up to two-year agreements.

But Bailey says that model is merely a response to how “the current model of retail is dying,” with tenants—in the worst brick-and-mortar retail economy in years—realizing that long-term leases (the traditional five- to 15-year model) don’t always make sense. “I don’t see us as taking business away from [brokers],” Bailey recently told CO. “I see us as bringing something that never existed before to the market.”